The Deserters: A Hidden History of World War II (46 page)

Read The Deserters: A Hidden History of World War II Online

Authors: Charles Glass

By the time of our promenade in Bruyères that balmy April afternoon, Weiss was in a better mood. We knocked on the doors of old people who were children in 1944 to ask if they knew where the 36th Division headquarters had been. No one was sure. One prim, white-haired matron in a cotton dress wondered why we wanted to know. When we told her that Steve had been a GI in the 36th Infantry Division, she threw out her arms. She was fourteen when they liberated the town from the

Boche

, she said, too young to kiss a GI. Now, she kissed Steve on both cheeks. Then she sobbed.

A little later, I suggested to him that his desertion might have saved him from an early death or a serious wound. But there were wounds. He said, “Look what I had to do to get right again. I spent years on the psychiatrist’s couch. I became a psychologist because of it, in terms of the war. I had to put the whole thing back together again.”

Weiss remembered a compound that included a headquarters building, a stockade and a chapel, where his trial took place. In 1944, winter snow veiled the town. The spring of 2011 was clear, almost hot. Townspeople directed us to several building complexes, where they thought the 36th might have made its headquarters. One was a large Catholic school attached to a stone chapel. Another was the local hospital, whose chapel was just outside the main building. Weiss stared at them in turn, walked around them and concluded that his normally letter-perfect memory just was not up to it. It did not matter. He had fought in Italy and France, won medals, deserted and been convicted somewhere in this Vosges village. He had served time in the Loire Disciplinary Training Center and in the confines of his memory, where the trial was reenacted for years. Finding the former courtroom was, anyway, something I had asked him to do. I thought it might bring out elements of his story that were not in the official transcript. If the room where the court-martial took place on 7 November 1944 was a key, we didn’t find it.

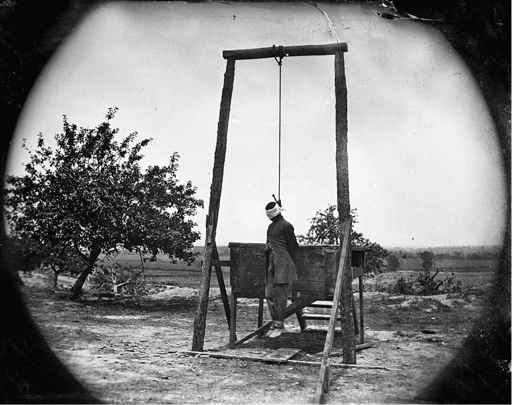

William Johnson, an African-American soldier in the Union Army, hanged for desertion and “an attempt to outrage the person of a young lady” in June 1864.

EVERETT COLLECTION/REX FEATURES

A little over a year later, in October 1865, William Smitz became the last U.S. soldier to be executed for desertion until Private Eddie Slovik (above) was shot by firing squad on 31 January 1945. Of the 150,000 British and U.S. soldiers who deserted during the Second World War, Slovik was the only one executed for it.

BETTMAN/CORBIS

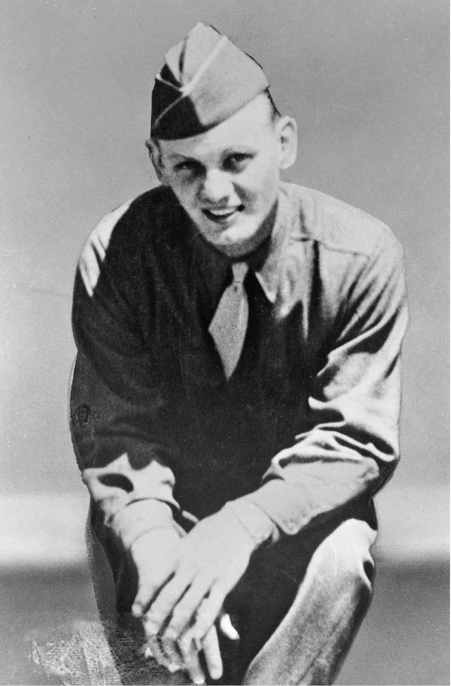

A young Private Steve Weiss (on the left in both photographs) at the Infantry Replacement Training Center at Fort Blanding, Florida, in late 1943.

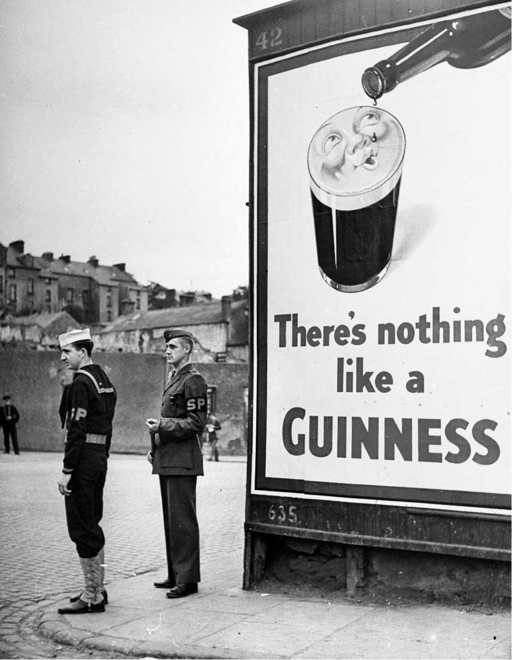

U.S. Navy and Marine Shore Patrolmen at a railway station near a U.S. naval operations base in the United Kingdom to prevent U.S. servicemen going AWOL.

TIME & LIFE PICTURES/GETTY IMAGES

In the run-up to D-Day, military and civilian police rounded up U.S. soldiers in London whose papers were not in order.

ANTHONY WALLACE/DAILY MAIL/REX FEATURES

Official U.S. Army photograph, taken at Pozzuoli near Naples in August 1944, that happened to capture Private First Class Steve Weiss boarding a British landing craft. He is climbing the gangplank on the right-hand side of the photograph.

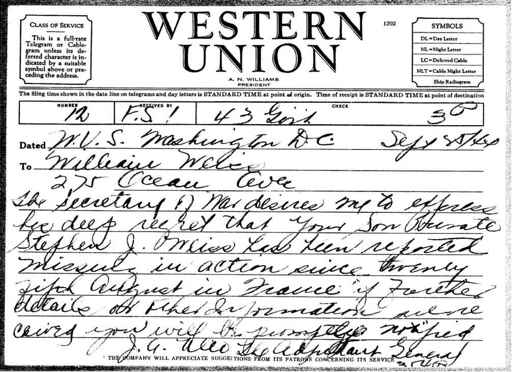

Telegram received by William Weiss on 25 September 1944: “The Secretary of War desires me to express his deep regret that your son Private Stephen J. Weiss has been reported missing in action . . .”

Steve Weiss’s rifle squad in the Vosges, October 1944. Weiss is standing, second from left, and to his left are, in turn, Dickson, Reigle and Gualandi; kneeling left is Fawcett.

In Alboussière, Steve Weiss refused to join the firing squad that executed a Vichy

milicien

. The photograph above is of the execution of six members of the Milice that was witnessed by CBS correspondent Eric Sevareid in Grenoble.