The Dawn of Innovation (13 page)

Read The Dawn of Innovation Online

Authors: Charles R. Morris

The industrial historian Carolyn Cooper has matched machine descriptions to the still-extant belting shafts and pulleys and still-visible floor markings in the factory, and mined old documents and Brunel's notes and records to reconstruct the factory's output, layout, and processing flows.

The flow process was clearly thought through with careâwhich was unusual in that period, even in the much-touted American armories. Work in process was moved from station to station in wheeled bins. Output was high: the large mortise chisels ran at a hundred strokes per minute, and the blocks were advanced

of an inch at each stroke. One man could bore and mortise 500 6-inch or 120 16-inch single-sheaved blocks in eleven and a half hoursâthat's two operations in about a minute and a half for the smaller blocks, and in less than six minutes for the larger ones. A figure widely quoted from Brunel's biographer, however, that 110 men had been replaced with only 10, should probably be taken with a grain of salt.

of an inch at each stroke. One man could bore and mortise 500 6-inch or 120 16-inch single-sheaved blocks in eleven and a half hoursâthat's two operations in about a minute and a half for the smaller blocks, and in less than six minutes for the larger ones. A figure widely quoted from Brunel's biographer, however, that 110 men had been replaced with only 10, should probably be taken with a grain of salt.

r

of an inch at each stroke. One man could bore and mortise 500 6-inch or 120 16-inch single-sheaved blocks in eleven and a half hoursâthat's two operations in about a minute and a half for the smaller blocks, and in less than six minutes for the larger ones. A figure widely quoted from Brunel's biographer, however, that 110 men had been replaced with only 10, should probably be taken with a grain of salt.

of an inch at each stroke. One man could bore and mortise 500 6-inch or 120 16-inch single-sheaved blocks in eleven and a half hoursâthat's two operations in about a minute and a half for the smaller blocks, and in less than six minutes for the larger ones. A figure widely quoted from Brunel's biographer, however, that 110 men had been replaced with only 10, should probably be taken with a grain of salt.r

The best estimate for the cost savings comes from the payment to Brunel, which by contract was to be equal to the savings realized in the first year after the plant achieved full operationsâa very Benthamite arrangement, for brother Jeremy had long advocated for government performance contracting. The actual payment award was £17,000, based on 1808 production of 130,000 blocks at a cost of £50,000, which suggests a 25 percent savings (17,000/[17,000 + 50,000]). That tracks well with a “generally accepted,” mid-nineteenth-century estimate reported by Cooper that the plant paid for itself within four years.

44

All in all, the venture must be considered a superb success, especially since the savings kept rolling in for many years after the investment was fully recovered.

44

All in all, the venture must be considered a superb success, especially since the savings kept rolling in for many years after the investment was fully recovered.

Bentham and Brunel, of course, were extremely proud of their plant, and the government was delighted for once to crow about its rigorous cost management. But as a torchlight pointing toward new directions in manufacturing, the Portsmouth plant utterly fizzled. The British trumpeted its virtues, tourists oohed and aahed their way through, but it made no impact on the style and methods of British industry. Cooper has unearthed possible half-hearted imitations here and there, but nothing important or lasting.

So we see the British intellectualizing their industrial accomplishments, complacent with their methods and processes, and through most of the nineteenth century oblivious to the empirical and often original approaches of the Americans.

That may be the fate of winners, for Americans made the same mistakes a century later. In the 1950s and 1960s, executive self-celebration was assiduously watered by business school professors, who had begun churning out students with master's degrees in business administration, trained mostly in blackboard-compatible topics like finance and organization. A complacent American corporate elite, ignorant of the shop floors in their own plants, were utterly oblivious to the storm that was about to be unleashed by the new plants, the new tools, and striking new approaches taken by waves of hungry new competitors, first from Germany and Japan, and then from nearly the whole of east and south Asia.

45

45

CHAPTER THREE

The Giant as Adolescent

HEZEKIEL NILES, THE PROPRIETOR OF

NILES WEEKLY REGISTER

, AMERICA'S first national newspaper, reported in October 1825:

NILES WEEKLY REGISTER

, AMERICA'S first national newspaper, reported in October 1825:

Wednesday last [October 26, 1825] was a great day in New York, the Erie Canal being completed. . . . The first gun, to announce the complete opening of the New York canal, was to be fired at Buffalo, on Wednesday last, at 10 o'clock precisely. . . . It was repeated, by heavy cannon stationed long the whole canal and river . . . and the gladsome sound reached the city of New York at 20 minutes past 11âwhen a grand salute was fired at fort Lafayette, and was reiterated back up to Buffalo. . . . The cannon . . . were some of those

Perry

had before used on Lake Erie, on the memorable 11th of September 1814.

