The Dawn of Innovation (29 page)

Read The Dawn of Innovation Online

Authors: Charles R. Morris

They “reached the ground about an hour before midnight,” parked their carriage in care of a servant, and made their way through three circles of fire and tents. There were fifteen preachers in attendance; they would preach in rotation from Tuesday through Saturday. No one was preaching outside when Trollope and her party arrived, but “discordant, harsh, and unnatural” sounds were coming from the tents. They entered one and saw “a tall grim figure in black . . . uttering with incredible vehemence an oration that seemed to hover between praying and preaching.” The circle of people kneeling around him responded with “sobs, groans, and a sort of low howling inexpressibly painful to listen to.”

“At midnight a horn sounded through the camp,” and people flocked from all over to the central preacher's stand. Trollope and her hosts estimated that there were about 2,000 people in attendance, and they found a place right next to the preacher's stand. A space in front of the stand was called “the pen,” and after a harangue that “assured us of the enormous depravity of man,” one of the preachers invited “anxious sinners” who wished “to wrestle with the Lord to come forward into the pen.”

ay

ay

When few people moved to come up, the preachers came down to the pen and began to sing a hymn.

As they sung they kept turning themselves round to every part of the crowd, and by degrees, the voices of the whole multitude joined in chorus. This was the only moment at which I perceived any thing like the solemn and beautiful effect, which I had heard ascribed to this woodland

worship. It is certain that the combined voices of such a multitude, heard at dead of night, from the depths of their eternal forests, the many fair young faces turned upward, and looking paler and lovelier as they met the moon-beams, the dark figures in the middle of the circle, the lurid glare thrown by the altar-fires on the woods beyond, did altogether produce a fine and solemn effect, that I shall not easily forget.

worship. It is certain that the combined voices of such a multitude, heard at dead of night, from the depths of their eternal forests, the many fair young faces turned upward, and looking paler and lovelier as they met the moon-beams, the dark figures in the middle of the circle, the lurid glare thrown by the altar-fires on the woods beyond, did altogether produce a fine and solemn effect, that I shall not easily forget.

But soon the “sublimity gave way to horror and disgust,” as Trollope was fascinated and repelled by the undertone of sexuality:

Above a hundred persons, nearly all females, came forward, uttering howlings and groanings, so terrible that I shall never cease to shudder when I recall them . . . and they were all soon lying on the ground in an indescribable confusion of heads and legs. They threw about their limbs with such incessant and violent motion, that I was every instant expecting some serious accident to occur....

Many of these wretched creatures were beautiful young females. The preachers moved among them, at once exciting and soothing their agonies. I heard the muttered “Sister! dear sister!” I saw the insidious lips approach the cheeks of the unhappy girls; I heard the murmured confessions of the poor victims, and I watched their tormentors, breathing into their ears consolations that tinged the pale cheek with red.... I do [not] believe that such a scene could have been acted in the presence of Englishmen without instant punishment being inflicted.

Eventually, “the atrocious wickedness of this horrible scene increased to a degree of grossness, that drove us from our station.” Trollope and her friends repaired to their carriage to snatch some sleep (on beds prepared by the servant) and “passed the remainder of the night in listening to the ever increasing tumult at the pen.”

But as morning broke, the show-business aspect of it all began to dawn:

The Coming of the RailroadsThe horn sounded again, to send them to private devotion; and about an hour afterward I saw the whole camp as joyously and eagerly employed in preparing and devouring their most substantial breakfasts as if the night had been passed in dancing; and I marked many a fair but pale face, that I recognized as a demoniac of the night, simpering beside a swain to whom she carefully administered hot coffee and eggs....

After enjoying an abundance of strong tea, which proved a delightful restorative after a night so strangely spent, I wandered alone into the forest, and I never remember to have found perfect quiet more delightful.

