Read The Grand Turk: Sultan Mehmet II - Conqueror of Constantinople and Master of an Empire Online

Authors: John Freely

Tags: #History, #Biography

The Grand Turk: Sultan Mehmet II - Conqueror of Constantinople and Master of an Empire (2 page)

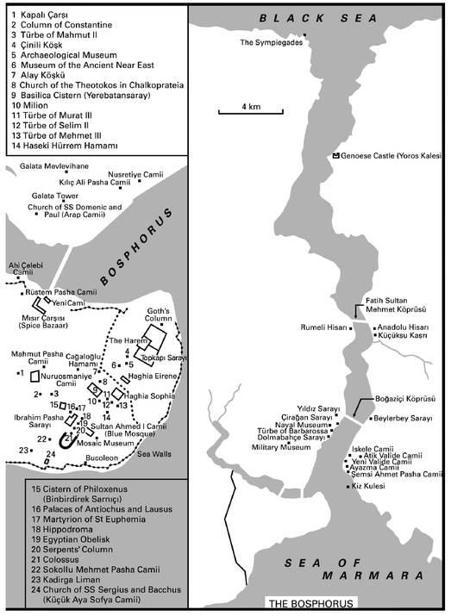

Istanbul and the Bosphorus

1

The Sons of Osman

Constantine the G reat changed the course of history in AD 330, when he shifted his capital from Italy to the Greek city of Byzantium on the Bosphorus, renaming it New Rome, though it came to be called Constantinople.

Constantine’s immediate successors established Christianity as the state religion of the empire, and during the next two centuries Greek replaced Latin as the official language. This gave rise to what later historians called the Byzantine Empire, the Hellenised Christian continuation of the Roman Empire, which took its name from the ancient city of Byzantium.

The Byzantine Empire reached its peak under Justinian (r. 527-65), whose realm extended almost entirely around the Mediterranean, including all of Italy, the Balkans, Asia Minor and the Middle East. During the next five centuries the empire was under attack on all sides, but as late as the mid-eleventh century it still controlled all of Asia Minor and the Balkans as well as southern Italy. But then in 1071 the emperor Romanus IV Diogenes was defeated by the Seljuk Turks under Sultan Alp Arslan at a battle near Manzikert in eastern Anatolia, as Asia Minor is now more generally known, while that same year the Normans took the last remaining Byzantine possessions in Italy.

After their victory at Manzikert the Turks overran Anatolia, though the Byzantines, with the help of the army of the First Crusade, reconquered the western part of Asia Minor and the coastal areas along the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. The central and eastern parts of Anatolia became part of the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum, the Turkish word for Greeks of the Byzantine Empire, whose territory they had conquered.

The Seljuk Sultanate of Rum lasted from the second half of the eleventh century until the beginning of the fourteenth century. At their peak, in the first quarter of the thirteenth century, the Seljuks controlled all of Anatolia except for Bithynia, the north-westernmost part of Asia Minor, which was virtually all that remained of the Byzantine Empire in Asia, while the Greek empire of the Comneni dynasty ruled the eastern Black Sea region from their capital at Trebizond.

The Byzantine Empire was almost destroyed during the Fourth Crusade, when Latin troops and the Venetian navy captured and sacked Constantinople in 1204. Constantinople then became capital of a Latin kingdom called Roumania, which lasted until 1261, when the city was recaptured by the Greeks under Michael VIII Palaeologus, who had survived in exile in the Bithynian city of Nicaea.

But the revived Byzantine Empire was just a small fragment of what it had been in its prime, and by the beginning of the fifteenth century it comprised little more than Bithynia, part of the Peloponnesos, and Thrace, the south-easternmost region of the Balkans up to the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus, the historic straits that separate Europe and Asia.

