The Good and Evil Serpent (125 page)

Read The Good and Evil Serpent Online

Authors: James H. Charlesworth

5. | “serpent” | Gen 3:1 | P |

| | | Gen 49:17, Ps 140:4[3] | N |

| | | Exod 4:3, 7:15 | P |

| | | Prov 23:31, Ps 58:5[4] | N |

| | | Isa 14:29 | P for Israel |

| Fundamentally Mythological Terms for Snake or Serpent | | ||

4. | “Leviathan” | Isa 27:1 | N |

12. | “Rahab” | Ps 89:11, Isa 51:9–11 | N |

| | | Job 9:13–14, 26:12–13 | N |

| | | Job 3:8; 40:25[41:1] | N |

| | | Ps 74:14 | B? |

18. | “dragon” | Ps 91:13, Job 3:8 | N |

The Ancient Hebrews and Snake Physiology

The snake was well known in ancient Israel. It seems obvious, from a close examination of the Hebrew Bible, that Israelites had carefully studied the snake and knew its physical characteristics. The zoological information regarding the snake or serpent in the Hebrew Bible often reflects careful observations.

253

Thus, the snake:

- lives, or hides, in the desert (Deut 8:15), under a rock (Prov 30:19), or in the sea (Amos 9:3)

- builds a nest in which it hatches its young (Isa 34:15)

- moves in an unusual way (Num 21:7,9)

- strikes suddenly (Gen 49:17)

- has a deadly bite (Gen 3:15, Amos 5:19, Ps 58:5[4], Job 20:14)

- has a forked tongue (Ps 140:4[3]), hisses (Jer 46:22)

- devours other snakes (Exod 7:12)

- eats dust with its prey (Mic 7:17, Isa 65:25)

Except in the Golan and Negev, in which the large black snake is appreciated for its protection of crops from mice and other harmful rodents, most Israelis today fear snakes and seldom see one. Perhaps only an Israeli ophiologist could match the ophidian knowledge of Isaiah and his school.

Conclusion

The symbol of the serpent is multidimensional in biblical Hebrew. In the Hebrew Bible, serpents are used to represent both a negative and a positive symbol. The upraised serpent made by Moses is a symbol that helps save people from deadly bites (Num 21), and the other positive uses of serpent symbolism reflected in the Hebrew Bible lead me to disagree with Fabry, who contends: “Nowhere in ancient Israel do we find any possibility of developing a positive attitude toward serpents.”

254

There certainly was no serpent cult in biblical theology, but there probably were at least innuendoes of such cults in the religions of ancient Israel. Hezekiah had to banish from the Temple precincts those who were devotees of and probably worshipped (perhaps through) Nechushtan. Overall, it is surprising how Isaiah and the School of Isaiah stand out in the Hebrew Bible in terms of an interest in serpents, as represented by Hebrew philology.

Finally, any attempt to be precise in terminology—except in English words to represent Hebrew nouns—fails to realize that the ancients did not develop a taxonomy for animals. Even Aristotle’s

Historia Animalium

is a factual survey; he did not try to construct a system for classification.

255

As F. S. Bodenheimer stated in

Animal and Man in Bible Lands:

“[T]he large majority of animal names of the Old Testament are definitely

nomina nuda:

empty names which cannot be ascribed to any species, and often even not to a definite class of animals.”

256

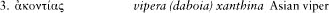

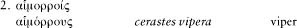

Appendix II: A Lexicon of Words for “Serpent” in Ancient Greek

Though Latin has primarily only two words to denote “snake” (

serpens

and

ser-pula

), and Coptic scribes usually chose only one word to translate many Greek words for “snake,”

1

the ancient Greeks developed, by the first century

CE

, an extraordinarily rich vocabulary for snakes. While there are eighteen nouns that denote a snake or serpent in the Hebrew Bible (see

Appendix I

),

2

forty-one words probably denote a type of snake in ancient Greek texts.

3

In

Die Schlangennamen in den ägyptischen und griechischen Giftbüchern

, C. Leitz reported on Greek names for serpents in an ancient book on poison.

4

This list significantly increases our knowledge of ancient Greek words for the various types of snakes; however, it needs to be supplemented by the names for the mythical or legendary serpents that are found in E. Küster’s

Die Schlange in der griechischen Kunst und Religion

(on p. 56), a noun in the Septuagint, one in the Greek Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, and studies of lexicons and ancient Greek texts. In order to be consistent, I have organized the Greek nouns in terms of the classical definition and English equivalent; as will be evident, some Greek terms represent the same English noun. I shall now present the Greek, Latin

termini technici

, and English words for snakes known to the ancients who knew or spoke Greek.

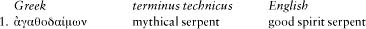

This “good spirit serpent” or “good Genius serpent” produces good (

agathopoieö

) because it is benevolent (

agathotheles

). It was especially popular in Alexandria, but also appears throughout the Greek and Roman world; for example, a fresco featuring Agathadaimon was found in Pompeii. The noun ‘ specifies devotees of the god Agathadaimon.

specifies devotees of the god Agathadaimon.

5

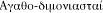

This “viper” is probably so named because of the “discharge of blood” (

haimor-roia

) when a person is bitten by it (cf. Epiphanius,

Pan

. 48.15).

6

This explanation is also supported by comments by the third-century

CE

physician named Philumenus (De

Venenatis Animalibus

21) and the second-century

BCE

Epicurean named Nicander (

Theriaca

282).

7