The Ghost in My Brain (19 page)

Read The Ghost in My Brain Online

Authors: Clark Elliott

So now what?

It turned out that Heather was (and still is!) a most completely excellent devout Buddhist person, around whom good things always seem to happen to others. A while after our sending the letters Heather ran into a woman at a party who had been to see a local cognitive restructuring specialist named Donalee Markus for a brain injury, and who raved about Markus's effectiveness. The next morning we called Dr. Markus (hereafter “Donalee,” as everyone calls her, but intended with the greatest respect and fondness), reached her on her cell phone, and began, in that moment, the transformation that gave me back my

life.

THE GHOST

RETURNS

Even in our first, brief phone conversation I found Donalee Markus inspiring. She is one of those people just bursting at the seams with life, and compassion, and goodwill. We traded information and agreed to meet at her home office.

Donalee is a

cognitive restructuring specialist

who practices clinically applied neuroscienceâmeaning that she reconfigures people's brains so that they see the world, and think, differently. To achieve her ends she has developed specialized visual puzzles that change the low-level building blocks of thought itself. She has treated hundreds of people over a thirty-year careerâmany of whom, like me, have suffered traumatic brain injuries. She has led seminars on maximizing intelligence for prestigious institutions like NASA and Los Alamos National Laboratory,

written books, appeared on television many times, and developed online intelligence-boosting puzzles.

Although Donalee is now past the age when many have already retired, she still rises by five every morning to get to work, and appears to have the energy of a woman in her twenties. The word “dynamo” comes to mind when you meet her in person. One can't help but be charmed.

On January 31st, 2008âmore than eight years after the crashâI met with Donalee at the beautiful Highland Park home she shares with her surgeon husband. We went downstairs into her basement office, and I sat across a table from her as we talked. We were surrounded by cheerful colors and interesting objects, including attractive candy binsâan indication of her work with childrenâand also a large number of file cabinets and drawers filled with many thousands of different cognitive puzzles. Donalee and I discussed a partial list of my symptoms, and also a list of my cognitive/personality weaknesses and strengths prior to the crash, both of which she had asked me to prepare in advance. I explained the difficulties I was having, and that I had more or less reached the end of the line, despite my best efforts to the contrary. To my surprise, she understood immediately about the unworkable cognitive load from my inability to filter out Erin's constant chatter.

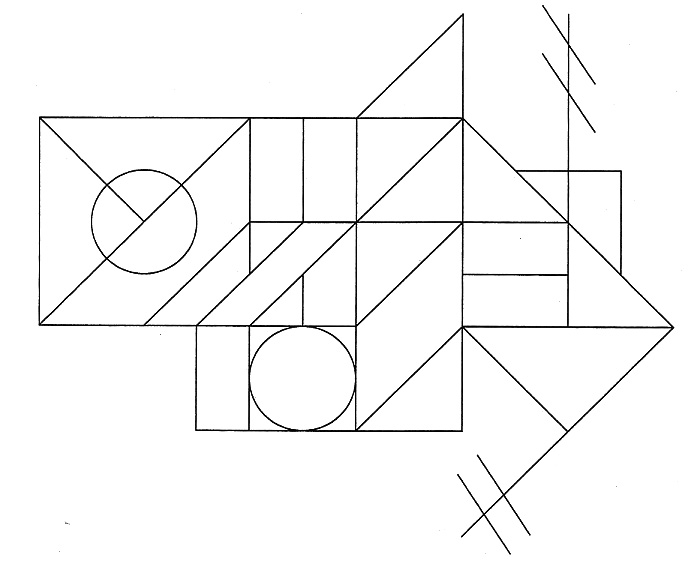

After some preliminaries during which I made drawings with colored markers, Donalee had me sit at a table and make a copy of the line-drawn design shown in

Figure 3

.

Looking at the drawing, I told Donalee that I knew exactly what was going to happen, and that within a few minutes I would be rather affected by the effort of what she was asking of meâeven though ordinarily it would be trivial to make a copy of so simple a figure. She wanted to see how I approached the task anyway, as this was one of her diagnostic tools. So I set about copying the abstract drawing onto a blank piece of paper.

Figure 3:

Complex Geometric Line Drawing

Within a minute I began to lose normal control of my muscles; my hands and upper body grew contorted. Over the course of the next five minutes, my symptoms steadily worsened. My eyes grew wide like saucers. I hunched over the paper with my head twisted sideways, about six inches from the table. I looked very much like a person having a neurological meltdownâlike an outwardly normal Professor Jekyll transforming before everyone's eyes into a bizarre Mr. Hyde with cerebral palsy. I stared intensely at minute pieces of the design, trying to make sense of them, to “see” them, so that I could make the transfer to the new page. I worked ever more slowly . . . slowly . . . slowly . . . methodically copying the simple lines and circles, and finally moving at the speed of a frame-by-frame slow-motion movie. My movements became increasingly uncoordinated as the muscles in my arms, neck, face, back, and hips knotted up. The paper got bunched and wrinkled as my left hand, holding it, became increasingly contorted. While completing the task I kept up a calm, joking dialogue in slightly

slurred speech, saying things like, “Well, as I said, this always happens. I try to avoid this kind of activity if I can help it.”