Perry

had before used on Lake Erie, on the memorable 11th of September 1814.

The serious partying got under way when a flotilla of dignitaries actually arrived in the city ten days after embarking upon the canal at Buffalo. They were received “with thunders of artillery, and the acclamations of rejoicing scores of thousands.” Niles guessed that there were “some 30 to 50,000 strangers in New York” to watch deWitt Clinton pour a barrel of Lake Erie water into the Hudson.

The whole population of the city exerted itself to give brilliancy to the occasion. The various banners of different bodies, highly ornamented states, &c. presented a whole the like of which never has before been witnessed

in America. In the evening, some of the public buildings were illuminated, and there were balls and private parties, not to be counted.... The whole appears to have passed off without disturbance, except at Castle Garden, in which 4 or 5,000 people were assembled to witness the second ascension by Mad. Johnson, in a balloonâbut it would not rise with her; the people outside became very clamorous; and those within, at last, got impatient, and proceeded to tear the balloon into pieces and destroy the furniture within the walls, by way of satisfaction.

1

in America. In the evening, some of the public buildings were illuminated, and there were balls and private parties, not to be counted.... The whole appears to have passed off without disturbance, except at Castle Garden, in which 4 or 5,000 people were assembled to witness the second ascension by Mad. Johnson, in a balloonâbut it would not rise with her; the people outside became very clamorous; and those within, at last, got impatient, and proceeded to tear the balloon into pieces and destroy the furniture within the walls, by way of satisfaction.

1

The high spirits were fully justified, for it was hard to overestimate the importance of the Erie Canal. It welded the whole Northeast into a single economic unit, vaulting it, even in its still-primitive state, into the ranks of the world's largest economies.

Britons paid little attention to such developments. Rev. Sidney Smith, a canon of St. Paul and well-known man of letters, was speaking for the elite when he commented on an 1820 statistical review of the United States:

We are friends and admirers of Jonathan [“Brother Jonathan” was British slang for their bumptious transatlantic cousin]; But he must not grow vain and ambitious; or allow himself to grow dazzled . . . [by claims] that they are the greatest, the most refined, the most enlightened, and the most moral people upon earth.... The Americans are a brave, industrious, and acute people; but they have hitherto given no indication of genius, and have made no approach to the heroic.... Where are their Foxes, their Burkes, their Sheridans? . . .âWhere their Arkwrights, their Watts, their Davys. . . . Who drinks from American glasses? Or eats from their plates?

2

2

Through a European lens, in fact, America looked very backward, if only because of its overwhelmingly rural demography. In the 1820s, more than 90 percent of Americans still lived in the countryside, a pattern that had changed very little by mid-century.

3

In nineteenth-century Europe, rural areas were mostly peasant-ridden backwaters, but America's agrarian patina concealed a beehive of commercial and industrial activity. By the end of the War of 1812, Gordon Wood suggests, the northern states were possibly “the most thoroughly commercialized society in the world.” A Rhode Island industrialist made the same point in 1829: “The manufacturing activities of the United States are carried on in little hamlets . . . around the water fall which serves to turn the mill wheel.”

4

3

In nineteenth-century Europe, rural areas were mostly peasant-ridden backwaters, but America's agrarian patina concealed a beehive of commercial and industrial activity. By the end of the War of 1812, Gordon Wood suggests, the northern states were possibly “the most thoroughly commercialized society in the world.” A Rhode Island industrialist made the same point in 1829: “The manufacturing activities of the United States are carried on in little hamlets . . . around the water fall which serves to turn the mill wheel.”

4

Â

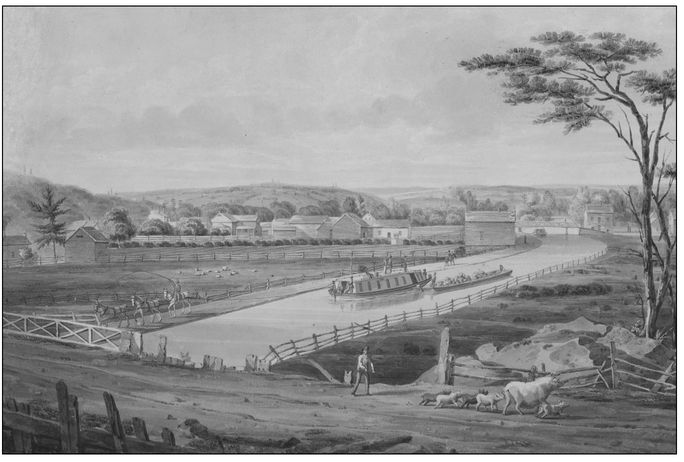

Erie Canal, 1830.

