The Good and Evil Serpent (102 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

The poetic structure of 3:14–15 is synonymous

parallelismus membro-rum

. The serpent in stichos one is parallel to the Son of Man, Jesus, in stichos two.

The grammar of 3:14 points to the identity of the Son of Man as the serpent; only “serpent” and “Son of Man” are placed in the accusative case and aligned. John 3:15 has one noun in the accusative case: “eternal life.” Thus, the thought moves from “serpent” to “Son of Man” and then to “eternal life.” Looking up to the Son of Man and believing in him reveal the continuing influence of Numbers 21 and the life-giving serpent who symbolizes eternal life. The influence of ophidian symbology becomes clear: The serpent symbolizes life and immortality (Pos. 20 and 27).

A study of ophidian symbology in antiquity clarifies, sometimes for the first time, some major dimensions of the theology and Christology of the Fourth Gospel. To summarize:

1. Jesus is the Son of Man who is like the upraised serpent that gives life to those who look up to him and believe. The Fourth Evangelist describes Jesus’ crucifixion so that only his mother and the Beloved Disciple are narratively described looking up to Jesus on the cross (19:26–27, 35).

The serpent raised up by Moses is a typology of the Son of Man, Christ. The history of salvation does not begin at the baptism. As the Fourth Evangelist made clear in the Prologue to his Gospel, it began “in the beginning.” That is, Jesus’ life must be understood from the perspective of God’s actions in history and foreshadowing in Scripture, especially Genesis 1:1, “In the beginning …”

2. As God gave life to those who looked up to the serpent and believed God’s promise, so Jesus gives life to all who look up to him and believe in him. By looking up to Jesus, lifted up on the cross, one is looking not only at an antitype—the upraised serpent, the crucified Jesus. One is looking up to heaven—the world above. It is from there that the Johannine Jesus has come and is returning. He, the Son of Man, alone descended to earth (3:13) to prepare a place for those who follow him. In the words of conservative Old Testament scholar R. K. Harrison: “In the same way that the ancient Israelite was required to look in faith at the bronze serpent to be saved from death, so the modern sinner must also look in faith at the crucified Christ to receive the healing of the new birth (Jn 3:14–16).”

199

3. Trust or believing is required so that God through the serpent and Jesus can provide life to all who look up to the means of healing and new life, including eternal life. No other New Testament author employs the verb “to believe” as frequently and deeply as the Fourth Evangelist. He chooses it, and accentuates it pervasively, and he indicates the dynamic quality of “believing” by avoiding the noun “faith.”

4. The paradigmatic importance of “up” and “above,” so significant for Johannine Christology, is heightened by a recognition that Jesus represents the serpent raised up above the earth. It helps us understand the double entendre Jesus is making while talking with Nicodemus. Jesus tells Nicodemus he must be born

anothen

, which is a wordplay denoting both “again,” and “above.”

5. The serpent was chosen symbolically to indicate healing in the cult of Asclepius. The same symbol was used in Jewish groups contemporaneous with the Fourth Gospel. Later “Jews” and “Christians” created and employed amulets that depict the powers of Yahweh with serpent feet or other features taken from serpent iconography. Ophidian symbolism and iconography help us comprehend why the Fourth Evangelist indicates that Jesus, as the serpent, provides healing for all who turn to him.

6. We have seen ample evidence that the serpent is a symbol of immortality or resurrection in many segments of the culture in which the Fourth Gospel took shape. This dimension of serpent symbolism may be seen as undergirding the thought expressed by the Fourth Evangelist. Indeed, the Fourth Gospel appears to be a blurred mirror in which we see reflected discussions on this topic in the Johannine community, school, or circle.

Figure 84

. Jewish-Gnostic Amulet Showing Lion, Stork, Scorpion, Serpent, and Ram [?]. Greek inscription: IAW (= Yahweh, God’s name in Hebrew), Sabao (Sabaoth), Michael. Third-fifth centuries CE. Jerusalem? JHC Collection

7. Finally, Numbers 21:8–9 is a text used intertextually by the Fourth Evangelist. It helps shape his narrative and enables him to present the profundity of his Christology. We have also seen that Moses’ upraised serpent was a subject of interest for many Jews (viz. in Wis 16, Philo’s

Leg

. 2 and

Agr

. 94). A study of the Fourth Gospel needs to be informed by such Jewish exegesis of Genesis 3 and Numbers 21. In light of such traditions, it becomes clearer how and why the Fourth Evangelist perceived Jesus’ crucifixion. The crucifixion was not a failure; it was a necessity and mirrors Jesus’ exaltation and return to the world above.

8. The Fourth Evangelist shapes his thoughts and symbols by the use of the light–darkness paradigm. Johannine thought is enriched by the recognition that the serpent god is depicted as controlling light and darkness. According to an excerpt that Philo of Byblos derived from a “sacred scribe,” when the serpent opened his eyes, “there was light” and when he shut his eyes “there was darkness.”

200

For those in the Johannine community who were deeply influenced by the power of serpent symbolism, this allegorical imagery would help them understand a key passage: “I am the light of the world” (8:12; cf. 3:19, 12:35–36).