Donalee told me later that in watching me work she was stunned. She had never seen anything like it. Her assistant, Mara, who was in the room, was on the verge of calling 911âgiving hand signals to Donalee behind my back asking what to do. Only my calm, oddly juxtaposed, ongoing narrative convinced them to wait and see.

Despite the persistence of my symptoms, Donalee next gave me some simpler tests, and we talked. She had me try on various colored sunglasses: purple, magenta, aqua, and so on.

*

Surprisingly, the aqua and purple glasses seemed to help my neurological symptomsâmy coordination and balance improved, recovering slightly from the breakdown caused by the stress of her testsâand she gave me a pair of each to take home.

In those first two hours we spent working together, I found Donalee to be really engagingâsmart, organized, and compassionate. Her knowledge of clinically applied neurology was vast. I could tell that she “got it” right from the start. And critically important to understanding how she works is that she

pays close attention

to the people with whom she works. She is watching, and thinking, and asking, and listeningâteasing out small clues to what is going on in the brain.

Donalee told me she would think about what she had observed. I thanked her, and headed out.

As I left, Donalee was again taken aback at the difficulty I had making it through the doorway of her office. She didn't

know quite what to make of the weird gyrations I used to get my body up the stairs to the first floor: holding on to the wall, twisting my head around and tipping it sideways in odd ways, staring intently at tiny pieces of the visual landscape, raising my arms up as though to fend off an attack from the ceiling and walls as I tried to “see” them in some elemental, proprioceptive way. She was amazed at the deterioration that had taken place just from the simple diagnostic exercises she had given me. I assured her that it was nothing to worry aboutâthat this was normal and I had everything under control.

After I left, I felt quite unsettled. I had been to many doctors and the result was always the same: they never called back. When I went to see them, they had little to offer. I knew this, but once again had allowed myself just a little hope. And yet I saw that, after all, I was once again just going to have to face the fact that my life as I had known itânow almost a decade agoâwas well and truly over.

It was embarrassing to be at Donalee's and let on about the extent of my cognitive impairments, and it was saddening to be reminded of how even the simplest cognitive tasks were almost impossible for me to manage. Despite Donalee's obvious compassion, I felt like the humiliation of my life had just been rubbed in my face once again. It evoked unpleasant memories of the time I had gone to see the movie

Memento.

A new low, after all.

Erin, now three, was on a rare visit to the babysitter. So, instead of going home, I took a detour and went to the movies again. I spent several hours there just watching the scenes go by, drifting from theater to theater, not really able to understand what the movies were about, but letting the music, the dialogue, and the visual scenes wash over me in a multisensory montage.

In the late afternoon I went home. Just as I got up to my bedroom to rest for a few minutes before going to get Erin, the phone rang. It was Donalee.

She had called me back.

I couldn't believe it.

Donalee: “Where have you been? I've been trying to reach you all afternoon.”

Clark: “I'm sorry. I was upset about having you see me like that. So I went to the movies.”

Donalee: “Clark, I have some ideas about how we can approach this. I have a plan. We can deal with this. I don't like to sit around. I want to get this done.”

Clark: “What!?” (I was at a loss for wordsâI couldn't make sense of it.) “I don't know what to say . . . I don't understand.”

Donalee: “Why not? What are you talking about?”

Clark: “I've been to see lots of medical people over the last eight years. Once they get a look at me, no one has

ever

called me back.”

Donalee (brushing off my amazement): “Well, I'm different, and I know how to work on this problem. One thing I was trying to figure out was, how can you possibly work at all? I've seen how you are. I know exactly what's going on in your brain. There's no way you can work with that kind of brain damageâespecially as a professor.”

Clark: “To be honest, it hasn't been very easy.”

Donalee: “Then I realized what it is.

You're the guy that never gives upâever!

Right?”

Clark (pausing, thinking): “Hmm. Well, yes. That's who I am.”

Donalee (humorously): “Ever! . . . Ever!! . . . EVER!!!”

We both laughed.

Donalee: “I can work with that. We can fix this, Clark. I know where to start, and we'll take it from there. When can you come back to see me?”

