The Deserters: A Hidden History of World War II (48 page)

Read The Deserters: A Hidden History of World War II Online

Authors: Charles Glass

John Bain at fourteen, the age at which he boxed in the finals of the Schoolboy Championships of Great Britain.

John Bain, of the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, in 1940, before his transfer to the Gordon Highlanders, the regiment from which he deserted.

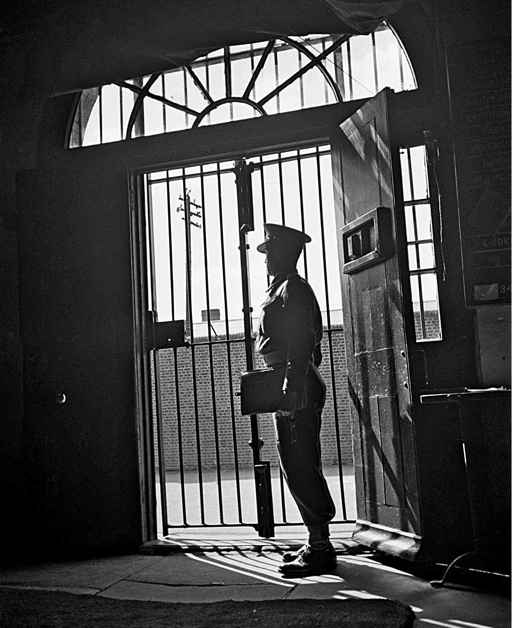

Although Bain did not serve time there, the Military Detention Barracks at Aldershot was the archetypal British military prison. Its nickname, the “glasshouse,” which derived from its roof, came to stand for any military prison.

GETTY IMAGES

Experimental medical equipment being used to treat British First World War soldiers suffering from shell shock.

Fortune

magazine reported in 1934 that “twenty-five years after the end of the last war, nearly half of the 67,000 beds in Veterans Administration hospitals [in the United States] are still occupied by the neuropsychiatric casualties of World War I.”

GETTY IMAGES

By the Second World War, at least some commanders favored providing psychiatric care in forward aid stations, which is where this U.S. soldier, here being administered a sedative, was sent.

GETTY IMAGES

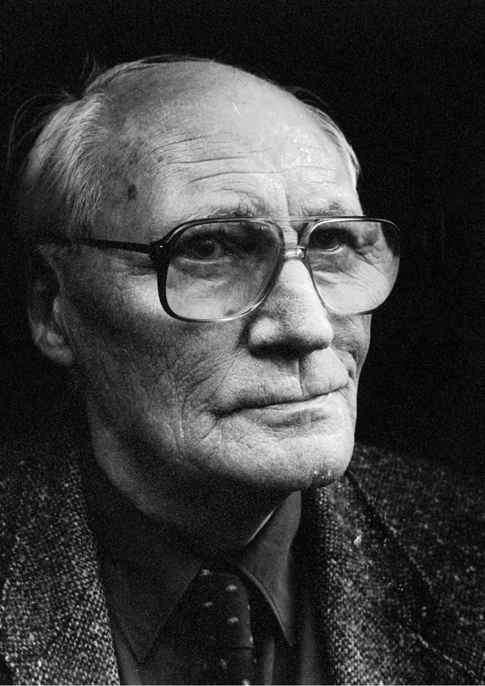

The artillery barrage at El Alamein inspired John Bain’s poem “Baptism of Fire” (published under his adopted name of Vernon Scannell): “And, with the flashes, swollen thunder roars / as, from behind, the barrage of big guns / begins to batter credence with its din / and, overhead, death whinnies for its feed . . .” Scannell was fortunate (or claimed to be), and was able to tell his son in a poem that “my spirit, underneath, / Survived it all intact.” He died in 2007, aged eighty-five.

THE ART ARCHIVE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M

Y LAST BOOK

,

Americans in Paris: Life and Death Under Nazi Occupation

, dealt with expatriates who stayed in wartime Europe when wisdom seemed to dictate departure. While I was writing their story, a young woman who was then living with one of my sons asked about people who fled. Did I know whether many American and British soldiers had deserted during the Second World War? I didn’t, and I soon discovered that not many other people did either. Much had been written about military deserters during the First World War, creating a body of literature that contributed to the campaign for their posthumous exoneration. My research into the subject of American, British and Commonwealth Second World War deserters turned up surprisingly few books that mentioned them. William Bradford Huie’s 1954

The Execution of Private Slovik

was almost the only lengthy discussion of the subject, although it focused on the one man who was executed rather than the 150,000 or so who survived.

Desertion by the men of the “Greatest Generation” remained for the most part taboo. Their stories lay in archives, police files, psychiatric reports and court-martial records. To uncover so much material and to explore an underexposed subject required considerable help, and the assistance afforded me in various and disparate quarters deserves more gratitude than I am able to express here.

