The Good and Evil Serpent (92 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

Quite significantly, the noun “Savior” appears more than once in this passage; that is because both figures, Asclepius and Christ, were proclaimed to be the Savior. While it is possible that the prior use of “Savior” by the devotees of Asclepius influenced Christology, it is clear that the two “Roman cults” clashed. Both could not be the only Savior of the world.

Even Clement of Alexandria, who has some harsh things to report about Asclepius, recorded the claim that “the Phoenicians and the Syrians first invented letters; and that Apis, an aboriginal inhabitant of Egypt, invented the healing art before Io came into Egypt. But afterwards they say that Asclepius improved the art.”

59

A vast number of Greeks and Romans agreed with Pindar that Asclepius was the “gentle craftsman who drove pain from the limbs that he healed,—that hero who gave aid in all manner of maladies.”

60

Tertullian’s comments mirror the threat of the Asclepiads to Christians; in his judgment they were all demons. Note his words:

Let that same Virgin Caelestis herself the rain-promiser, let Aesculapius discoverer of medicines, ready to prolong the life of Socordius, and Tenatius, and Asclepiodotus, now in the last extremity, if they would not confess, in their fear of lying to a Christian, that they were demons, then and there shed the blood of that most impudent follower of Christ.

61

This confusing excerpt is chosen to make only one point. The words of Tertullian mirror the threat of Asclepius (Aesculapius) for Christ; the former seems merely to be an “impudent follower of Christ.” In

The Chap-let

, Tertullian rejects the claim that Asclepius was “the first who sought and discovered cures.” Tertullian claims that much earlier “Esaias [Isaiah] mentions that he ordered Hezekiah medicine when he was sick. Paul, too, knows that a little wine does the stomach good.”

62

Origen knew the claims that Jesus’ death was similar to Asclepius’ death. He rejects such claims and similarities between the two most famous miracle workers before the time of the Fourth Evangelist. Note Ori-gen’s words:

But we, in proving the facts related of our Jesus from the prophetic Scriptures, and comparing afterwards His history with them, demonstrate that no dissoluteness on His part is recorded. For even they who conspired against Him, and who sought false witnesses to aid them, did not find even any plausible grounds for advancing a false charge against Him, so as to accuse Him of licentiousness; but His death was indeed the result of a conspiracy, and bore no resemblance to the death of Aesculapius by lightning.

63

The threat to Jesus’ followers from the devotees of Asclepius resulted not only from the popularity of the Asclepian cult but also because Asclepius’ life was virtually a mirror of the story of Jesus. Asclepius was originally perceived as a human. In Homer and other early authors, Asclepius is a human. He is the great physician. He dies, and appears again in dreams, and, according to some of his devotees, he is alive again. He becomes a god equal to Zeus, an elevation that seems to have taken place during the time when the Fourth Gospel was being composed and edited.

64

Note these reflections by Justin Martyr: In what was it possible for Jesus Christ to make “whole the lame, the paralytic, and those born blind, we seem to say what is very similar to the deeds said to have been done by Aesculapius.”

65

The similarities between the story of Asclepius and the gospel about Jesus are thus undeniable. The followers of Jesus were challenged not only by the Asclepiads and their devotion to Asclepius, but also by the story of Asclepius and his promise of health and everlasting life.

66

Two of the most significant works on Christ and Asclepius were published in the 1980s. In 1980, E. Dinkler focused on the Christ typology reflected in a polychromatic scene of a meal and healings. This scene is found in high relief on a broken plaque in the Mesa National Romano.

67

He points out that the sculpture seems to depict Christ in light of Asclepius. The second is a 1986 Harvard University dissertation by R. J. Riittimann: “The Form, Character and Status of the Asclepius Cult in the Second Century CE and Its Influence on Early Christianity.”

Rüttiman has missed two of the major publications on Asclepius and Jesus. He seems not to know about Dinkler’s publication, which appeared eight years earlier. He does know and benefit from a major study by K. H. Rengstorf that is devoted to the beginnings of the clash between Christians and devotees of Asclepius.

68

While Rengstorf dates the beginnings of this sociological and religious confrontation to the middle of the second century

CE

, there are reasons to assume it may already be present earlier.

We have obtained some insight into why the serpent was not a positive symbol for most early Christians. Those with whom Christians were struggling to survive and develop a normative self-understanding had appropriated the positive symbol of the serpent. It would have made an appropriate symbol, however, in light of Numbers 21 and John 3.

In the following pages we shall ask the questions allegedly already asked and answered if Johannine experts have concluded that Jesus cannot be parallel to the serpent in John 3:14. Are comparisons between Jesus and the serpent “misplaced”? Does the analogy in John 3 apply “only to being lifted up”?

What is the “classic typology” to which D. M. Smith refers? How can the typology be only to lifting up? Was it not important to the Fourth Evangelist that it was necessary

for Jesus

to be lifted up? Does not John 3:14–15 also include the full typology: Moses’ serpent placed on a pole represents Jesus’ “exaltation” on the cross? In John 12:32–33, the Fourth Evangelist makes it clear that to lift up refers to Jesus’ crucifixion; is only crucifixion intended in John 3:14–15?

Is Smith correct to report that “comparisons of Jesus with the serpent are misplaced; the analogy applies only to being lifted up”?

69

How could the Evangelist think only about lifting up and never about the lifting up of Jesus? Are such comparisons misplaced, if Jesus is then portrayed to be the one who brings life abundantly, a key attribute of serpent symbology?