201

There should be no doubt that some who read the Fourth Gospel in antiquity would have seen Jesus in light of serpent symbolism. Both symbolized light (Pos. 3 and 7).

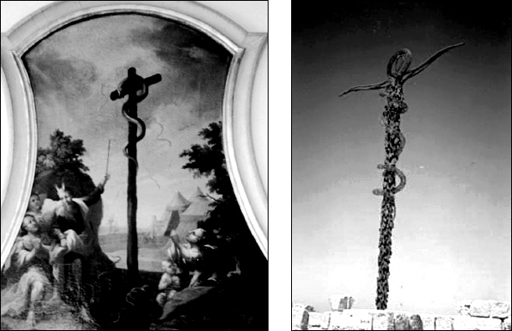

Figure 85

.

Left

. Serpent on Cross. Picture, “St Virgil,” in the Bildunghaus in Salzburg. Courtesy of Professor P. Hofrichter.

Figure 86

.

Right

. Serpent on Cross. Mount Nebo. Modern. JHC

As we have already seen when studying Genesis 3, artists often serve as more perceptive biblical exegetes than biblical scholars. That is because they must live in the scene and story depicted, imagine all descriptions, and then transpose the prose and poetry into art.

Artists sometimes depict Jesus as a serpent on a cross. Two examples must suffice. One is in a painting in a church in Salzburg. The cross is clear, as is the serpent who symbolizes Jesus. On Mount Nebo today, Numbers 21 conflates with John 3. Not a stake but a cross is artistically depicted. The one on it is clearly a serpent who represents Jesus.

The Warburg Institute in London has collected many symbolic representations of the Son of Man (Jesus) as the serpent, according to John 3:14. Two examples may now be chosen to make the point that artists, under the influence of John 3:14, often see Jesus as a serpent on the cross. In his

S. Ioannes

, Jacques Callot (1592–1635) depicted a person kneeling and praying beside a small staff on which a serpent is entwined; a large tree is above both. Wolf Huber, also named Barthel Beham (1502–40), portrayed Jesus on the cross and to the left of him is the serpent on the pole.

202

Other examples may be mentioned, but I shall limit my presentation to just three.

203

First, a lead sarcophagus in Jerusalem, from the early Christian period, shows a cross with serpent feet. The imagery most likely derives from imaginative reflections on John 3:14. Second, the upper part of a gravestone, found perhaps in Luxor in 1906, contains a cross under which are two serpents with heads uplifted.

204

Third, a pottery figure from Drenthe in the Netherlands shows a large serpent coiling upward and around a cross or outstretched arms. As Leclercq concluded, most likely the figure represents the serpent of the wilderness as a symbol of Christ.

205

The ceramic figure thus was an interpretation of John 3:14 that equated “the Son of Man” with the serpent that Moses lifted up in the wilderness.

Figure 87

.

Mater Auxiliatrix

. Naples. JHC

The painting in

Fig. 87

focuses the viewer’s attention on Jesus with Mary, a saint, and, most important, centered between them a cup with two upraised serpents. What does this picture symbolize? Is it possible that a gifted artist has created a scene that is based on an insightful interpretation of John 3:14–16? If so, this meaning has been lost for those who have studied it, as I learned talking with a priest who published a work devoted to it. The colorful painting seems to mystify those who focus on it. In order to perceive the in-depth meaning of this painting, I have divided the following presentation into facts, opinions, and my own explanation.

Facts

. The painting has been moved many times. It was originally in the convent of Santa Maria di Casarlano, a village that is presently incorporated within Sorrento. The impressive painting is now in a chapel, Cappella del Noviziato, on an upper floor within Gesù Nuovo, the Jesuit residence in downtown Naples. The date of composition and the artist are unknown. Thus, any basis for interpretation cannot appeal to date or creator. What is the meaning of this picture? What do the two serpents symbolize?

Opinions

. Some priests in Naples told me that the painting may have been composed to celebrate the founding of the convent, Santa Maria di Casarlano. If so, then the work would have been created about 1496. I asked a Jesuit who had studied the painting what the meaning of the two serpents was. He was drawn primarily to the dominant figure of the Virgin Mary, and admitted that, perhaps, the serpents represented some heresy. He confessed that he did not know.

My Interpretation

. The painting has been moved because of embarrassment. Many consider the images of serpents in a cup to be heretical.

The painting is probably not connected with the founding of the convent.

206

It is later than the fifteenth century. It did exist in the sixteenth century because the Turks—who sought to desecrate a celebration of Christian symbols—shoved their swords and knives into it in 1558.

207

Its style seems to connect the painting with the school of Giotto. One may surmise that the painting dates from the middle of the sixteenth century.

208

Why is the painting impressive? Most viewers have been drawn to it because of the beatific view of the Virgin Mary. She is the dominant figure, situated in the middle and elevated above the males on her right and left. She is feminine and attractive, especially as she leans her cheek adoringly on the head of the Christ child. One can appreciate why the “Madonna di Casarlano” is revered “come

Auxilium Christianorum”

or, more affectionately,

“Mater Auxiliatrix.”

209