The Cosmic Serpent (17 page)

Read The Cosmic Serpent Online

Authors: Jeremy Narby

When we walk in a field, DNA and the cell-based life it codes for are everywhere: inside our own bodies, but also in the puddles, the mud, the cow pies, the grass on which we walk, the air we breathe, the birds, the trees, and everything that lives.

This global network of DNA-based life, this biosphere, encircles the entire earth

.

.

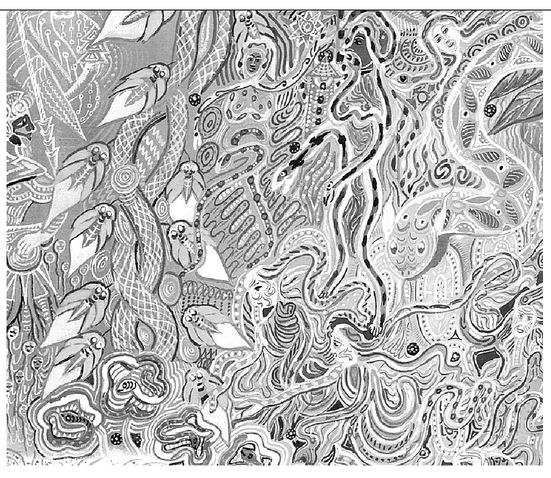

“Cosmovision.” From Gebhart-Sayer (1987, p. 26).

What better image for the DNA-based biosphere than RonÃn, the cosmic anaconda of the Shipibo-Conibo? The anaconda is an amphibious snake, capable of living both in water and on land, just like the biosphere's creatures. Ayahuasquero Laureano Ancon explains the above image: “The earth upon which we find ourselves is a disk floating in great waters. The serpent of the world RonÃn is half-submerged and surrounds it entirely.”

11

11

Here is, according to my conclusions, the great instigator of the hallucinatory images perceived by ayahuasqueros: the crystalline and biospheric network of DNA-based life, alias the cosmic serpent.

Â

DURING MY FIRST AYAHUASCA EXPERIENCE I saw a pair of enormous and terrifying snakes. They conveyed an idea that bowled me over and later encouraged me to reconsider my self-image. They taught me that I was just a human being. To others, this may not seem like a great revelation; but at the time, it was exactly what the young anthropologist I was needed to learn. Above all, it was a thought that I could not have had by myself, precisely because of my anthropocentric presuppositions.

I also felt very clearly that the speed and the coherence of certain sequences of images could not have come from the chaotic storage room of my memory. For example, I saw in a dizzying visual parade the superimposing of the veins of a human hand on those of a green leaf. The message was crystal clear: We are made of the same fabric as the vegetal world. I had never really thought of this so concretely. The day after the ayahuasca session, I felt like a new being, united with nature, proud to be human and to belong to the grandiose web of life surrounding the planet. Once again, this was a totally new and constructive perspective for the materialistic humanist that I was.

This experience troubled me deeply. If I was not the source of these highly coherent and educational images, where did they come from? And who were those snakes who seemed to know me better than myself? When I asked Carlos Perez Shuma, his answer was elliptic: All I had to do was take the snakes' picture the next time I saw them. He did not deny their existenceâon the contrary, he implied that they were as real as the reality we are all familiar with, if not more so.

Detail from Pablo Amaringo's painting “Pregnant by an Anaconda,” reproduced in Luna and Amaringo (1991, p. 111).

Eight years after my first ayahuasca experience, my desire to understand the mystery of the hallucinatory serpents was undiminished. I launched into this investigation and familiarized myself with the different studies of ayahuasca shamanism only to discover that my experience had been commonplace. People who drink ayahuasca see colorful and gigantic snakes more than any other vision

12

âbe it a Tukano Indian, an urbanized shaman, an anthropologist, or a wandering American poet.

13

For instance, serpents are omnipresent in the visionary paintings of Pablo Amaringo

14

(

see above).

12

âbe it a Tukano Indian, an urbanized shaman, an anthropologist, or a wandering American poet.

13

For instance, serpents are omnipresent in the visionary paintings of Pablo Amaringo

14

(

see above).

Over the course of my readings, I discovered that the serpent was associated just about everywhere with shamanic knowledgeâeven in regions where hallucinogens are not used and where snakes are unknown in the local environment. Mircea Eliade says that in Siberia the serpent occurs in shamanic ideology and in the shaman's costume among peoples where “the reptile itself is unknown.”

15

15

Then I learned that in an endless number of myths, a gigantic and terrifying serpent, or a dragon, guards the axis of knowledge, which is represented in the form of a ladder (or a vine, a cord, a tree ...). I also learned that (cosmic) serpents abound in the creation myths of the world and that they are not only at the origin of knowledge, but of life itself.

Snakes are omnipresent not only in the hallucinations, myths, and symbols of human beings in general, but also in their dreams. According to some studies, “Manhattanites dream of them with the same frequency as Zulus.” One of the best-known dreams of this sort is August Kekulé's, the German chemist who discovered the cyclical structure of benzene one night in 1862, when he fell asleep in front of the fire and dreamed of a snake dancing in front of his eyes while biting its tail and taunting him. According to one commentator, “There is hardly any need to recall that this contribution was fundamental for the development of organic chemistry.”

16

16

Why do life-creating, knowledge-imparting snakes appear in the visions, myths, and dreams of human beings around the world?