Â

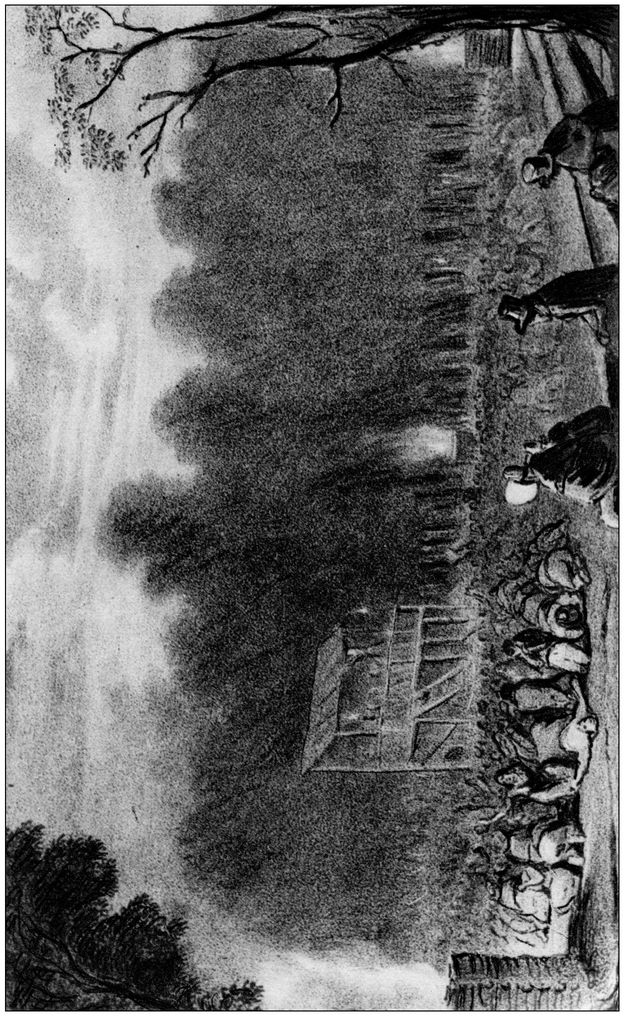

Trollope camp meeting.

Lithograph by August hervieu .Trollope is in the foreground (with illuminated bonnet). Hervieu is behind her with his sketch pad. Note the discreet distance maintained by trollope's entourage from the scene before them.

43

Lithograph by August hervieu .Trollope is in the foreground (with illuminated bonnet). Hervieu is behind her with his sketch pad. Note the discreet distance maintained by trollope's entourage from the scene before them.

43

Steamboats did an effective job of tying together the interior of the country west of the Alleghanies, but as the Erie Canal had shown, the real bonanzas came from linking the West with the eastern seaboard. Chicago, Cleveland, and New York could be linked by water, but common-carrier transportation from interior cities like Pittsburgh and Baltimore would have to cross some formidable mountains; all skeptics notwithstanding, that required railroads.

Canals and railroads are both forms of low-friction transportation and were much in competition in the first third or so of the nineteenth century. “Low-friction” also includes horse-drawn trolleys, which were common in nineteenth-century cities. One of the earliest of commercial railroads, the Baltimore & Ohio (B&O), was horse-drawn during its first couple years of operation but switched to steam in 1830. The cost and difficulty of constructing canals and railroads were not greatly different,

az

44

but railroads were generally much faster and therefore came to be preferred by passengers.

az

44

but railroads were generally much faster and therefore came to be preferred by passengers.

Great Britain had used steam locomotives in mines from the early 1800s, but the two countries got off to a roughly neck-and-neck start in commercial railroads. George Stephenson opened the first commercial British railroad, the Stockton and Darlington, in 1825. The first commercial steam railroad in the United States commenced operating either in 1828 or 1829. The first American railroad entrepreneurs bought their engines from Great Britain, but British engines were designed for the highly engineered British rail system, with its heavy tracks, level runs, and minimal curves. They destroyed American tracks and were easily derailed.

45

Robert L. Stevens, head of the Camden and Amboy, invented the T-rail, which still prevails today. It's easy to lay and very durable. A New York engineer, John Jervis, invented the rail-hugging swivel carriage for the front of the locomotive. Even in the mid-1830s, Jervis's engines could routinely hit sixty miles per hour. Also by then, American locomotives had acquired their bell-shaped stacksâto reduce the flying sparks from wood-fueled enginesâand the cowcatchers, which allowed killing a cow without a derailment. They were also the first to incorporate lightingâat first just a fire-bearing cart pushed in front, later replaced by a kerosene lamp with a mirror to project a beam.