The Seljuks declined rapidly after they were defeated by the Mongols in 1246, and at the beginning of the following century their sultanate came to an end, with their former territory divided among a dozen or so Turkish emirates known as

beyliks

. The smallest and least significant of these

beyliks

was that of the Osmanlı, the ‘sons of Osman’, the Turkish name for the followers of Osman Gazi, whose last name means ‘warrior for the Islamic faith’. Osman was known in English as Othman, and his dynasty came to be called the Ottomans. He was the son of Ertuğrul, leader of a tribe of Oğuz Turks who at the end of the thirteenth century settled as vassals of the Seljuk sultan around Söğüt, a small town in the hills of Bithynia, just east of the Byzantine cities of Nicomedia, Nicaea and Prusa. The humble origin of the Osmanlι is described by Richard Knolles in

The Generall Historie of the Turkes

(1609-10), one of the first works in English on the Ottomans:

Thus is Ertogrul, the Oguzian Turk, with his homely heardsmen, become a petty lord of a countrey village, and in good favour with the Sultan, whose followers, as sturdy heardsmen with their families, lived in Winter with him in Söğüt, but in Summer in tents with their cattle upon the mountains. Having thus lived certain yeares, and brought great peace with his neighbours, as well the Christians as the Turks… Ertogrul kept himself close in his house in Söğüt, as well contented there as with a kingdom.

The only contemporary Byzantine reference to Osman Gazi is by the chronicler George Pachymeres. According to Pachymeres, the emperor Andronicus II Palaeologus (r. 1282-1328) sent a detachment of 2,000 men under a commander named Muzalon to drive back a force of 5,000 Turkish warriors under Osman (whom he calls Atman), who had encroached upon Byzantine territory. But Osman forced Muzalon to retreat, which attracted other Turkish warriors to join up with him, in the spirit of

gaza

, or holy war against the infidel, attracted also by the prospects of plunder.

With these reinforcements Osman defeated Muzalon in 1302 in a pitched battle at Baphaeus, near Nicomedia. Soon afterwards Osman captured the Byzantine town of Belakoma, Turkish Bilecik, after which he laid siege to Nicaea, whose defence walls were the most formidable fortifications in Bithynia. He then went on to pillage the surrounding countryside, causing a mass exodus of rural Greeks from Bithynia to Constantinople, after which he captured a number of unfortified towns in the region.

Osman Gazi died in 1324 and was succeeded by his son Orhan Gazi, the first Ottoman ruler to use the title of sultan, as he is referred to in an inscription. Two years after his succession Orhan captured Prusa, Turkish Bursa, which became the first Ottoman capital. He then renewed the siege of Nicaea, and in 1329 the emperor Andronicus III Palaeologus (r. 1328-41) personally led an expedition to relieve the city. Orhan routed the Byzantine army at the Battle of Pelekanon, in which the emperor was wounded, leaving his commander John Cantacuzenus to lead the defeated army back to Constantinople.

Nicaea, known to the Turks as Iznik, was finally forced to surrender in 1331, after which Orhan went on to besiege Nicomedia, Turkish Izmit, which finally surrendered six years later. That virtually completed the Ottoman conquest of Bithynia, by which time Orhan had also absorbed the neighbouring Karası

beylik

to the south, so that the Ottomans now controlled all of westernmost Anatolia east of the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles.

Andronicus III died on 15 June 1341 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son John V Palaeologus. John Cantacuzenus was appointed regent, and later that year his supporters proclaimed him emperor. This began a civil war that lasted until 8 February 1347, when Cantacuzenus was crowned as John VI, ruling as senior co-emperor with John V.

Meanwhile, Orhan had signed a peace treaty in 1346 with Cantacuzenus. Cantacuzenus sealed the treaty by giving his daughter Theodora in marriage to Orhan, who wed the princess in a festive ceremony at Selymbria, in Thrace on the European shore of the Marmara forty miles west of Constantinople. Shortly after Cantacuzenus was crowned as senior co-emperor in 1347 Orhan came to meet him at Scutari, on the Asian shore of the Bosphorus opposite Constantinople. According to the chronicle that Cantacuzenus later wrote, he and his entourage crossed the Bosphorus in galleys to meet Orhan and his attendants, ‘and the two amused themselves for a number of days hunting and feasting’.

Cantacuzenus ruled as co-emperor until 10 December 1354, when he was deposed by the supporters of John V, after which he retired as a monk and wrote his chronicle, the

Historia

, one of the most important sources for the last century of Byzantine history and the rise of the Ottoman Turks.

