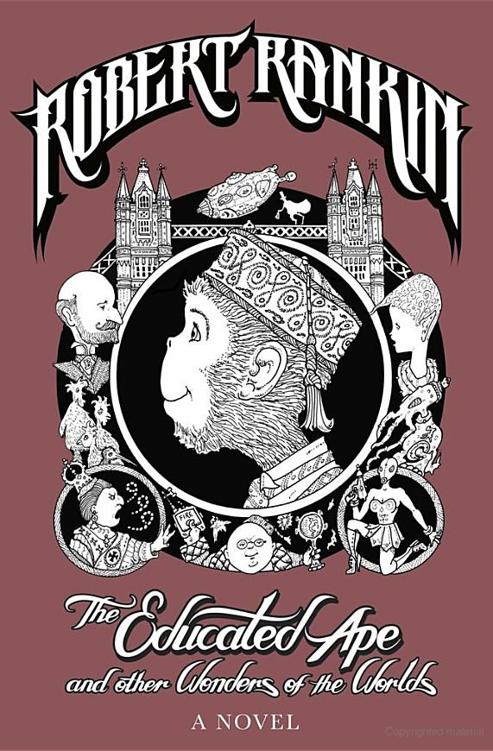

The Educated Ape & other Wonders of the Worlds

The Educated Ape

and other Wonders

of the Worlds

Robert Rankin

with illustrations by the author

Copyright © Robert Rankin 2012

All rights reserved

The right of Robert Rankin to be

identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in Great Britain in 2012

by Gollancz An imprint of the Orion Publishing Group

Orion House, 5 Upper St Martin’s Lane,

London WC2H 9EA An Hachette UK Company

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

ISBN (Cased) 978 0 575 08641 8

ISBN (Export Trade Paperback) 978 0 575

08642 5

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset at The Spartan Press Ltd,

Lymington, Hants

Printed and hound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd,

Croydon, CR0 4YY

The Orion Publishing Group’s policy is

to use papers that are natural, renewable and recyclable products and made from

wood grown in sustainable forests. The logging and manufacturing processes are

expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

THIS BOOK IS

DEDICATED TO

FIELD COURT ACADEMY

YEAR FIVE

2010—2011

YOU WERE SO MUCH FUN

TO BE WITH

‘So little of what could happen, does

happen.’

Salvador Dali

‘History is not quite the way it was.’

Humphrey Banana

‘Joy, joy moves the wheels

In the universal time machine.’

Friedrich Schiller

‘Ode to Joy’, 1785

1889

1

he

he

Bananary at Syon House raised many a manicured eyebrow.

Although

it was in its way the very acme

of fin de siècle

modernity, it so

forcefully scorned the conventions of how a glass-house, intended for the

cultivation of tropical fruit,

should

look as to cause tender ladies to

reach for the smelling—salts.

Syon

House itself was an ancient pile, the work of Robert Adam, embodying those

classical features and delicate touches that define the English country house

to create a dwelling both noble and stately. A venerable residence all can

admire.

The

Bananary, however, was something completely different. It boldly bulged from

the rear of Syon House in an alarming fashion that troubled the hearts of those

who dared to venture within, or viewed it from what was considered to be a safe

distance.

The

geometry was deeply wrong, the shape beyond grotesque. For although wrought from

the traditional mediums of ironwork and glass, these materials had been

tortured into such weird and outré shapes and forms as beggared a sane

description. This was clearly not the work of Sir Joseph Paxton, whose genius

conceived the Crystal Palace. Nor was it that of Señor Voice, the London tram

conductor turned architect whose radical confections were currently making him

the toast of the town, and whose bagnio in Baker Street had been showered with

awards by the Royal Institute of British Architects. The Bananary at Syon House

left most folk lost for words.

One

gentleman who was rarely lost for words was the Society Columnist of

The

Times

newspaper. He had recently visited Syon House to conduct an interview

with its owner Lord Brentford. His lordship had, four years earlier, been

pronounced ‘lost, believed dead’, having gone down, as it were, on the

Empress

of Mars

when she crashed into a distant ocean upon her maiden voyage. His

apparent return from the dead had caused quite a sensation in the British

Empire’s capital. His horror at the Bananary, built in his absence and adjoined

to the great house that was his by noble birth, had been — and still was —

profound.

The

Society Columnist of

The Times

had made a note of his lordship’s

quotable quotes.

‘If

this abomination is to be likened unto anything,’ Lord Brentford had fumed, ‘it

is a brazen blousy harlot who has unwelcomely attached herself to the

well—tailored coat of a distinguished elderly gentleman!’

‘What

manner of man,’ Lord Brentford further fumed, ‘could bring this blasphemy into

being?’