46

45

Robert L. Stevens, head of the Camden and Amboy, invented the T-rail, which still prevails today. It's easy to lay and very durable. A New York engineer, John Jervis, invented the rail-hugging swivel carriage for the front of the locomotive. Even in the mid-1830s, Jervis's engines could routinely hit sixty miles per hour. Also by then, American locomotives had acquired their bell-shaped stacksâto reduce the flying sparks from wood-fueled enginesâand the cowcatchers, which allowed killing a cow without a derailment. They were also the first to incorporate lightingâat first just a fire-bearing cart pushed in front, later replaced by a kerosene lamp with a mirror to project a beam.

46

Â

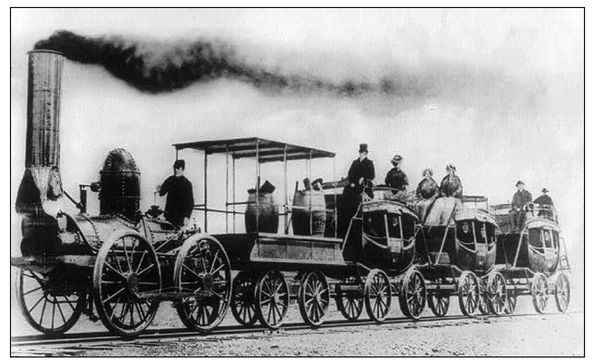

The deWitt Clinton Locomotive.

The

deWitt Clinton

was the first steam locomotive to run in New York state, in 1831, on the Mohawk and Hudson line between Albany and Schenectady, a run of sixteen miles.

The

deWitt Clinton

was the first steam locomotive to run in New York state, in 1831, on the Mohawk and Hudson line between Albany and Schenectady, a run of sixteen miles.

Harriet Martineau traveled by one of the first train lines in the South. She took an overnight stage to Columbia, some sixty miles, to meet a train

due to arrive at eleven the next morning, which would take her to Charleston, another sixty-two miles, in time for dinner. The carriage hit a stump and was very late, but the train had had its own minor accident and was even later, so the passengers still had a several-hour wait. Martineau wrote:

due to arrive at eleven the next morning, which would take her to Charleston, another sixty-two miles, in time for dinner. The carriage hit a stump and was very late, but the train had had its own minor accident and was even later, so the passengers still had a several-hour wait. Martineau wrote:

I never saw an economical work of art harmonize so well with the vastness of a natural scene. From the piazza [where they were waiting] the forest fills the whole scene, with the railroad stretching through it, in a perfectly straight line, to the vanishing point. The approaching train cannot be seen so far off as this. When it appears, a black dot marked by its wreath of smoke, it is impossible to avoid watching it, growing and self-moving, till it stops before the door....

For the first thirty-five miles, which we accomplished by half-past four, we called it the most interesting rail-road we had ever been on. The whole sixty-two miles was almost a dead level, the descent being only two feet. Where pools, creeks, and gullies had to be passed, the road was elevated on piles, and thence the look down on an expanse of evergreens was beautiful....

At half-past four, our boiler sprang a leak, and there was an end to our prosperity. In two hours, we hungry passengers were consoled with the news that it was mended. But the same thing happened again and again; and always in the middle of a swamp, where we could do nothing but sit still....

After many times stopping and proceeding, we arrived at Charleston between four and five in the morning; and it being too early to disturb our friends, crept cold and weary to bed, at the Planter's Hotel.

47

47

Despite a wild English railroad-building bubble in 1845â1848, the United States quickly outstripped the United Kingdom in total rail mileage.

