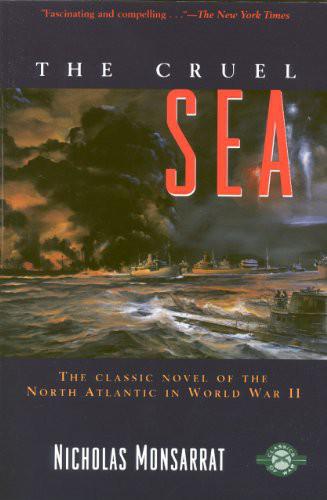

The Cruel Sea (1951)

| The Cruel Sea (1951) | |

| Monsarrat, Nicholas | |

| (1951) | |

| Tags: | WWII/Navel/Fiction WWII/Navel/Fictionttt |

A maritime adventure originally published in 1951. Set in the Second

World War, two ships and their crews of about a hundred and fifty men

are involved in defending Atlantic convoys against impossible odds.

- Copyright & Information

- About the Author

- Dedication

- Author's Note

- Before the Curtain

- PART ONE

- PART TWO

- PART THREE

- PART FOUR

- PART FIVE

- PART SIX

- PART SEVEN

- Synopses of Nicholas Monsarrat Titles

The Cruel Sea

First published in 1951

© Estate of Nicholas Monsarrat; House of Stratus 1951-2011

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise), without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

The right of Nicholas Monsarrat to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted.

This edition published in 2011 by House of Stratus, an imprint of

Stratus Books Ltd., Lisandra House, Fore Street, Looe,

Cornwall, PL13 1AD, UK.

Typeset by House of Stratus.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library and the Library of Congress.

| | | EAN | | ISBN | | Edition | | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| | | 0755131282 | | 9780755131280 | | Pdf | | |

| | | 0755131290 | | 9780755131297 | | Mobi/Kindle | | |

| | | 0755131304 | | 9780755131303 | | Epub | | |

This is a fictional work and all characters are drawn from the author's imagination.

Any resemblance or similarities to persons either living or dead are entirely coincidental.

www.houseofstratus.com

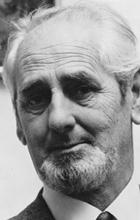

Nicholas Monsarrat

was born in Liverpool, the son of a distinguished surgeon. He was educated at Winchester and then at Trinity College, Cambridge where he studied law. However, his subsequent career as a solicitor encountered a swift end when he decided to leave Liverpool for London, with a half-finished manuscript under his arm and £40 in his pocket.

The first of his books to attract attention was the largely autobiographical ‘This is the Schoolroom’. It is a largely autobiographical 'coming of age' novel dealing with the end of college life, the 'Hungry Thirties', and the Spanish Civil War. During World War Two he joined the Royal Navy and served in corvettes. His war experience provided the framework for the novel ‘HMS Marlborough will enter Harbour’, and one of his best known books. ‘The Cruel Sea’ was made into a classic film starring Jack Hawkins. After the war he became a director of the UK Information Service, first in Johannesburg, then in Ottawa.

Established as a sort after writer who was also highly regarded by critics, Monsarrat’s career eventually concluded with his epic ‘The Master Mariner’, a novel on seafaring life from Napoleonic times to the present.

Well known for his concise story telling and tense narrative, he became one of the most successful novelists of the twentieth century, whose rich and varied collection bears the hallmarks of a truly gifted master of his craft.

‘A professional who gives us our money’s worth. The entertainment value is high’- Daily Telegraph

To:

Philippa Crosby

All the characters in this book are wholly fictitious. If I have inadvertently used the names of men who did in fact serve in the Atlantic during the war, I apologise to them for so doing. Where I have mentioned actual war appointments, such as Flag-Officer-in-Charge at Liverpool or Glasgow, the characters who are portrayed in such appointments have no connexion whatsoever with their actual incumbents; and if there

was

a W.R.N.S. officer holding the job of S.0.0.2 on the Clyde in 1943, then she is not my ‘Second Officer Hallam’. In particular, my Admiral in charge of the working-up base at ‘Ardnacraish’ is

not

intended as a portrait of the energetic and distinguished officer who discharged with such efficiency a similar task in the Western Approaches Command.

This is the story – the long and true story – of one ocean, two ships, and about a hundred and fifty men. It is a long story because it deals with a long and brutal battle, the worst of any war. It has two ships because one was sunk, and had to be replaced. It has a hundred and fifty men because that is a manageable number of people to tell a story about. Above all, it is a true story because that is the only kind worth telling.

First, the ocean, the steep Atlantic stream. The map will tell you what that looks like: three-cornered, three thousand miles across and a thousand fathoms deep, bounded by the European coastline and half of Africa, and the vast American continent on the other side: open at the top, like a champagne glass, and at the bottom, like a municipal rubbish dumper. What the map will not tell you is the strength and fury of that ocean, its moods, its violence, its gentle balm, its treachery: what men can do with it, and what it can do with men. But this story will tell you all that.

Then the ship, the first of the two, the doomed one. At the moment she seems far from doomed: she is new, untried, lying in a river that lacks the tang of salt water, waiting for the men to man her. She is a corvette, a new type of escort ship, an experiment designed to meet a desperate situation still over the horizon. She is brand new; the time is November 1939; her name is HMS

Compass Rose.

Lastly, the men, the hundred and fifty men. They come on the stage in twos and threes: some are early, some are late, some, like this pretty ship, are doomed. When they are all assembled, they are a company of sailors. They have women, at least a hundred and fifty women, loving them, or tied to them, or glad to see the last of them as they go to war.

But the men are the stars of this story. The only heroines are the ships: and the only villain the cruel sea itself.

1939: Learning

Lieutenant-Commander George Eastwood Ericson, R.N.R., sat in a stone-cold, draughty, corrugated-iron hut beside the fitting-out dock of Fleming’s Shipyard on the River Clyde. Ericson was a big man, broad and tough, a man to depend on, a man to remember: about forty-two or -three, fair hair going grey, blue eyes as level as a foot rule with wrinkles at the corners – the product of humour and of twenty years’ staring at a thousand horizons. At the moment the wrinkles were complicated by a frown. It was not a worried frown – if Ericson was susceptible to worry he did not show it to the world; it was simply a frown of concentration, a tribute to a problem.

On the desk in front of him was a grubby, thumbed-over file labelled ‘Job No. 2891: Movable Stores’. Through the window and across the dock, right under his competent eye, was a ship: an untidy grey ship, mottled with red lead, noisy with riveting, dirty with an accumulation of wood shavings, cotton waste, and empty paint drums.

The file and the ship were connected, bound together by the frown on his face. For the ship was his: he was to commission and to command HMS

Compass Rose,

and at this moment he did not wholly like the idea.

It was a dislike, a doubt, compounded of a lot of things which ordinarily he would have taken in his stride, if indeed he had noticed them at all. Certainly it had nothing to do with the ship’s name: one could not spend twenty years at sea, first in the Royal Navy and then in the Merchant Service, without coming across some of the most singular names in the world. (The clumsiest he remembered had been a French tramp called the

Marie-Josephe-Brinomar de la Tour-du-Pin

; and the oddest, an East-Coast collier called

Jolly Nights.

)

Compass Rose

was nothing out of the ordinary; it had to be a flower name because she was one of the new Flower Class corvettes, and (Ericson smiled to himself) by the time they got down to

Pansy

and

Stinkwort

and

Love-in-the-Mist,

no one would think anything of

Compass Rose.