Throughout his reign Cantacuzenus honoured the alliance he had made with Orhan. During that time Orhan thrice sent his son Süleyman with Turkish troops to aid Cantacuzenus on campaigns in Thrace. On the third of these campaigns, in 1352, Süleyman occupied a fortress on the Dardanelles called Tzympe, which he refused to return until Cantacuzenus promised to pay him 1,000 gold pieces. The emperor paid the money and Süleyman prepared to return the fortress to him, but then, on 2 March 1354, the situation changed when an earthquake destroyed the walls of Gallipoli and other towns on the European shore of the Dardanelles, which were abandoned by their Greek inhabitants. Süleyman took advantage of the disaster to occupy the towns with his troops, restoring the walls of Gallipoli in the process. A Florentine account of the earthquake and its aftermath says that the Turks then ‘received a great army of their people and laid siege to Constantinople’, but after they were unable to capture it ‘they attacked the towns and pillaged the countryside’. Cantacuzenus demanded that Gallipoli and the other towns be returned, but Süleyman insisted that he had not conquered them by force but simply occupied their abandoned ruins. Thus the Ottomans established their first permanent foothold in Europe, which Orhan was able to use as a base to make further conquests in Thrace.

Orhan also extended his territory eastward in Anatolia, as evidenced by a note in the

Historia of Cantacuzenus

, saying that in the summer of 1354 Süleyman captured Ancyra (Ankara), which had belonged to the Eretnid

beylik

, thus adding to the Ottoman realm a city destined to be the capital of the modern Republic of Turkey.

A Turkish source says that Süleyman captured the Thracian towns of Malkara, Ipsala and Vize. This would have been prior to the summer of 1357, when Süleyman was killed when he was thrown from his horse while hunting.

Orhan Gazi died in 1362 and was succeeded by his son Murat, who had been campaigning in Thrace. In 1369 Murat captured the Byzantine city of Adrianople, which as Edirne soon became the Ottoman capital, replacing Bursa. Murat used Edirne as a base to campaign ever deeper into the Balkans, and during the next two decades his raids took him into Greece, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Albania, Serbia, Bosnia and Wallachia. On 26 September 1371 Murat annihilated a Serbian army at the Battle of the Maritza, opening up the Balkans to the advancing Ottomans. By 1376 Bulgaria recognised Ottoman suzerainty, although twelve years later they tried to shed their vassal ties, only provoking a major Turkish attack that cost them more territory.

At the same time, Murat’s forces expanded the Ottoman domains eastward and southward into Anatolia, conquering the Germiyan, Hamidid and Teke

beyliks

, the latter conquest including the Mediterranean port of Antalya.

Murat’s army occupied Thessalonica in 1387 after a four-year siege, by which time the Ottomans controlled all of southern Macedonia. His capture of Niš in 1385 brought him into conflict with Prince Lazar of Serbia, who organised a Serbian-Kosovan-Bosnian alliance against the Turks. Four years later Murat again invaded Serbia, opposed by Lazar and his allies, who included King Trvtko I of Bosnia.

The two armies clashed on 15 June 1389 near Pristina at Kosovo Polje, the ‘Field of Blackbirds’, where in a four-hour battle the Turks were victorious over the Christian allies. At the climax of the battle Murat was killed by a Serbian nobleman who had feigned surrender. Lazar was captured and beheaded by Murat’s son Beyazit, who then slaughtered all the other Christian captives, including most of the noblemen of Serbia. Serbia never recovered from the catastrophe, and thenceforth it became a vassal of the Ottomans, who were now firmly established in the Balkans.

Soon afterwards Beyazit murdered his own brother Yakup to succeed to the throne, the first instance of fratricide in Ottoman history. Beyazit came to be known as Yıldırım, or Lightning, from the speed with which he moved his army, campaigning both in Europe and Asia, where he extended his domains deep into Anatolia.

Beyazit’s army included an elite infantry corps called

yeniçeri

, meaning ‘new force’, which in the West came to be known as the janissaries. This corps had first been formed by Sultan Murat from prisoners of war taken in his Balkan campaigns. Beyazit institutionalised the janissary corps by a periodic levy of Christian youths called the

devşirme

, first in the Balkans and later in Anatolia as well. Those taken in the

devşirme

were forced to convert to Islam and then trained for service in the military, the most talented rising to the highest ranks in the army and the Ottoman administration, including that of grand vezir, the sultan’s first minister. They were trained to be loyal only to the sultan, and since they were not allowed to marry they had no private lives outside the janissary corps. Thus they developed an intense esprit de corps, and were by far the most effective unit in the Ottoman armed forces.