The construction boom of the 1850s was nothing short of stupendous. Mileage increased by half in New England, doubled in the Middle Atlantic states, quadrupled in the South, and increased eightfold in the West. By 1860, the West was becoming the center of gravity of the national population and had the greatest extent of railroad mileage. Locomotives got much bigger, faster, and more complex, while bridge builders like John Roebling achieved new milestones in suspension bridge technology, as in his Niagara River Suspension Bridge connecting the United States and Canada, which was opened to train traffic in 1855.

| Railroad Miles in Service 48 | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | United Kingdom | United States |

| 1840 | 1,650 | 2,760 |

| 1850 | 6,100 | 8,600 |

| 1860 | 9,100 | 28,900 |

A concerted national program of internal improvements, with a heavy focus on transportation to knit the country together, had long been the dream of Henry Clay and the Whigs. Jefferson himself had favored turnpike and canal building, but Andrew Jackson had put an effective end to federally supported internal improvements with a famous 1830 veto, incidentally foregoing the opportunity to establish national standards for items like road gauges (track widths) to ensure connectivity.

49

49

Trollope visited Washington as the debate over internal improvements was at its zenith, and attended several of the debates: “I do not pretend to judge the merits of the question. I speak solely of the singular effect of seeing man after man start eagerly to his feet, to declare that the greatest injury, the basest injustice, the most obnoxious tyranny that could be practised against the state of which he was a member, would be the vote of a few million dollars for the purpose of making their roads or canals; or for drainage; or, in short, for any purpose of improvement whatsoever.” A few days later, she witnessed the elaborate funeral cortege of a deceased congressman and learned that all members were entitled to be “buried at the expense of the government (this ceremony not coming under the head of internal improvement).”

50

50

The practical effect of the improvements veto was that extensive development of the roads was almost always a combined public-private enterprise, with private investors contributing equity, while the states sold

revenue bonds and facilitated the assemblage of the necessary rights-of-way. One of the most ambitious of the early projects was a hybrid Philadelphia-Pittsburgh connection largely financed by the state of Pennsylvania and comprising canals on either side of the Alleghanies, with a “Portage Railroad” to cross the mountains. When it opened in 1834, a traveler could board a train in Philadelphia and proceed 82 miles by rail to Columbia, on the Susquehanna River; shift to a canal boat for 176 miles to Hollidaysburg, near Altoona; then cross the Alleghanies to Johnstown via a series of wooden inclined planes, with an average slope of about 10 percent. The distance of the traverse was 36 miles as the crow flies, with railcars pulled up by stationary steam engines on the ascent and coasting free on the downslope. Johnstown was the terminus for a final 104-mile canal connection directly into Pittsburgh. The highest point on the Portage road was 2,300 feet above sea level, and the vertical distance of the ascent and descent on the inclined planes were 1,100 and 1,300 feet respectively.

51

revenue bonds and facilitated the assemblage of the necessary rights-of-way. One of the most ambitious of the early projects was a hybrid Philadelphia-Pittsburgh connection largely financed by the state of Pennsylvania and comprising canals on either side of the Alleghanies, with a “Portage Railroad” to cross the mountains. When it opened in 1834, a traveler could board a train in Philadelphia and proceed 82 miles by rail to Columbia, on the Susquehanna River; shift to a canal boat for 176 miles to Hollidaysburg, near Altoona; then cross the Alleghanies to Johnstown via a series of wooden inclined planes, with an average slope of about 10 percent. The distance of the traverse was 36 miles as the crow flies, with railcars pulled up by stationary steam engines on the ascent and coasting free on the downslope. Johnstown was the terminus for a final 104-mile canal connection directly into Pittsburgh. The highest point on the Portage road was 2,300 feet above sea level, and the vertical distance of the ascent and descent on the inclined planes were 1,100 and 1,300 feet respectively.

51

Other books

Empire of Dust by Williamson, Chet

Sisters Grimm 05 Magic and Other Misdemeanors by Michael Buckley

Gregory's Rebellion by Lavinia Lewis

A Dream of Daring by LaGreca, Gen

Turned by Kessie Carroll

Scarlet by A.C. Gaughen

Suddenly Married by Loree Lough

Highland Daydreams by April Holthaus

Biker Justice: A Skull Kings MC Novella by Sage L. Morgan

Immortal Heat (The Guardians of Dacia Book 1) by Loni Lynne