And Dr. Donalee Markus was right. She

did

know what to do. This was the beginning of the brain-plasticity miracle that gave me back my life, and that we'll now see unfold

before my eyes.

Part of Donalee's plan was that I also work with a colleague of hers, Deborah Zelinsky, an optometrist who emphasizes neuro-optometric rehabilitation. Donalee's comment was “We can manage everything here at my office, but in your case it will probably go faster if you also work with Debbie. Go visit her and see what she says.”

So the following week I went to see Deborah Zelinsky, O.D., F.N.O.R.A., F.C.O.V.D.,

*

for the first time. Dr. Zelinsky (hereafter just “Zelinsky” as she seems often to be referred to, out of respect for her uniqueness, like “Bach” or “Einstein”) is a brilliantly innovative neuroscientist in a clinician's white coat. She

accesses the brain primarily through manipulating the light that passes through our retinas. Coming from an academic family that includes a former Northwestern University professor of mathematics, and a Caldecott Medal winner, Zelinsky regularly engages in scholarly activities such as giving seminars on her techniques in many European countries, attending scientific sessions, and occasionally chairing them. She was the 2013 recipient of the Neuro-Optometric Rehabilitation Association Founding Fathers Awardâa distinction she shares with the eminent scholar V. S. Ramachandran, who received the award in 1997. She has worked with the blind, the autistic, the developmentally delayed, those who have had traumatic brain injuries, children with learning problems, and other special populations. She serves as an expert witness for brain-injury cases.

Zelinsky maintains a suburban practice north of Chicago called

The Mind-Eye Connection

and between lectures that take her around the world sees patients as an optometrist who makes use of many neurodevelopmental rehabilitation techniques. Although she is a talented and practicing optometrist, and regularly prescribes glasses for patients, it is clear after spending just a few minutes with her that she is primarily focused on how the visual systems interact with brain function, and how the visual/spatial functions in the brain are integrated with the higher-order brain processing that makes us human.

When I first entered the Mind-Eye Connection offices, the immediate thought that came to mind was

friendly commotion.

Zelinsky's office, and lab, is the informal hub of not only a local, but also a national and even an international network of people wandering through one of the great, casual unfoldings in clinical brain science. On this visit there was a local high-school student sitting in the waiting area, there for a pair of glasses; a developmentally

challenged third grader from Ohio trying on frames in the display foyer; and a European neuroscience professor wandering out from one of the examination rooms where he had been chatting with a pair of top-notch optometry interns from California.

On the front desk there was a pair of glasses that needed a screw replaced, sitting next to some notes for a presentation on her work that Zelinsky was giving the following week. The receptionist was talking on the phone to a parent from Texas who was desperately trying to slip her child into Zelinsky's packed schedule. In the receptionist's free hand was Zelinsky's travel packet for yet another series of lectures she'd be giving in Europe later in the year.

Zelinsky herself came out of a different examination room holding a patient's folder, momentarily resumed the ongoing academic conversation she'd been having with the neuroscientist, then stopped to give a charming smile to the third graderâcomplimenting the little girl on her choice of frames. Zelinsky introduced herself to me, then handed me off to her assistant Martha.

In all I spent three hours that day in testing and diagnostic interviews, interleaved with the other patientsâfirst with Martha, and then with Zelinsky herself.

*

The later parts of the testing were conducted in Zelinsky's examination room, using her phoropter (the lens-swapping optometric machine that fits over a patient's face). Zelinsky took copious notes throughout the process, and often referred back to earlier test results as she tried different combinations of lenses.

Zelinsky explained that she would prescribe for me a special pair of glasses that included, among other things, prisms. They would not correct my eyesight the same way my regular glasses would, and they would not be useful for reading. She cautioned me about driving with them on. Beyond that, she wanted me to wear them as much as I could tolerateâit would take work on my part because the glasses were going to push my brain in the direction she wanted to take it. “Change is not always easy,” she said.

I had brought with me extensive notes on my symptoms, which I was prepared to discuss with Zelinsky. At Donalee's urging, I particularly wanted to go over with her the “visual brain seizures” that caused my body to contort and my limbs to shake from side to side under certain kinds of brain stress. Zelinsky was not the least bit impatient with me, but was understandably anxious to move on to the other appointments she had queued up. “I read through everything you brought me while you were working with Martha,” she explained. “We don't need to discuss your notes. I already know what's wrong with you.” I was a little taken aback. “And I know how to fix it,” she added, before giving me a quick nod and a smile, and then walking away to greet her next patient.

And indeed, she did know how to fix it.

A few days later I got my first pair of “brain glasses”âmy

Phase I

glasses, as I later came to call them. In the days that followed, my cognitive functioning improved dramaticallyâno, let's say astoundinglyâand for the first time in eight years I started to feel like a real human. The effect of the new glasses, along with the work I had started pursuing with Donalee, was stunning. Importantly, although it was tiring and challenging for me to make the transition, it also felt

right

.

