The Giza Power Plant (17 page)

There is much to be learned from our distant ancestors, if only we can open our minds and accept that another civilization from a distant epoch may have developed manufacturing techniques that are as great as or perhaps even greater than our own. As we assimilate new data and new views of old data, we are wise to heed the advice Petrie gave to an American who visited him during his research at Giza. The man expressed a feeling that he had been to a funeral after hearing Petrie's findings, which had evidently shattered some favorite pyramid theory he had at the time. Petrie said, "By all means let the old theories have a decent burial; though we should take care that in our haste none of the wounded ones are buried

alive."

3

With such a convincing collection of artifacts that prove the existence of precision machinery in ancient Egypt, the idea that the Great Pyramid was built by an advanced civilization that inhabited the Earth thousands of years ago becomes more admissible. I am not proposing that this civilization was more advanced technologically than ours on all levels, but it does appear that as far as masonry work and construction are concerned they were exceeding current capabilities and specifications. Making routine work

of precision machining huge pieces of extremely hard igneous rock is astonishingly impressive.

Considered logically, the pyramid builders must have developed their knowledge in the same manner any civilization wouldâreaching their state of the art through technological progress over many years. As of this writing, there is considerable research being conducted by professionals throughout the world who are determined to find answers to the many unsolved mysteries indicating that our planet has supported other advanced societies in the distant past. Perhaps when this new knowledge and insight are assimilated, the history books will be rewritten and, if humankind is able to learn from historical events, then perhaps the greatest lesson we can learn is now being formulated for the benefit of future generations. New technology and advances in the sciences are enabling us to take a closer look at the foundations upon which world history has been built, and these foundations seem to be crumbling. It would be illogical, therefore, to dogmatically adhere to any theoretical point concerning ancient civilizations.

Such a revisioning occurred in 1986 when a French chemist named Joseph Davidovits rocked the world with a startling new theory on pyramid construction. Davidovits proposed that the blocks used to construct the pyramids and temples in Egypt were actually cast in place by pouring geopolymer materials into molds. In 1982, Davidovits analyzed limestone, given to him by French Egyptologist Jean-Philippe Lauer, which was taken from the Ascending Passage of the Great Pyramid and also the outer casing stones of the pyramid of Teti. In his book

The Pyramids: An Enigma Solved,

coauthored with Margie Morris, he reported:

X-ray chemical analysis detects bulk chemical composition. These tests undoubtedly show that Lauer's samples are man-made. The samples contain mineral elements highly uncommon in natural limestone, and these foreign minerals can take part in the production of geopolymeric binder.

The sample from the Teti pyramid is lighter in density than the sample from Khufu's pyramid (the Great Pyramid). The Teti sample is weak and extremely weathered, and it lacks one of the minerals found in the sample from the Great Pyramid. The samples contain

some phosphate minerals, one of which was identified as brushite, which is thought to represent an organic material occurring in bird droppings, bone, and teeth, but it would be rare to find brushite in natural

limestone.

4

Davidovits' theory received worldwide attention, and I was challenged by several people to reconcile the theory that I was proposing with his. I have no difficulty reconciling my analysis of the cutting methods of the ancient pyramid builders with what Davidovits proposed. And I am sure he will see our individual efforts in the same light.

Davidovits cited

Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh,

in which Petrie devoted an entire chapter to the tool marks found on various artifacts made of both igneous and sedimentary rock. These artifacts were found both inside and outside the Great Pyramid. The tool marks on the stone tell us that they were cut, not poured. Nevertheless, this oversight should not entirely discredit Davidovits' findings. Construction technology today employs many techniquesâcutting, forming, and pouring to name a few. Thus I believe it is shortsighted for me, or for anyone else, to discover one method of manufacture or construction and present it as the only method used by the pyramid builders.

