The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 (77 page)

Read The Fall of Paris: The Siege and the Commune 1870-71 Online

Authors: Alistair Horne

Tags: #History, #Europe, #General

But it was through the medium of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, one year old at the time of the Commune and later known as Lenin, that the Commune and Marx’s interpretation of it was to have the most cosmic effect. All through his life Lenin studied the Commune; worshipped its herosim, analysed its successes, criticized its faults, and compared its failures with the failure of the abortive Russian revolution of 1905. In his mind, two mistakes committed by the Commune stood out above all others; as he declared in an often quoted article written on the anniversary of March 18th, in 1908:

The proletariat stopped half-way; instead of proceeding with the ‘expropriation of the expropriators’, it was carried away by dreams of establishing supreme justice in the country… institutions such as the Bank were not seized…. The second error was the unnecessary magnanimity of the proletariat; instead of annihilating its enemies, it endeavoured to exercise moral influence on them; it did not attach the right value to the importance of purely military activity in civil war, and instead of crowning its victory in Paris by a determined advance on Versailles, it hesitated and gave time to the Versailles government to gather its dark forces….

When the moment came for the revolution for which his whole life had been a preparation, Lenin would not repeat the Commune’s ‘half-measures’ and ‘unnecessary magnanimity’. There could be no question of accepting, as the Commune had demonstrated, ‘the available ready machinery of the State’, and adapting it; everything had to be smashed and re-created in a new, proletarian image. To Lenin and his followers, the supreme lesson of the Commune was that the only way to succeed was by total ruthlessness.

On the outbreak of the First World War, Lenin declared (on November 1st, 1914), ‘The transformation of the present imperialist war into a civil war is the only effective slogan of the proletariat, indicated by the experience of the Paris Commune….’ This was his objective throughout the war. When on the eve of success he was forced to flee briefly to Finland, Marx’s

The Civil War in France

was one of the two books he took with him on his final exile. When he returned, it was to impose Communism upon Russia by means of a revolution that never would have succeeded had it not been for the ‘dummy run’ attempted by Delescluze and his martyrs; and to impose it by resorting to ruthlessness with a flavour that also had its origins in those savage days. Lenin appears to have been constantly obsessed with fears that the October Revolution would go the way of the Comune; each day that it outlived the Commune, he is said to have counted ‘Commune plus one’. To ensure that the revolution would not be frittered away by the paralysing squabbles such as had arisen within so feebly democratic a body as the Commune, Lenin split with his more moderate allies, the Mcnsheviks; then proceeded remorselessly to crush the left-wing Constituent Assembly, until the extreme Bolshevik dictatorship was complete. ‘The Commune was lost,’ explained Lenin, ‘because it compromised and reconciled.’ His Red Army commissar, Trotsky, criticized the Commune for not meeting the ‘white terror of the bourgeoisie with the red terror of the proletariat’, and when civil war broke out in Russia neither Trotsky nor Lenin was backward in the dispensation of terror. How much

of the ferocious brutality with which the Russian Reds fought for survival was attributable to the ever-present memory of May 1871, may be judged by the comment in retrospect of an old Bolshevik:

In those grave moments we said; ‘Look, workers, at the example of the Paris Communards and know that if we are defeated, our bourgeoisie will treat us a hundred times worse.’ The example of the Paris Commune inspired us and we were victorious.

When Lenin died, his body was appropriately shrouded in a Communard flag, and his mantle passed to Stalin. Stalin once described the Commune as ‘an incomplete and fragile dictatorship’, a charge which he made sure would never be levelled against his tenancy of the Kremlin. If the course run by the Commune could perhaps be held responsible for contributing to the oppressively monolithic character assumed by the Bolshevist regime in Russia, well might one also speculate as to how much Stalin, when deciding on the wholesale liquidation of those Communists whose views in any way diverged from his own, had at the back of his mind the lessons of the destructive discord created by Pyat and the wranglers at the Hôtel de Ville.

In perhaps the most eloquent epitaph on the Communards ever uttered by a non-Marxist, Auguste Renoir (who so narrowly escaped with his life in those days) said of them:

They were madmen; but they had in them that little flame which never dies.

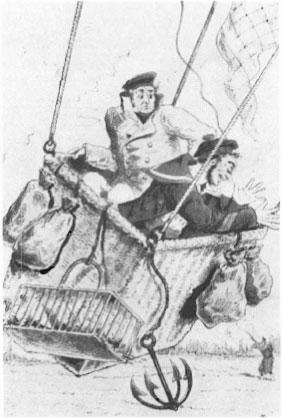

The memory of Louis-Napoleon’s glittering masked balls at the vanished Tuileries has been swallowed up by the mists of the past; little enough is still recalled about Trochu’s spiritless defence of Paris; and in France even the humiliation at Bismarck’s hands is largely forgotten. But the ‘little flame’ of the Communards continues to be kept alight. The link between the brave balloonists of Paris and the spacemen of ninety-five years later may seem a tenuous one. But the course of history often flows down strange and unexpected channels. In 1964, when the first three-man team of Soviet cosmonauts went up in the

Voskhod

, they took with them into space three sacred relics; a picture of Marx, a picture of Lenin—and a ribbon off a Communard flag.

Louis-Napoleon, on his return from Germany, 1871

General Trochu

General Ducrot

Léon Gambetta

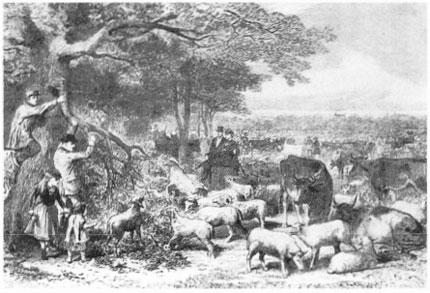

Cattle and the sheep in the Bois de Boulogne just before the Siege

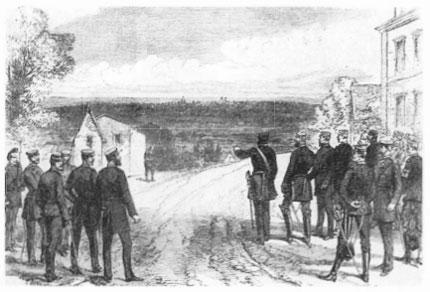

The Crown Prince of Prussia views Paris from the heights of Châtillon

‘How one could have used the balloons to surprise the enemy.’—From a drawing by Cham

‘My passport? Here it is!’—From

Souvenirs du Siège de Paris