Within the context of Donalee's simultaneous treatment, Zelinsky was able to achieve, for the price of an office visit and a pair of glassesâand within the course of ten short daysâwhat some of the leading neurologists in Chicago, and a famous rehabilitation center, and many others, had claimed would never happen: I started to get better.

While I was understandably blown away by the dramatic results, Zelinsky was mostly cavalier about it. She was, of course, happy that I was getting better, but she already knew what would happen because she had seen it many times before. She knew what she was doing. This was old hat for her.

I've preserved a letter I sent to Zelinsky just two weeks after getting my first pair of glasses, and in looking at excerpts from it we have a window onto this remarkable period during which my brain was starting to reconfigure itself.

Clark Elliott

[ . . . ]

Evanston, IL

28 February 2008

“THE MUSIC BEHIND MY EYES”

Dear Dr. Zelinsky,

Below are some further notes that fall into the “very strange” category. [ . . . ] I thought it best not to mention these current symptoms when I saw you in person because, well, they are just odd, and there wasn't time to explain.

However, since you were trying various glasses on me

with my eyes closed

on Tuesday (!), and since we did

briefly discuss the “blindsight” phenomenon involving non-visual retinal processing, it seems that I might best give you this additional data. I suppose I am trusting that you will not think me to be a mental case.

There are two (additional) not-at-all subtle alterations that coincide with my having worn the glasses for about ten days. However, they both have to do with my

hearing

.

First, some background: Before becoming a professor of Artificial Intelligence I attended the Eastman School of Music, and also spent time studying conducting, and trumpet, as a part-time student at the Juilliard School. I was one of the least naturally-talented

musicians

at either school. However, I was known as having one of the truly exceptional ears for “sound,” such that many recitalists would bring me in before concerts to tweak the hall, sound stage, and so on.

I left music school to have more time to devote to my musical ear. To this end, I spent more than a year listening to single notes, then gradually two, and then three, on the piano, roughly eight hours a day, studying their individual sounds, and developing my ear. I have continued to study music, and in particular musical

sound

, listening pretty much every day for the last thirty years, with a few years' forced hiatus after my brain injury.

Now fast forward to last week.

Strange Point One:

I typically listen to music with my eyes closed, and last week I began to notice something odd happening. With my glasses off (note: with my eyes CLOSED) I would hear the sound coming from my stereo speakers

(which were fourteen feet away) contained within the borders of an imaginary approximately 50 degree angle starting just behind my eyes and reaching toward infinity past the speakers. This was “normal.”

But, with the new glasses on (and my eyes closed), the sound stage instantaneously came about “ten feet” closer,

*

and, most dramatically, the angle of my “hearing-scape” changed to 180 degrees, extending in a straight line through just behind my eyes, and encompassing everything in front of that line.

For someone with ears as acute as mine, this is not a subtle difference.

What do I mean by my hearing being

different

? Well, this is a little hard to describe. I suppose I have always known that I “see” sounds. That is, I hear them, but I represent them as visual symbols. Sort of like: when listening intently I am not using my eyes at all, but I am hearing the sounds visually through my ears.

With the glasses on I have more than tripled the space in which I process the meaning of sound. But, it is much more profound than a face-value “3x” increase. For example, when I study music I use every available piece of

working memory

to store what I'll call “partial products of my listening process.” When this temporary, ephemeral space in which I can “see” and “hold” my hearing increases three-fold, I get an orders-of-magnitude increase in the complexity of sound that I can process.

Overall, the result is that there is an important and

dramatic qualitative increase in the depth of my listening, rather than a quantitative one.

The 180 degrees of my hearing (a 130 degree increase) applies primarily horizontally, but also, to a lesser degree, vertically.

Strange Point Two:

One point of immediate understanding with other people I have met who also have had serious TBI is that we understand one another when we say, “I am no longer human.” That is, in my case, I am sort of like a human, and I can fake it such that no one else notices, but something very tangible is missing. I imagine it to be like having had some kind of mystery lobotomy.

Starting around the middle of last week I started noticing an improvement with this problem. An old friend, like the ghost of who I used to beâthe real meâstarted following me around.

Although I cannot describe why this is so, “that” me seems strongly connected to my “180 degree hearing.” That is, he had to go somewhere else because he could not live in the impoverished representational sound-scape that I was able to support. But now, at least temporarily, and from time to time, I've had enough hearing space to get a glimpse of the old me.

We are listening, profoundly, through our magic internal eyes, to the rich world around us.

Best regards,

Clark