Davidovits made a strong argument for his cast-in-place theory by pointing out the impossibility of the Egyptians having moved the huge monolithic blocks of stone that were used to build the pyramids. In most construction projects, if there is an option to do so, it does make sense to prepare a mold, or form, and pour the material, if the alternative is lifting and moving large masses weighing up to two hundred tons. Davidovits claimed that he had solved the problems associated with moving such huge stones with his cast-in-place theory. However, evidence that argues against the casting of igneous-type rock can be found in the rock tunnels at Saqqara. These are the giant granite and basalt boxes that weigh in at around eighty tons each. The existence of a roughed-out box and more than twenty finished boxes situated underground essentially disproves the argument that they were cast. We can speculate that when the craftspeople finished working the rough box, which is now wedged in one of the underground passageways, they would have had to move it into place without the benefit of

hundreds of workers. That in and of itself is an impossibility. Furthermore, the very fact that this one box is rough cut belies the use of a casting method. If the Egyptians had cast these objects, they would not have chosen the characteristics of the roughed-out box for their mold. The product would be much closer to the finished dimensions of the other boxes, and more than likely the surfaces would be flatter than they actually are. These speculations do not mean that the ancient Egyptians did not use geopolymers. They simply mean that there may have been more than one method used to build the pyramids. To bring this whole issue into clearer perspective, perhaps we should now pause from evaluating the artifacts themselves and consider the work of an eccentric visionary who came before Davidovits, a man who also claimed he knew the secret of how the pyramids of Egypt were builtâand succeeded in proving it.

Chapter Six

THE CORAL CASTLE MYSTERY

W

hile the cutting techniques of the ancient pyramid builders have

been an ongoing topic for debate, they have not received the same attention and controversy as the methods that were used to lift and transport cyclopean blocks of stone. Egyptologists and orthodox believers of primitive methods argue that the huge blocks were moved and positioned using only manpower, but experts in moving heavy weights using modern cranes throw doubt on their theory.

My company recently installed a hydraulic press that weighs sixty-five tons. In order to lift it and lower it through the roof, they had to bring in a special crane. The crane was brought to the site in pieces transported from eighty miles away over a period of five days. After fifteen semitrailer loads, the crane was finally assembled and ready for use. As the press was lowered into its specially prepared pit, I asked one of the riggers about the heaviest weight he had lifted. He claimed that it was a 110-ton nuclear power plant vessel. When I related to him the seventy-and two hundred-ton weights of the blocks of stone used inside the Great Pyramid and the Valley Temple, he expressed amazement and disbelief at the primitive methods Egyptologists claim were used.

For many of us to whom the Egyptologists' orthodox theory seems implausible, it is enough just to argue the issue from a logical standpoint. For others, the debate becomes more meaningful when a proposed alternate method is demonstrated and proven to be successful. For that proof we must turn to the one man in the world who, by demonstration, has supported the claim, "I know the secret of how the pyramids of Egypt were built!" That man was Edward Leedskalnin, an eccentric Latvian who immigrated to the United States and who is now deceased. But he left many intriguing clues that persuade us he may indeed have known such secrets.

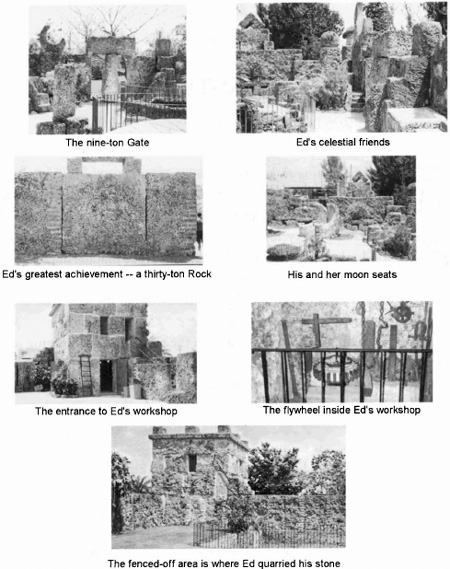

FIGURE 25.

Assorted Photographs of Coral Castle

Leedskalnin devised a means to single-handedly lift and maneuver blocks of coral weighing up to thirty tons. In Homestead, Florida, using his closely guarded secret, he was able to quarry and construct an entire complex of monolithic coral blocks in an arrangement that reflected his own unique character. On average, the weight of a single block used in the Coral

Castle was greater than those used to build the Great Pyramid. He labored for twenty-eight years to complete the work, which consisted of a total of 1,100 tons of rock. What was Leedskalnin's secret? Is it possible for a 5-foot tall, 110-pound man to accomplish such a feat without knowing techniques that are undiscovered to our mainstream contemporary understanding of physics and mechanics?

