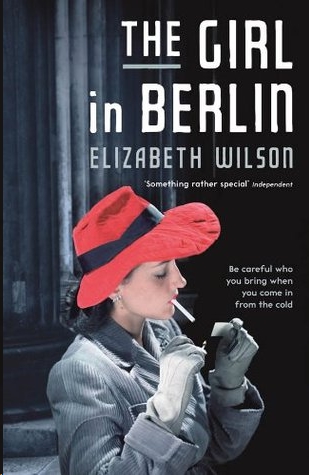

The Girl in Berlin

Read The Girl in Berlin Online

Authors: Elizabeth Wilson

ELIZABETH WILSON

is a researcher and writer best known for her books on feminism and popular culture. She is currently Visiting Professor at the London College of Fashion. Her novels

The Twilight Hour

and

War Damage

are also published by Serpent’s Tail.

Praise for

The Twilight Hour

‘This is an atmospheric book in which foggy, half-ruined London is as much a character as the artists and good-time girls who wander through its pages. It would be selfish to hope for more thrillers from Wilson, who has other intellectual fish to fry, but

The Twilight Hour

is so good that such selfishness is inevitable’

Time Out

‘A vivid portrait of bohemian life in Fitzrovia during the austerity of 1947 and the coldest winter of the twentieth century’

Literary Review

‘A book to read during the heatwave to keep you cool. The observant writing ensures that the iciness of the winter of 1947 rises off the page to nip your fingers … [An] exciting, quirky story and a gripping evocation of an icy time’

Independent

‘Fantastically atmospheric … The cinematic quality of the novel, written as if it were a black and white film with the sort of breathy dialogue that reminds you of

Brief Encounter

, is its trump card’

Sunday Express

‘An elegantly nostalgic, noir thriller; brilliantly conjures up the rackety confusion of Cold War London’

Daily Mail

Praise for

War Damage

‘[A] first class whodunit … The portrait of Austerity Britain is masterfully done … the most fascinating character in this impressive work is the exhausted capital itself’ Julia Handford,

Sunday Telegraph

‘[Wilson] evokes louche, bohemian NW3 with skill and relish’ John O’Connell,

Guardian

‘The era of austerity after the Second World War makes an entertaining and convincing backdrop to Elizabeth Wilson’s fine second novel … A delight to read’ Marcel Berlins,

The Times

‘This book is as stylish as one would hope. An evocative, escapist tale of murder and secrecy in post-war London,

War Damage

paints a picture of a city that, way before the ’60s (even in the rubble of the Blitz), was swinging’ Lauren Laverne,

Grazia

‘

War Damage

captures the murky, exhausted feel of post-war London. Buildings and lives are being reconstructed and shady pasts covered over. The atmosphere of secrecy and claustrophobia is as thick as the swirling dust of recently bombed buildings. Wilson excels at a good story set in exquisite period detail’ Jane Cholmeley

‘Cultural historian Elizabeth Wilson used post-second World War austerity Britain as the setting for a crime novel in her atmospheric

The Twilight Hour

(2006), set around bohemian Fitzrovia and Brighton in 1947. In this loose sequel, she again brilliantly evokes that bleak world of bomb sites and food shortages … Wilson presents a nation struggling to get back on its feet, but she does not overdo the period detail … Regine is an idiosyncratic, vivid protagonist’ Peter Guttridge,

Observer

‘[A] sleek and vivid period piece’

Gay Times

The Girl in Berlin

Elizabeth Wilson

A complete catalogue record for this book can be obtained from the British Library on request

The right of Elizabeth Wilson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

Copyright © 2012 Elizabeth Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published in 2012 by Serpent’s Tail,

an imprint of Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

London EC1R 0JH

website:

www.serpentstail.com

ISBN 978 1 84668 826 3

eISBN 978 1 84765 808 1

Designed and typeset by [email protected]

Printed by Clays, Bungay, Suffolk

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For John and Katherine Gieve with thanks for all your support

one

May 1951

J

ACK MCGOVERN’S GLANCE

swept the scene as he stepped off the Glasgow train. A beam of sunlight pierced the grimed glass roof. Steam billowed upwards from farting engines. Wrapped in the solitude of the crowd, he watched as his fellow passengers fanned out across the concourse and scattered, drawn towards the exit like lemmings.

The rush and echoing noise exhilarated him. The anticipation never failed, was always like the first time: he’d come to conquer London. Cast off the past. London was the future, his future, a place of light and brightness after the dark, rainsoaked north. London was freedom.

He’d had a seat on the journey south, but his long legs had been cramped and he’d had nothing to drink but one bottled beer. The carriage, crowded with dozing passengers, had been draughty and at the same time sweaty, and the best he’d managed was a feverish doze. Now exhaustion was replaced by anticipation as he stood on the platform and took his bearings, quietly, from habit, observing those who hurried, and those who loitered or looked round, uncertain, caught between the excitement and anxiety of travel. Especially those who loitered. They were usually the interesting ones.

The pale, wolfhound eyes that missed nothing seemed unexpected, set in his dark, saturnine face. He’d read somewhere that olive skin and black hair came from the ancient Picts, the men who’d lived in the glens before the red-haired, pink-faced Vikings arrived, but perhaps his height came from the Norsemen, as he was tall for a Scot, five foot ten. Any hurrying passerby who glanced at him would have thought him a fine figure of a man, but few noticed him, because he had the art, so necessary in his job, of fading into the background. His trilby shaded his face, his tweeds were unremarkable, his movements smooth and subtle. In London he could disappear in the slipstream of seven million lives pouring through the labyrinth of the great city.