I hereby thank Charlotte Goldsmith for asking the question about deserters that initiated this exploration. I must also thank my friends Goldie Hawn and Kurt Russell, who over wine on a restaurant terrace in Dubrovnik cut short my indecision over the book’s title by asking why I did not call it simply

Deserter

. While I was writing this book, a son, Lucien Christian Charles, was born to me and his mother, Anne Laure Sol, in Paris. His birth provided added inspiration as I struggled to make sense of everything I learned while researching. My work meant neglecting him at a time I shouldn’t have, and I ask his forgiveness. My older children, stepchildren and grandchildren tolerated absences and moodiness, tolerance for which I owe them apologies as much as thanks.

I worked on the book for the most part in the United States, France and Britain, where a legion of friends, collaborators and colleagues provided support of all kinds. In the United States, I particularly want to thank Dr. Tim Nenninger and Richard Boylan of the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland; Mary B. Chapman, Jeffrey Todd, Lisa Thomas and Joanne P. Eldridge of the Clerk of Court’s Office, United States Army Legal Services Agency, Arlington, Virginia; Elizabeth L. Garver, French Collections Research Associate at the Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas at Austin; Austin researcher Wendy Hagenmeier; Paul B. Barton, director of Library and Archives, George C. Marshall Foundation; Colonel Lance A. Betros and Major Dwight Mears of the Department of History, U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York; also at West Point, Dr. Rajaa Chouairi; Cleve Barkley and the Friends of the Second Infantry Division; and the staffs of the U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, and the National Personnel Records Center. I could not have completed the book as it is without the valuable contributions of Abigail Napp, Cora Currier, Christopher and Jennifer Isham, Mary Alice Burke, Jim Gudmens, Tony Zuvich, Jeff and Anne Price, Dr. Conrad C. Crane, Dr. Richard W. Stewart, Dr. David W. Hogan, Don Prell, Joe Dillard and John Bailey.

In Britain, I must thank, first of all, Steve Weiss. In addition, I am grateful to John Scannell and his sister Jane Scannell for their time and support in helping me to understand their father, Vernon Scannell. Scannell’s friend Paul Trewhela provided me with valuable material and the introduction to the Scannell family. I must thank my fellow writers Brian Moynahan, Colin Smith, Artemis Cooper and Max Hastings for advice and background material on the war. Professor Hugh Cecil of Leeds University and Cathy Pugh of the Second World War Experience Centre gave me valuable recorded interviews with British soldiers who recalled the deserters with whom they served during the war. I must also thank Anya Hart Dyke and Andrew Parsons; Verity Andrews and Nancy Fulford of the University of Reading Special Collections Service; and the staffs of the London Library, the National Archives at Kew, the British Library, the Liddell Hart Centre for Military Archives at King’s College London and the Imperial War Museum.

In France, where I wrote most of the book, my thanks must go to Lauren Goldenberg, Amy Sweeney, Charles Trueheart of the American Library in Paris, Alexandra Schwartz, Rose Foran, Alice Kaplan, Selwa Bourji, Stéphane Meulleau, Hildi Santo Tomas, Gil Donaldson, Sylvia Whitman and Jemma Birrell of Shakespeare and Company Bookshop and the staffs of the Archives Nationales de France, the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Musée des Collections Historiques de la Préfecture de Police de Paris. Acknowledgment must be made and praise given to the men and women who own and work at some of my favorite cafés in southern France: Café de l’Hôtel de Ville in Forcalquier, Les Terraces in Bonnieux, Café de France in Lacoste, Chez Claudette in Saint-Romain and the Café du Cours in Reillanne—ideal locales for writing, editing and daydreaming over coffee and tobacco.

I should also like to thank those who kindly offered me refuge from the distractions of urban life: the trustees and staff of the Lacoste campus of the Savannah College of Art and Design, who generously appointed me writer-in-residence during the hot summer of 2010; the music conductor Oliver Gilmour, for lending me his luxurious house in Dubrovnik; Roby and Kathy Burke, whose villa in Haute Provence could not have been bettered for tranquility and beauty in which to work; Taki and Alexandra Theorodarcopulos, in Gstaad; Simon and Ellie Gaul, for a room in their spectacular spread beside Grimaud; and Emma Soames, for the loan of her country house in southern France as the ideal setting in which to complete the work. My thanks also to Daniel and Véronique Adel for helping me find a house to rent not far from theirs in the Luberon.

Much gratitude must go to my editors, Ann Godoff at Penguin Press in New York and Martin Redfern at Harper Press in London. Their guiding hands (and spirits) are evident on every page. If any names are left out of this list, it is not intentional.