Leedskalnin was a student of the universe. Within his castle walls, he had a 22-ton obelisk, a 22-ton moon block, a 23-ton Jupiter block, a Saturn block, a 9-ton gate, a coral rocking chair that weighed 3 tons, and numerous other items. A huge 30-ton block, which he considered to be his major achievement, was crowned with a gable-shaped rock. Leedskalnin somehow single-handedly created and moved these massive objects without the benefit of cranes and other heavy machinery, a feat that astounds many engineers and technologists, who compare these achievements with those employed by workers handling similar weights in industry today.

Leedskalnin's castle was not always located in Homestead, Florida. He thought he had found his Shangri-la near Florida City and was happily working away on his rock garden until one night several thugs attacked him. Being a small man, he was an easy mark for these cowards, and he became a changed man after the trauma. Such was his concern that he became obsessed with moving his rock garden to a safer area. To assist him in the effort, he contracted with a local truck driver to haul his large rocks from Florida City to Homestead. As they prepared to load a 20-ton obelisk onto the truck, Leedskalnin asked the truck driver to leave him alone for a moment. Once out of sight, the truck driver heard a loud crash. Hurrying back to his truck, he was stopped in his tracks by the sight before him, hardly believing his eyes. He had returned just in time to

see

Leedskalnin dusting off his hands, the huge obelisk loaded and weighing down his flatbed.

Once in Homestead, the trucker was asked to leave his flatbed overnight and return in the morning. He was doubtful that Leedskalnin would be able to fulfill his promise that the obelisk would be off the truck and erected in the place he had set out for it. It's a good thing the truck driver did not bet money against Leedskalnin's ability to fulfill his word, because when he returned the following morning, Leedskalnin had moved the monolith into position, just as he had promised.

For his stupendous feats of construction engineering, Leedskalnin received attention not only from engineers and technologists, but from the United States Government, who paid him a visit, hoping to be enlightened. Leedskalnin received the officials gracefully, but they left none the wiser. In 1952, falling ill and on his last legs, Leedskalnin checked himself into the hospital and slipped away from this life, taking his secrets about moving massive objects with him.

If we assume that Leedskalnin and the ancient pyramid builders were using similar techniques, we must reevaluate the requirements for the man-hours necessary to construct the Great Pyramid. Estimates provided by Egyptologists for the number of workers that built the Great Pyramid range between 20,000 and 100,000. Based on the abilities of this one man, quarrying and erecting a total of 1,100 tons of rock over a time span of twenty-eight years, the 5,273,834 tons of stone built into the Great Pyramid could have been quarried and put in place by only 4,794 workers. If we figure in the efficiencies to be gained from working in teams and the division of labor, we can reduce the number of workers and/or shorten the time needed to complete the task. Let us not forget the estimate given by Merle Booker of the Indiana Limestone Institute for the delivery of enough limestone to build a Great Pyramid. Using the same criteriaâwith respect to size and quantityâas the ancient builders, but using modern equipment, Booker estimated that all thirty-three Indiana limestone quarries would have to triple their average output to produce the stone. His estimate did not factor in any equipment failures, labor disputes, or acts of God. He estimated that

twenty-seven years

after the order was placed, the last stone would have been delivered! These numbers put Leedskalnin's accomplishments in their proper perspective.

I first visited Coral Castle in 1982 while vacationing in Florida. It soon became clear to me that Leedskalnin's claim was accurateâhe did indeed know some secrets, perhaps even the very ones used by the ancient Egyptians. I returned to Homestead again in April 1995 to refresh my memory and, specifically, to closely examine a device that, in 1992, fueled a discussion between an engineer colleague, Steven Defenbaugh, and myself. Our discussion resulted in a speculation as to the methods that Leedskalnin had used.

Leedskalnin took issue with modern science's understanding of nature. He flatly stated that scientists are wrong. His concept of nature was simple: All matter consists of individual magnets, and it is the movement of these magnets within materials and through space that produces measurable phenomenaâthat is, magnetism and electricity and so on.