The interpretation of John 3:14 entails searching for the meaning of a symbol: the serpent. Four components are involved: the symbol maker (the Fourth Evangelist), the symbol, the meaning of the symbol, and the interpreter of the symbol (in antiquity and today). Clearly, the central concern for us is the third component part: the meaning of a symbol. Does it reveal or point toward meaning? We shall see that both are involved, especially the latter.

To establish the point that the Fourth Evangelist thinks about Jesus as Moses’ serpent, and to forge against the stream of Johannine research, we need to demonstrate nine points:

- The serpent was a powerful and positive symbol in the culture of the Fourth Evangelist.

- The grammar of John 3:14 indicates some relation between Jesus and the serpent.

- The syntax indicates that Jesus and the serpent are related.

- The poetry of the passage draws a parallel between the serpent and Jesus.

- The Son of Man traditions employed in this verse, John 3:14, are ancient and already rich with Christological overtones that would accommodate serpent imagery and symbolism.

- The key symbols in Johannine theology support the insight that Jesus is seen in John 3 as a mirror reflection of Moses’ serpent on the pole. Both demand commitment or belief and both promise “life.” This is the dominant symbolic meaning of the serpent in the first century

CE;

for example, the Asclepiads claimed that Asclepius could heal and bring new life—and he was symbolized as the serpent in dreams and with shown with a serpent on his staff in paintings and sculptures. - Intertextuality.

- The possible remnants of a synagogal sermon.

- The evidence of an underlying anguine Christology in the Gospel of John.

70

These explorations will help clarify to what extent the Fourth Evangelist imagined Jesus as a type of Moses’ serpent as well as confirm that ophidian symbolism is found in John 3:14–15.

Cultural Symbolism

. I have asked research assistants and colleagues what they think when they hear “Jesus, the serpent.” They answer, “Jesus, the Devil.” Their response is immediate and no reflection seemed required. If we were able to ask members of the Johannine community what they might think if they heard that a man was thought of as a serpent, they most likely would answer that he was divine. At the outset, we need to be aware of the vast difference between two cultures: that of the United States in the twenty-first century and that of the Fourth Evangelist in the first century.

A study of serpent symbolism in antiquity has proved to be revealing. The first emperor of Rome, Augustus (63

BCE

-14

CE

), was considered a god, even if he suffered occasionally from diarrhea. The Roman historian Suetonius (c. 69-c. 140

CE

) in his only extant work,

The Twelve Caesars

, recorded the following startling account of the birth of Augustus Caesar:

71

Then there is a story which I found in a book called

Theologumena

, by Asclepiades of Mendes. Augustus’ mother, Atia, with certain married women friends, once attended a solemn midnight service at the Temple of Apollo, where she had her litter set down, and presently fell asleep as the others also did. Suddenly a

serpent

glided up, entered her, and then glided away again. On awakening, she purified herself, as if after intimacy with her husband. An irremovable coloured mark in the shape of a

serpent

, which then appeared on her body, made her ashamed to visit the public baths any more; and the

birth of Augustus

nine months later suggested a

divine paternity.

72

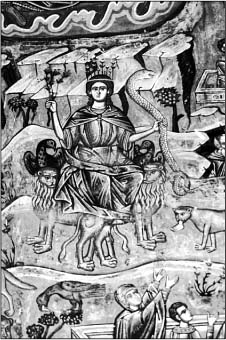

Figure 82

. The Resurrection. Christ holding a serpent. Mount Athos, Philopaedia Monastery. JHC

The spirit of the time when the Fourth Gospel was composed was imbued with the understanding and belief that serpents were positive symbols. The story of Augustus’ birth from a serpent (although it was also acknowledged that he was the son of a

novus homo)

was well known and widely assumed to be accurate.

73

It shaped beliefs, myths, and reflections on other individuals deemed divine. Augustus was none other than the son of Apollo, the son of Jupiter and Latona.

In evaluating this story of Augustus’ “divine paternity” by the great god, Apollo-Zeus, it is imperative to observe that Suetonius’ account of the lives of the Caesars continues until the death of Domitian in 96

CE

. That is about the time the Fourth Gospel reached its completion, or second edition.

74

During the time the Fourth Gospel was taking shape and moving through two editions,

75

the divinity of Augustus was widely expressed in terms of serpent imagery. It is thus prudent to ponder how and in what ways the Fourth Evangelist sought to stress Jesus’ divinity by interpreting Numbers 21 so that Jesus is presented like Moses’ upraised serpent.

The Fourth Evangelist completed his second edition of the Fourth Gospel about 95

CE

, at which time he added the Logos Hymn (Jn 1:1–18), which was most likely chanted in the Johannine “school,” and other sections of his Gospel, especially chapter 21. Also about 95

CE

, Philo of Byblos was working on his compositions. As we have already seen, he discusses the divine nature of serpents. Philo of Byblos emphasizes that the serpent sheds its skin and so is immortal. Philo of Byblos refers to his own monograph, called

Ethothion

. In it he claims to “demonstrate” that the serpent is “immortal and that it dissolves into itself … for this sort of animal does not die an ordinary death unless it is violently struck. The Phoenicians call it ‘Good Demon.’ Similarly the Egyptians give it a name, Kneph, and they also give it the head of a hawk, because of the hawk’s active character.”

76

We can read portions of the

Ethothion

, which is lost, because Eusebius, the first Christian historian, cites it. According to Eusebius’ citation, Philo of Byblos calls the serpent “exceedingly long-lived, and by nature not only does it slough off old age and become rejuvenated,

77

but it also attains greater growth. When it fulfills its determined limit, it is consumed into itself, as Taautos himself similarly narrates in his sacred writings. Therefore, this animal is included in the rites and mysteries.”

78