The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 (13 page)

Read The Gallant Pioneers: Rangers 1872 Online

Authors: Gary Ralston

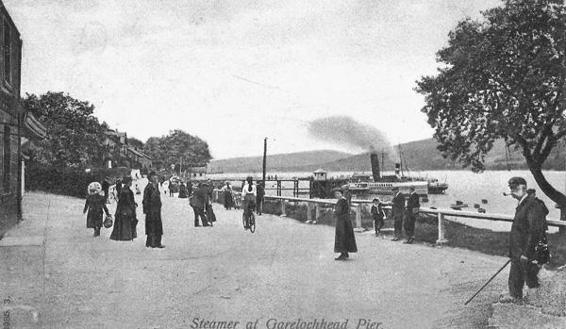

The pier at Garelochhead, a landmark that would have been more than familiar to Peter Campbell and his father, John.

The Campbells clearly had an entrepreneurial bent that allowed them to trade successfully in ships and develop new markets. Amazingly, this included an important role in the American Civil War for one of their vessels, the Mail, built in 1860 but sold three years later for the princely sum of £7,000 after its speed attracted the attention of Confederate agents looking for blockade runners in the Bahamas port of Nassau. The US Navy had been ordered to halt all maritime traffic in and out of Confederate ports, which caused the armies of the south considerable hardship. As an economy based mostly on agriculture, the southern states relied heavily on Europe for their essential military and medical supplies. As a result, Nassau and ports in Havana and Bermuda were used as staging posts, where supplies were loaded on to blockade runners such as the Mail and taken to the Gulf of Mexico, where they were distributed to those areas most in need. The Mail had been guided across the Atlantic in June 1863 by the Confederate conspirators and although she was captured by Union forces in 1864, dismissed as a prize and sold, she was actually bought by undercover agents again and once more returned to work as a blockade runner.

The last purchase involving John McLeod Campbell and Alexander Campbell was the Ardencaple in 1869, which ran on the Glasgow to Dumbarton route, with afternoon excursions to Greenock and Garelochhead. However, by the latter half of the 1860s the Campbell brothers had begun to progressively withdraw from the business they had founded, allowing their nephew Robert Campbell, ‘Captain Bob’ of Kilmun, to take it forward. In the case of John McLeod Campbell, poor health undoubtedly contributed to his decision to step back and allow Captain Bob to assume fuller control.

Peter’s father died on 13 May 1871 in Glasgow after a brief illness, aged only 56 years. His obituary in the Dumbarton Herald the week after his death described him as ‘one of the best known and most popular steamboat captains.’ It went on: ‘Few of any of the Firth stations were better liked by passengers and brother professionals than John Campbell. Shrewd, well-informed, careful, courteous and honourable, he merited the estimation in which he was held.’3 John left almost £1,300 in his will and the family continued to live at Craigellan for many decades, including his wife Mary, who died there on 12 May 1912, aged 89.

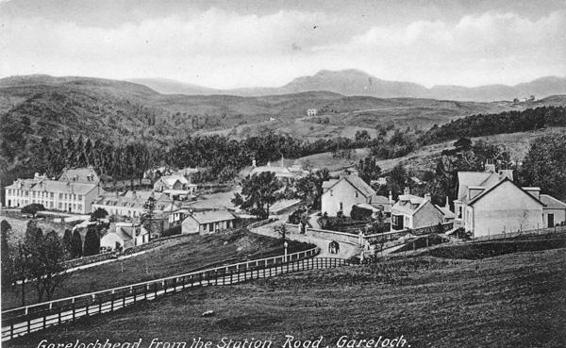

Garelochhead…a village the McNeil, Campbell and Vallance brothers knew intimately.

Even after the death of his father, Peter Campbell was clearly close to his cousin Captain Bob and his application for his certificate of marine competence in 1882 listed his address as No. 2 Parkgrove Terrace in Glasgow, the city residence of the steamship entrepreneur, who died in 1888. A year earlier, Captian Bob’s sons Peter and Alec had relocated the company to the Bristol Channel, their eyes having been opened by the financial possibilities of a business in a corner of England that had a sizeable population, but few passenger services of note. The company P. and A. Campbell dominated for decades, seeing off all competitors and in some cases buying out their fleets. It survived until the early 1980s when increased fuel and maintenance costs and an inevitable drop off in demand as the vogue for foreign holidays put paid to its existence.

The success and longevity of P. and A. Campbell, borne from the entrepreneurial zeal of John McLeod Campbell and his brother Alexander, made the death of Peter at the age of 25 all the more tragic, as fate denied him the opportunities afforded his relatives. The history of the Campbells of Kilmun makes no reference to Peter of Rangers fame – naturally, perhaps, as he played no role in their Clyde operations, but the impact he had on Scottish sporting culture has lasted longer than the considerable maritime achievements of his other family members. Peter was present at the birth of Rangers, but brothers John and James also gave the club sterling service in its early years and the family links with the McNeils remained strong in the second half of the 19th century. The 1881 census, for example, listed James as living with Moses, Peter and William McNeil and their sister Elizabeth at No. 169 Berkeley Street in Charing Cross, Glasgow.