Whether Leedskalnin was right or wrong in his assertions, from his simple premise he was able to devise a means to single-handedly elevate and maneuver large weights, which would be impossible using conventional methods. There is speculation that he was employing electromagnetism to eliminate or reduce the gravitational pull of the Earth. These speculations are entertained by some and scoffed at by others whose feet are firmly planted in the "real world."

While at Coral Castle, I commented to a lady standing in Leedskalnin's workshop that it was quite a feat he had performed, and asked if she had any idea how he had done it. Fixing me with a measured look, she said, "Through the application of physics and mechanics such work can be done." Somehow sensing my esoteric bent, she commented that Thor Heyerdahl had dispatched wild speculation about how the huge stone statues on Easter Island were put in place when he reenacted the work by carving, moving, and erecting one.

Being alone, and wanting a photograph taken of myself in Leedskalnin's workshop, I did not want to be argumentative. Smiling, I handed her the camera and did not point out that Heyerdahl, unlike Leedskalnin, had an ample supply of willing and healthy natives. They provided sufficient manpower to satisfy the physical requirements for conventionally moving such large weights, even on rollers, and cantilevering them into an upright position. Heyerdahl was an energetic man, but, using those methods, he could not have done it alone. Moreover, Heyerdahl merely demonstrated that the job could be done using one particular method. Anyone who has worked in manufacturing knows that there are many ways of doing things. To devise a means to perform a given work and present it as the only way that such work could be done gives little credit to those who either might know of a better way or might look for a better methodâand succeed in finding one.

When analyzing ancient engineering feats, and being faced with explaining technically difficult tasks, Egyptologists and archaeologists typically

throw in more time and more people using primitive, simple tools and manpower. Unlike those conventional arguments regarding ancient civilizations, in the case of Ed Leedskalnin we cannot impose the view that the work was done employing masses of people, for it is well-documented that Leedskalnin worked alone.

Egyptologists claim to "know" how the Great Pyramid was built. To prove it, stones no heavier than two-and-one-half tons were hefted into place using a gang of workers, straining on ropes. Leedskalnin claimed to "know" how the Great Pyramid was built, and to prove it he moved a thirty-ton and other monolithic blocks of coral to build his castle. It is too bad the cameras were not on Leedskalnin as they were on the

NOVA

experiment. I believe that Leedskalnin's feat is more illustrative of the pyramid builders' methods. While I enjoyed

This Old Pyramid,

I was not too impressed with the results. After a tremendous amount of effort using modern tools and equipment, the crew managed to move a few blocks into place using only manpower. After recently talking to Roger Hopkins, who was the mason in charge of the construction of the pyramid for the

NOVA

film, I have a lot more respect for the effort and knowledge that he put into it under extremely arduous conditions. Hopkins is very straightforward and an honest craftsman who specializes in working in granite. Like me, he is convinced that the ancients were using state-of-the-art equipment to perform this work.

But the equipment and techniques Leedskalnin used, I would suggest, go beyond what we know as state of the art. What technique did he use? Can we regain the knowledge he took with him to his grave? What follows is a speculation about the techniques Leedskalnin may have used. It follows his basic premise regarding the nature of electricity and magnetism and leads to a conclusion that, I believe, has some semblance of logic. This speculation followed some basic rules for brainstormingâthose that follow and that might eventually reveal the secret should do the same. First, there is no such thing as a stupid idea, and, second, what we have been taught about the subject may not necessarily apply when seeking and, hopefully, finding a real solution.

A paradigm shift in my perception of "antigravity" occurred when my coworker, Steven Defenbaugh, and I were discussing the subject with Judd Peck, the CEO of the company for which we both work. Peck asked the

simple question, "What is antigravity?" In an attempt to define it I had to say, "A means by which objects can be lifted, overcoming the gravitational pull of the Earth." As I spoke, it occurred to me that we were already applying antigravitational techniques in our everyday life. When we get out of bed in the morning, we employ antigravity just by standing up. An airplane, a rocket, a forklift truck, and an elevator are technologies devised to overcome the effects of gravity. Even a car rolling along on its wheels is an antigravity device. Without the wheels and a propulsion system, it would be just dead weight.