This bucolic scene would have been typical of virtually the entire route when the canal first opened. By connecting the port of New York City with the New York interior and all the territories bordering on the Great Lakes, it jump-started the commercialization of the entire region. Note the horse-drawn motive power.

This bucolic scene would have been typical of virtually the entire route when the canal first opened. By connecting the port of New York City with the New York interior and all the territories bordering on the Great Lakes, it jump-started the commercialization of the entire region. Note the horse-drawn motive power.

American historians have suffered their own bafflements. It is only in recent decades that a consensus of sorts has emerged on the nation's early growth spurt. Winifred Rothenberg did much of the groundbreaking workâtwenty-five years of patient excavation of the account books, diaries, estates, mortgages, and other records of Massachusetts farmers.

5

What she finds is an organic, bottom-up form of modernization, originating in the increasing prosperity of ordinary farmers. The British experience was starkly different. The underbelly of Victorian society mapped by Charles Dickens was a rural proletariat brutally expelled from the countryside and herded into urban factories.

5

What she finds is an organic, bottom-up form of modernization, originating in the increasing prosperity of ordinary farmers. The British experience was starkly different. The underbelly of Victorian society mapped by Charles Dickens was a rural proletariat brutally expelled from the countryside and herded into urban factories.

Many of Rothenberg's farmers were among their local elites, but outside of the South, American rural elites were decidedly middle-class, with modestly sized farms. During the immediate post-Revolutionary years, New England and Middle Atlantic farmers became strikingly more entrepreneurial. Farmers started making more frequent, and longer, marketing trips, evidencing a search for best-price markets. Those trips ceased abruptly in the 1820s, as thickening networks of local merchants made them unnecessary. Price disparities for crops or tools virtually disappeared over wide regions. That same market-driven behavior can be seen in farmers' own operations. Wage labor became a favored form of farm employment, with consistent skill-based wage rates. Farm surpluses were often invested in mercantile and industrial undertakings instead of land, and farmer's estates showed a clear trend toward financial instruments: mortgages, canal and bridge bonds, even company stock.

As the Erie Canal exposed Rothenberg's farmers to new competitive threats from larger-scale New York grain farms, they quickly shifted into labor-intensive, high-productivity lines like dairying and hay production. The timing of hog slaughtering suggests that farmers made sophisticated profit calculations: stretching out fattening periods when feed was cheap and meat was dear, and vice versa. All in all, it was a sharp departure from pre-Revolutionary behavior, when the forebears of these same farmers were far less experimental than the English in adopting new farming methods or searching for higher-return crops.

6

6

Local merchants often provided the impetus toward new enterprises. The Holleys of Salisbury, in the northwest corner of Connecticut, are a good example. The family was old farming stock who had been in western Connecticut for generations. Holley males were mostly farmers and ministers until Luther Holley opened a store and trading operation in the mid-eighteenth century. Salisbury also had good-quality iron deposits, and Luther traded iron from local smelters from the start.

A group that included Ethan Allen of Revolutionary War fame opened a blast furnace in 1762. Although the Allen group failed, subsequent owners prospered during the war, even casting cannons for the American

forces.

7

After the war, as the iron business went into decline, Luther started buying ironworking properties to lock up supply for his iron trading and by 1799 had the largest local holdings. He took in his son John as a partner, and when Luther retired in 1810, John formed a new partnership with another merchant and iron trader, John Coffing.

8

forces.

7

After the war, as the iron business went into decline, Luther started buying ironworking properties to lock up supply for his iron trading and by 1799 had the largest local holdings. He took in his son John as a partner, and when Luther retired in 1810, John formed a new partnership with another merchant and iron trader, John Coffing.

8

Neither Coffing nor John Holley considered themselves “iron men.” They were merchants who happened to trade their own iron and iron kettles, along with grains, liquors, cloth, and whatever else they could readily sell. But they had a good eye for talent and knew the top local artisans. During the War of 1812, they cast cannon and anchors for the navy, and they began making sales and lobbying forays to Washington. After the war, they become an important source of gun iron to the Springfield Armory and to contractors like Eli Whitney.

Other books

Blaggard's Moon by George Bryan Polivka

What We Find by Robyn Carr

Hillerman, Tony - [Leaphorn & Chee 01] by The Blessing Way (v1) [html, jpg]

World Made by Hand by James Howard Kunstler

Filling The Void by Allison Heather

The Seal Wife by Kathryn Harrison

The Billionaire Princess by Christina Tetreault

First Day On Earth by Castellucci, Cecil

Just a Little Embrace by Tracie Puckett

Myth Man by Mueck, Alex