Peter had arrived in Glasgow a decade earlier and was the youngest founder of Rangers, having just turned 15 when he embraced the idea of organising a team with his three friends, not least as a release from the toils of the work on the Glasgow shipyards where he was employed. His employment records, accessed from the historical vaults at Greenwich, show he spent five years as an apprentice with the oldest shipbuilding company on the Clyde in Glasgow, Barclay Curle, at Stobcross Engine Works between 1872 and 1877. John Barclay had started shipbuilding on the Clyde in 1818 and his yard lay half a mile outside the city boundary, on a patch of land near to the present-day Finnieston Crane, surrounded on three sides by open countryside. Facing the Stobcross Shipyard, on the south bank of the river, was the estate of Plantation, with the huts of the river’s salmon fishermen standing back from the river bank. It is almost impossible to imagine the site in the present day, where the Squinty Bridge now connects north and south of the river, alongside the Mecca bingo hall and Odeon cinema that make up one of the city’s best-known leisure parks.

In today’s post-industrial era the shipyards of the Clyde often struggle to compete, financially at least, with other areas of the world but in the 1860s, shortly before Peter began his apprenticeship with Barclay Curle, 80 per cent of British shipping tonnage was constructed on the Clyde. He would have worked in an industry at its peak in the 1870s as bigger and faster ships were built up and down the river. They included the exotic, such as the Livadia, built in 1880 at Fairfield for the Czar of Russia, and government contracts, not only in Britain, but estimated at half the maritime nations of the world – including Japan, who took control of the Asahi from the Clyde in 1899. Throughout most of the 19th century the shipyards of Glasgow proudly held the record for the speediest transatlantic crossings, with the firm grip of a rivet in an iron hull as Clyde-built ships were successful from 1840 to 1851, 1863 to 1872, 1880 to 1891 and 1892 to 1899. By the end of the century, Fairfield-built vessels Campania and Lucania could make the journey in five days and eight hours. In the 20th century great liners would maintain the reputation of Clyde shipbuilding, including the Lusitania, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth.

Peter stayed an additional two years with Barclay Curle as a journeyman from 1877–79 before leaving for at least seven spells at sea on board the London-registered merchant ship Margaret Banks, ranging in time from a fortnight to over six months. His apprenticeship served on the Clyde in Glasgow, he was clearly keen to extend his education to the waters of the wider world. As part of the process he sat engineering exams in March 1882, at Greenock and Glasgow, but failed each time on a poor grasp of arithmetic before passing at the third attempt the following month, on 12 April. Even the most mathematically gifted would surely have offered long odds on his death within 12 months, but betting on an extended life at sea has always been a dangerous gamble.