Had his left elbow not been shattered at Alamein, he might have stayed in his native land, but he could no longer lift his arm to shoulder height and that had ruled out both the army and the shipyards where his father had worked. So the injury had been a blessing in disguise, providing the opportunity to get away from the city and family he loved, but who constrained and oppressed him with their demands, their customs, their assumptions.

Nobody in the police force knew – and it continued to surprise him that they hadn’t bothered to find out – that his father had been a communist. In the tenement kitchens of his school mates you often saw the Virgin Mary, the Sacred Heart or a reproduction of

The Light of the World

beaming down, but in his home it was Uncle Joe, Comrade Stalin who watched kindly over them.

McGovern senior had swelled with pride when his son got the scholarship to grammar school, but the education he so strongly believed in had gradually placed a wedge between him and his son. Jack McGovern hadn’t followed his father into the shipyards. Instead he’d found an office job, but he was bored, so he enrolled at night class to study law, and somehow got in

with a bohemian crowd from the Art School. Among them was Lily. She and her middle-class, arty friends from Pollockshields and Hillhead had fascinated him and to them a worker’s son from Red Clydeside was exotic, a romantic figure in these socialist times.

To old McGovern the new friends were tempting the son away from his working-class roots. Father and son had argued fiercely and things came to a head when McGovern told his parents he was marrying a coloured girl. For Lily was half Indian.

Like Jack McGovern, she didn’t quite fit in. That – and because he wanted a different life – was why McGovern had left Glasgow, left Scotland, come to London and, almost on a whim, or to defy his father, joined the police.

He soon became a detective and now was seconded to the Special Branch. To be part of the state apparatus that spied on the workers was the ultimate act of a class traitor. And just as the Branch knew nothing about his background, so his father still didn’t know the whole truth about the path he’d chosen: that he was dedicated to crushing subversion in every form, whether it was striking workers, trades unionists, or even militant tenants’ movements. It was a secret he had to keep. His dad would have disowned him and he didn’t want that, although in fact he’d disowned his father, or at least his class. Yet he still respected his father and didn’t even know himself just why he’d rejected Glasgow and its fierce, proud workingclass way of life.

McGovern stood for several minutes, no longer surveying the crowd, but suddenly longing for Glasgow after all, not because of his residual love for the blackened tenements, the dark streets and the stunted, shrunken men in their flat caps trudging through the sooty fog that passed for air, but because Lily was still there.

He squared his shoulders and made for the exit. He was keen to get down to the Yard.

Three members of the Vice Squad were seated in the canteen and as McGovern closed in on them they were talking about the impending Messina trial. Gangsters; they loved that.

‘The defence’ll be bribery.’

‘Get away with you.’

‘Tell that to the marines.’

Hilarious. Then they looked up, slightly disappointed to see him back, but made room and were friendly enough. ‘Here’s the Prof.’

McGovern had to join in the laughter, but held himself superior to them. Most of them were bent: taking bribes, running toms. The bribery joke was only funny because everyone knew the gangster Messina had certainly had Vice Squad coppers in his pay at one time or another. Their double standards reeked of English hypocrisy. His methods, by contrast, were justified by their ends: to protect the state.

‘How’s Uncle Joe?’ That was a joke too. They scorned the Special Branch as much as he held their lot in contempt. He was alien to them. He was a boffin, wasn’t he, with all the stuff he knew about Commies, Nazis, the IRA. Not that people cared about fascists and republicans these days; it was all about the Reds now.

‘Comrade Stalin is well, thanks for the enquiry.’ He went along with the joke, although he knew, and they knew, it had a sting in its tail. It wasn’t the Branch, but MI5 who dealt with communist subversion. MI5 were in the saddle these days and his colleagues liked to remind him.

Behind that also lurked the suspicion that perhaps it wasn’t a joke at all. There was something about being a copper; you got tainted with what you were supposed to be fighting. Just as the Vice Squad were up to their necks in pornography and prostitution, so all the extremist ideologies they were supposed

to suppress contaminated McGovern and the Special Branch. It was a contagious disease and they were at risk from the infection because they were too close to the enemy. Furthermore, the Branch was distrusted on account of the aura of conspiracy that surrounded its officers. Their work took on the methods of their enemies: entrapment, blackmail and covert surveillance. To their fellow policemen, accustomed to the more straightforward methods of physical violence and bribery, they seemed sinister. Information, knowledge, after all, rather than the fist and the boot, were their professional weapons.

Above all they were just too brainy. They thought too much, were too clever by half. Such men were dangerous. Also, as McGovern freely admitted to himself, you had to be a bit unhinged to do the job. Men were drawn into this neck of the woods by some kind of obsession. He himself was fascinated by the conspirators he encountered, fanatics in thrall to a single obsessive idea.

He soon tired of sparring with his fellow detectives and escaped up to his poky office on the third floor. It got little daylight, because it looked out on a light well at the centre of the building, but McGovern liked it because it was out of the way and seldom attracted visitors. His assistant was seated at a desk against the wall, laboriously hand writing what McGovern assumed at a glance was some kind of report.

‘I thought you weren’t back till tomorrow, sir.’

Manfred Jarrell showed no surprise, but then there was little that surprised him. His accent suggested a privileged family or at least a public-school education, but he was as cagey as McGovern about his background. His hair, worn too long, was a violent shade of carrot orange, the contrast with which made his white, almost greenish, spotty complexion look even more sickly. Yet no-one ribbed him about his morbid looks or poncey accent.

‘Another bleeding

hin

tellectual! He’s going in with you,’ was

how Superintendent Gorch had introduced the lad. McGovern still didn’t know quite what to make of Jarrell, but had an uneasy feeling that the younger man had

him

worked out.