The Good and Evil Serpent (99 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

The Possible Remnants of a Synagogal Sermon

. The preceding reflections indicate that in Greece, Italy, Syria, Egypt, India, Mesopotamia, indeed in all known cultures, the serpent was revered as a positive symbol. An objection might be raised; some might claim that while Jews in Palestine and Syria admired the serpent, they never would have depicted it anywhere near a synagogue. That is now proved to be another false presupposition.

The serpent is clearly shown iconographically in synagogues from southern to northern Roman Palestine. From the fifth-century synagogue at Gaza, once incorrectly identified as a church, comes a mosaic depicting David. An upraised serpent, along with a lion cub and a giraffe, is depicted listening to David, as Orpheus, playing a lyre.

160

Moving from the southwest to the northeast of Roman Palestine, we come to a serpent elegantly chiseled on a beam above a Hebrew inscription. It is not from a so-called pagan temple; it is from the Golan and the late fifth-century

CE

synagogue at

c

En Neshut.

161

Moreover, the serpent is formed to represent a Hercules knot.

162

Also from the Golan, and this time from the village at Dabbura, and probably from a synagogue that dates from the early fifth century, is found a lintel with two eagles—each of them holding a serpent. Between the two eagles, and above the long serpent, is a Hebrew inscription: “This is the academy of the Rabbi Eliezar ha-Qappar.”

163

Not only does this lintel take us back to the second century

CE

, but a serpent is depicted above the academy of a rabbi known to be famous according to the Mishnah and Talmudim (e.g.,

t. Betzah

1.7;

j. Ber

. 1.3).

164

While the image of the serpent is now clearly shown to be part of the synagogue, and also of rabbinic academies, I would think it likely that some Jews depicted the serpent in light of mythological ideologies.

165

The serpent is associated not only with Orpheus but also with a Herculean knot; even still, the general absence of “pagan” iconography lifts the serpent out of mythology into the religious symbolic world of Judaism, both before and after 70

CE

(when the Temple was burned and the nation destroyed).

Within this cultural setting for early rabbinic teaching and worship, I am persuaded that it is conceivable that the Fourth Evangelist had been influenced by a synagogal sermon he had heard—or even delivered—based on an exegesis of Numbers 21:8–9. He probably inherited the serpent symbolism from the Son of Man sayings, which he obtained from traditions known to the Johannine school or circle.

166

The Fourth Evangelist is not dependent only on a so-called Christian exegetical and hermeneutical use of Numbers 21, as Bultmann claimed.

167

He may have known the Jewish traditions that shaped the Christological interpretation of Numbers 21 by the author of

Barnabas

(12) and Justin Martyr

(1 Apol

. 60 and

Dial

. 91, 94, and 112). These authors inherited traditions that are clearly Jewish.

168

The importance of Numbers 21, as we have seen, was developed by the author of the Wisdom of Solomon and later Jewish sources (esp.

m. Rosh Hash

. 3 and

Mekilta to Exod

17:11).

Six observations have led me to the conclusion that the Fourth Evangelist was influenced by a synagogal sermon when he composed 3:14. These may now be mentioned only briefly:

1. The Fourth Gospel is very Jewish, and is shaped by the celebration of the Jewish festivals in synagogues after 70.

2. The members of the Johannine community desired to attend synagogal services.

3. Philo of Alexandria based two homilies on Numbers 21:8–9. He stresses, under the influence of the Septuagint, that “the serpent” is “the most subtle [ ] of all the beasts”

] of all the beasts”

(Leg

. 2.53). In

Legum al-legoriae

2.76–79, Philo claims that Moses’ uplifted serpent symbolized “self-mastery” or “prudence” ( ) (cf. Pos. 6), which is a possession only of those beloved by God or God-lovers (

) (cf. Pos. 6), which is a possession only of those beloved by God or God-lovers ( ). In

). In

De agricultura

94–98, Philo centers again on serpent symbolism to assist his allegorical interpretations of Scripture. Philo perceives the serpent to be of “great intelligence,” and able to defend itself “against wrongful aggression.” Eve’s serpent is an allegory of lust and pleasure (cf. Neg. 6), but Moses’ serpent represented protection from death and self-control (cf. Pos. 6).