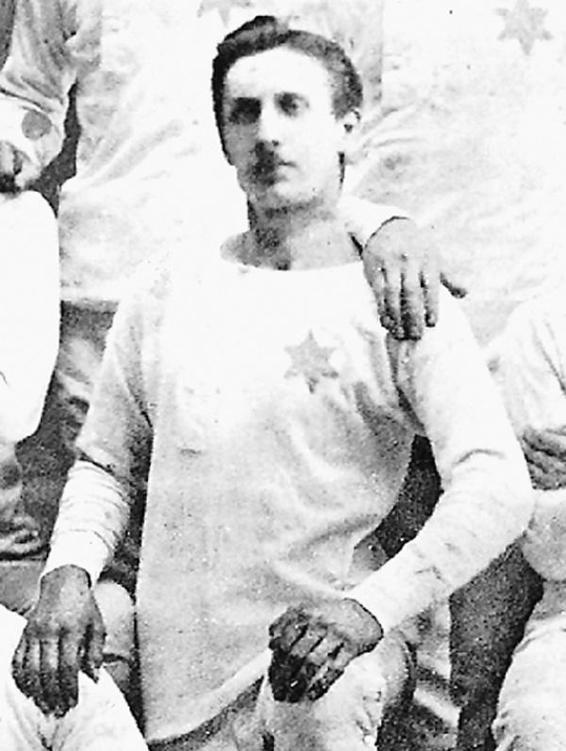

Campbell’s passion for the water was matched by his enthusiasm for football and he was an inspired supporter of Rangers, not to mention one of its most outstanding players throughout the 1870s, playing for the team in its very first match against Callander in May 1872 until he bowed out in a 5–1 Scottish Cup defeat to Queen’s Park in September 1879. He also spent part of a season at Blackburn Rovers from 1879 and was one of the first Rangers players to cross the border, at a time when the English game was being criticised for its ‘shameful’ move towards professionalism. Campbell and Moses McNeil had become the first Rangers players to win representative honours when they turned out for a Glasgow select against Sheffield at Bramall Lane in February 1876, helping their adopted city to a 2–0 victory. Campbell was twice chosen to represent Scotland, scoring a double in a 9–0 demolition of the Welsh at the first Hampden Park in March 1878 and following it up in April the following year with a single strike in a 3–0 victory against the same opposition at the Racecourse in Wrexham. He was also named vice-captain of the club in its earliest years and was renowned as a forward player of some repute, earning praise from Victorian sports historian D.D. Bone as ‘the life and soul of the forward division.’4 In the Scottish Football Annual of 1876–77 Campbell was described as a ‘very fast forward on the left, plays judiciously to his centre-forwards and is very dangerous among loose backs.’ Three years later, the same review book gushed: ‘Peter Campbell: one of Scotland’s choice forwards; has good speed, splendid dribbler and dodger and is most unselfish in his passing.’ Sadly, the last mention of Campbell in the Scottish Football Annual of 1881–82 featured him in a list of ‘Old Association Players Now Retired’. It read simply: ‘Peter Campbell: one of Scotland’s choice forwards; has good speed, splendid dribbler and dodger and is most unselfish in passing; gone to sea.’

Peter Campbell. This picture of the Rangers and Scotland winger from the 1877 Scottish Cup Final team is the only one currently known to exist.

Campbell’s love for football and Rangers was passed to siblings John and James, who played for the club in its earliest years before they sought a new life in other parts of the world. In February 1884, James left Glasgow for Australia to take up a post with the Union Bank of Melbourne. He lived to a ripe old age, dying in Brisbane in 1950. His younger brother Allan had also joined him in Australia and died in the same city in 1932, aged 72. John Campbell also emigrated, this time to the United States, and died in Middletown, New York, in 1902, aged approximately 46. Jessie Campbell lived until her late 70s before her death in 1931. The Campbell connection with Craigellan remained strong until 1939 when youngest daughter Mary, then aged 78, passed away at the family home.

Peter set off on Sunday 28 January 1883 from Penarth in South Wales on his second voyage with the St Columba, a 321-foot-long steamer of over 2,200 tons, which had been built on Merseyside in November 1880 for Liverpool company Rankin, Gilmour and Co., although the roots of the firm were Glaswegian. The St Columba was bound for Bombay with a cargo of coal, but it never got beyond the dangerous waters off the west coast of France and, with hindsight, it should never have left its berth near Cardiff Bay in the first place. The weather that weekend was dreadful and merited mention in the press at the time, as several disabled vessels ran into Plymouth harbour for shelter. The St Columba clearly entered a maelstrom and God only knows the horrors suffered by the crew in those final moments as the waves lashed the vessel, cruelly whipping them into the sea and certain death. The report sent from Cardiff five weeks later confirmed the terrifying circumstances and stated: ‘The missing steamer…was under the control of Captain Dumaresq and there is no doubt she was overpowered by the terrible weather which prevailed in the Bay of Biscay at the commencement of February.’5

The passing of Campbell did not go unnoticed in the Scottish game and ‘Scotsman’, writing in national publication Football: A Weekly Record of the Game, paid a particularly warm tribute. He wrote: ‘To most of us it is allotted that our virtues are not discovered till we cross the narrow isthmus that separates us from the great majority, but in the case of Mr Campbell, although our appreciation of his never failing amiability, his unchanging kindness, his tact as a club official and his brilliant play on the field may be intensified owing to the dire calamity, still, when in our midst he was so universally beloved that even his opponents on the field could not for a moment harbour any angry thought about him. It was he who, along with Thomas Vallance and Moses McNeil, nursed the Rangers in its days of infancy and brought it to the position which it held so honourably, and since business engagements forced these players to retire, the once famous and popular “Light Blues” have had rather an uneven career. Mr Campbell played for Scotland against Wales and for Glasgow against Sheffield, but he retired before representing his country against England. Memory is said to be short but it will be long – aye, very long, ere one of the truest and best of fellows shall be forgotten by his many friends.’6

The warm tribute of ‘Scotsman’ contrasted sharply with company owner Rankin’s words in a vanity publishing tome from the turn of the 20th century, A History of Our Firm, which, no doubt unwittingly, managed to read as disregarding and uncaring. His somewhat indifferent tone shone through as he discussed the company’s penchants for naming its vessels after saints in the 1880s. He rattled through the alphabet, from St Alban to St Winifred, before adding: ‘On our adverse experience of the letter “C” we have not repeated St Columba and St Cuthbert, whose losses were both accompanied by some loss of life. My brother always favoured Saints’ names taken from his favourite Sir Walter Scott.’8

In a later chapter, however, he reflects on the company’s low points. He wrote: ‘I draw a veil over the ghastly period wherein the ships St Mirren, St Maur and St Malcolm disappeared with all on board. It was a terrible time. At a later date the St Columba under Captain Dumaresq was never heard of. I may have been overwrought, but a vivid dream wherein I saw her sinking is often times with me still. I pray that we may never have again to pass through such a time. Captain Davey, who has revised these notes, told me Mrs Dumaresq had a similar dream, of which she informed Mrs Davey at the time. If I have written mostly of disasters it is to be said they have been relatively few. Successful voyages have largely predominated, but these are usually uneventful.’

If only Peter Campbell had lived long enough to be able to recollect the same.