‘It

is —‘ and here he employed a phrase that would be reemployed many years later

by a prince amongst men ‘— a monstrous carbuncle upon the face of a much-loved

friend.’

It

would soon be torn down, Lord Brentford assured the Society Columnist, and he,

Lord Brentford, would dance upon the scattered ruins as one would upon the

grave of a conquered foe.

Strong

words!

Exactly

what the designer of the Bananary had to say about this was anybody’s guess.

But then he was

not

a reader of

The Times,

nor was he even a man.

He

had, however, been born upon Earth, unlike many who, upon this warm summer’s

evening, gaped open-jawed at the Bananary and thronged the electrically

illuminated gardens of Syon Park.

Fine

and well-laid gardens, these, if perhaps overly planted with tall banana trees.

The

moneyed and titled elite had come at Lord Brentford’s request to celebrate his

safe return and see him unveil his plans for a Grand Exposition: The Wonders of

the Worlds. His lordship had spent his years in forced exile planning this

extravaganza, and all, it was hoped, would soon be explained and revealed.

The

great and the good were gathered here.

The

rajahs and mandarins, princes and paladins,

Bankers

and barons and Lairds of Dunoon,

The

priest-kings and potentates, moguls of member states,

Even

the first man who walked on the Moon.

As

the Poetry Columnist of

The Times

so pleasantly put it.

Before

going on to put it some more for another twenty-seven verses.

Here

strolled emissaries and ecclesiastics from the planet Venus. Tall, imposing

creatures these, gaunt, high-cheekboned and elegant, with golden eyes and

elaborate coiffures. They gloried in robes of lustrous Venusian silks that swam

with spectrums whose colours had no names on Earth.

The

ecclesiastics were exotic beings of ethereal beauty who had about them a

quality of such erotic fascination that they all but mesmerised those men of

Earth with whom they deigned to speak. Although their femininity appeared unquestionable,

the nature of their sexuality had become the subject of both public debate and

private fantasy. It was popularly rumoured that they were tri-maphrodite, being

male and female and ‘of the spirit’, all in a single body. Nobody on Earth,

however, knew for certain.

The

ecclesiastics wore diaphanous gowns that afforded tantalising glimpses of

ambiguous

somethings

beneath. From their delicate fingers they swung

brazen censers upon long gilded chains, censers which this evening breathed

queer and haunting perfumes into an air already overburdened by the heady

fragrance of bananas.

The

Ambassador of Jupiter was also present. Typical of his race, he was a fellow

both hearty and rotund, given to immoderate laughter, extravagant gestures and

a carefree disposition that most who met him found appealing. His skin,

naturally grey as an elephant’s hide, was this evening toned a light pink in a

respectful mimicry of Englishness. His deep-throated chucklings rattled the

upper panes of the Bananary, eliciting fears of imminent collapse from the

faint-hearted but further mirth from himself and his Jovian entourage.

It

was difficult not to like the Jovians. For although tensions between the three

inhabited planets of this solar system — Venus, Jupiter and Earth — were

oft-times somewhat strained, the jovial Jovians found greater favour amongst

Londoners than the aloof and mysterious visitors from Venus.

Although

there was that certain

something

about the ecclesiastics …

There

were, of course, no Martians present at this glamorous soirée, for the Martian

race was happily extinct!

The

story of how this came about was known, in part, to almost every child in

England, told as a bedtime tale to put them soundly asleep.

‘Once

upon a time,’ so they were told, ‘in the year eighteen eighty-five, Phnaarg,

the evil King of Mars, declared war upon Earth and sent a mighty fleet of

spaceships to attack the British Empire. These fearsome warships landed in

Surrey and from them came terrible three-legged engines of death. The soldiers

of the Crown fought bravely but could not best the Martians, who employed most

wicked and ungentlemanly weapons against them. All would have been lost if not

for patriotic bacteria in the service of Her Majesty the Queen, God bless her,

which bravely killed the horrid invaders, and everyone lived happily ever

after. Now go to sleep or I will give you a smack.’

Which

was all well and good.

There

was, however, a second half to this tale, but few were the children who ever

heard it.

‘To

avoid the risk of further Martian attacks,’ so the unheard half goes, ‘Mr

Winston Churchill took control of the situation and formulated a top—secret

plan. With the aid of senior boffins Lord Charles Babbage and Lord Nikola

Tesla, several of the abandoned Martian spaceships were converted for human

piloting. They were then passengered by the incurables from the isolation

hospitals of the Home Counties and dispatched to the Red Planet. It was

effectively the birth of germ warfare, and it put paid to all the Martians of

Mars.

‘Thus

the British Empire encompassed another world and Queen Victoria became Empress

of both India and Mars. With the evil Martians now defeated, other inhabitants

of the solar system came forward to establish friendly relations with Earth,

which then joined Jupiter and Venus to form a family of planets.