169

The serpent also symbolizes “steadfast endurance,” and that is why Moses made the serpent from bronze. The serpent of Moses also symbolizes life; the one who looked on with “patient endurance,” though bitten by “the wiles of pleasure, cannot but live” (98 [cf. Pos. 20, 26, 27]).

170

4. The importance of Numbers 21:8–9 would be familiar to all early Jews who knew the Wisdom of Solomon 16:6–7, 13. Noteworthy are especially the interpretations that “the one who turned toward it [not the serpent but “the commandment of your Law”] was saved,” and that God alone is “Savior of all.”

171

5. The Johannine emphasis of being from above—stressed in Jesus’ conversation with Nicodemus—is the theme that leads to and frames 3:13–15. It is the same exegetical meaning brought out of Numbers 21:8–9 according to the Mishnah; that is, the Israelite must remain faithful, direct thoughts to heaven above, and remain in subjection to the Father. After quoting Numbers 21:8,

Rosh Hashanah

has this ethical advice

(halacha):

“But could the serpent slay or the serpent keep alive!—it is, rather, to teach thee that such time as the Israelites directed their thoughts

on high

and kept their hearts in subjection

to their Father in heaven

, they were healed; otherwise they pined away” (3:8 [italics mine]).

172

J. Neusner presents the following translation: “But: So long as the Israelites would set their eyes upward and submit to their Father in heaven, they would be healed.”

173

Some readers might even be forgiven for imagining, before reflection, that

Rosh Hashanah

has a Johannine ring to it.

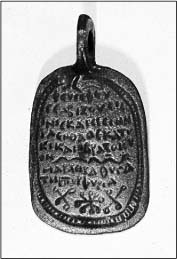

Figure 83

. Gnostic Amulet. Roman Period. Jerusalem? JHC Collection

6. The Targum interprets Numbers 21 to denote that believers are to turn their heart toward the

Memra

of God (i.e., the divine Word of God).

174

Do portions of John 3:13–15 derive from a synagogal sermon? For me, this question remains unanswered yet intriguing. It is likely, as many scholars have concluded (viz. M. E. Boismard and A. Lamouille), that John 3:14 develops from an old Jewish tradition that has been expanded by the Fourth Evangelist.

175

I am now more interested in the possible evidence of ophidian symbolism and perhaps ophidian Christology (which was distorted by the Ophites) left elsewhere in the Fourth Gospel. It seems to me that serpent imagery is not a central concern of the Fourth Evangelist, but it may have been of keen interest to some in his circle (especially all the former devotees of Asclepius).

An Underlying Ophidian Christology in the Gospel of John?

It is now virtually certain that the serpent served as a typology of Jesus for the Fourth Evangelist, and it is imperative to recall that, before the Fourth Evangelist, Moses’ serpent was a symbol of salvation. According to the author of the Wisdom of Solomon 16:6, Moses’ serpent was “a symbol of salvation” ( ). As M.-J. Lagrange stated in 1927: “Jesus shall be reality” (“Jésus sera la réalité”)—that is, Jesus is salvation.

). As M.-J. Lagrange stated in 1927: “Jesus shall be reality” (“Jésus sera la réalité”)—that is, Jesus is salvation.

176

Now, we can ask to what extent the Evangelist left traces of an incipient ophidian Christology in the Fourth Gospel. While I am uneasy about clarifying what an ancient author might have meant by a symbol, I am convinced that the Fourth Evangelist thought things out along the lines already explained. The penchant of denying such thoughts to the Evangelist also seems unwise when one realizes that the Fourth Gospel reflects a living history. The Evangelist and others in the Johannine school reshaped and edited the gospel over forty years. The text was most likely discussed in the Johannine school, and concepts latent in the text might have become clearer to the Evangelist through his own study of the text or through discussions with others.

If the Evangelist did not think about some passages in the Fourth Gospel as mirroring serpent symbology, it would be rash to claim that none of his readers would be blind to what seems clear, after exploring the labyrinth of meanings attributed to the serpent by the ancient thinkers. Not only audience criticism and reader-response criticism but also narrative criticism allows us to ask to what extent the Evangelist or his readers might have seen the serpent, the symbol of life (Pos. 20) and immortality (Pos. 27), mirrored in chapters subsequent to John 3:14.