The question has been asked, and a simple and neurological answer has been proposed and generally accepted: because of the instinctive fear of venom programmed into the brains of primates such as ourselves. Balaji Mundkur, author of the only global study on the matter, writes, “The fundamental cause of the origin of serpent cults seems to be unlike any which gave rise to practically all other animal cults; that fascination by, and awe of, the serpent appears to have been compelled not only by elementary fear of its venom, but also by less palpable, though quite primordial psychological sensitivities rooted in the evolution of the primates; that unlike almost all other animals, serpents, in varying degree, provoke certain characteristically intuitive, irrational, phobic responses in human and nonhuman primates alike; ... and that the serpent's power to fascinate certain primates is dependent on the reaction of the latter's autonomic nervous system to the mere sight of reptilian sinuous movementâa type of response that may have been reinforced by memories of venomous attacks during anthropogenesis and the differentiation of human societies.... The fascination of serpents, in short, is synonymous with a state of fear that amounts, at least temporarily, to

morbid revulsion

or phobia ... whose symptoms few other species of animalsâperhaps noneâcan elicit” (original italics).

17

morbid revulsion

or phobia ... whose symptoms few other species of animalsâperhaps noneâcan elicit” (original italics).

17

In my opinion, this is a typical example of a reductionist, illogical, and inexact answer. Do people really venerate what they fear most? Do people suffering from phobia of spiders, for instance, decorate their clothes with images of spiders, saying, “We venerate these animals because we find them repulsive”? Hardly. Therefore, I doubt that Siberian shamans embellish their costumes with a great number of

ribbons representing serpents

simply because they suffer from a phobia of these reptiles. Besides, most of the serpents found in the costumes of Siberian shamans do not represent real animals, but snakes with two tails. In a great number of creation myths, the serpent that plays the main part is not a real reptile; it is a cosmic serpent and often has two heads, two feet, or two wings or is so big that it wraps around the earth. Furthermore,

venerated serpents are often nonvenomous

. In the Amazon, the nonvenomous snakes such as anacondas and boas are the ones that people consider sacred, like the cosmic anaconda RonÃn. There is no lack of aggressive and deadly snakes with devastating venom in the Amazon, such as the bushmaster and the fer-de-lance, which are an everyday threat to lifeâand yet, they are never worshipped.

18

ribbons representing serpents

simply because they suffer from a phobia of these reptiles. Besides, most of the serpents found in the costumes of Siberian shamans do not represent real animals, but snakes with two tails. In a great number of creation myths, the serpent that plays the main part is not a real reptile; it is a cosmic serpent and often has two heads, two feet, or two wings or is so big that it wraps around the earth. Furthermore,

venerated serpents are often nonvenomous

. In the Amazon, the nonvenomous snakes such as anacondas and boas are the ones that people consider sacred, like the cosmic anaconda RonÃn. There is no lack of aggressive and deadly snakes with devastating venom in the Amazon, such as the bushmaster and the fer-de-lance, which are an everyday threat to lifeâand yet, they are never worshipped.

18

The answer, for me, lies elsewhereâwhich does not mean that primates do not suffer from an instinctive, or even a “programmed,” fear of snakes. My answer is speculative, but could not be more restricted than the generally accepted theory of venom phobia. It is that the global network of DNA-based life emits ultra-weak radio waves, which are currently at the limits of measurement, but which we can nonetheless perceive in states of defocalization, such as hallucinations and dreams. As the aperiodic crystal of DNA is shaped like two entwined serpents, two ribbons, a twisted ladder, a cord, or a vine, we see in our trances serpents, ladders, cords, vines, trees, spirals, crystals, and so on. Because DNA is a master of transformation, we also see jaguars, caymans, bulls, or any other living being. But the favorite newscasters on DNA-TV seem unquestionably to be enormous, fluorescent serpents.

This leads me to suspect that the cosmic serpent is narcissisticâor, at least, obsessed with its own reproduction, even in imagery.

Chapter 9

RECEPTORS AND TRANSMITTERS

My investigation had led me to formulate the following working hypothesis: In their visions, shamans take their consciousness down to the molecular level and gain access to information related to DNA, which they call “animate essences” or “spirits.” This is where they see double helixes, twisted ladders, and chromosome shapes. This is how shamanic cultures have known for millennia that the vital principle is the same for all living beings and is shaped like two entwined serpents (or a vine, a rope, a ladder ...). DNA is the source of their astonishing botanical and medicinal knowledge, which can be attained only in defocalized and “nonrational” states of consciousness, though its results are empirically verifiable. The myths of these cultures are filled with biological imagery. And the shamans' metaphoric explanations correspond quite precisely to the descriptions that biologists are starting to provide.

I knew this hypothesis would be more solid if it rested on a neurological basis, which was not yet the case. I decided to direct my investigation by taking ayahuasqueros at their wordâand they unanimously claimed that certain psychoactive substances (containing molecules that are active in the human brain) influence the spirits in precise ways. The Ashaninca say that by ingesting ayahuasca or tobacco, it is possible to see the normally invisible and hidden maninkari spirits. Carlos Perez Shuma had told me that tobacco attracted the maninkari. Amazonian shamans in general consider tobacco a food for the spirits, who crave it “since they no longer possess fire as human beings do.”

1

If my hypothesis were correct, it ought to be possible to find correspondences between these shamanic notions and the facts established by the study of the neurological activity of these same substances. More precisely, there ought to be an analogous connection between nicotine and DNA contained in the nerve cells of a human brain.

1

If my hypothesis were correct, it ought to be possible to find correspondences between these shamanic notions and the facts established by the study of the neurological activity of these same substances. More precisely, there ought to be an analogous connection between nicotine and DNA contained in the nerve cells of a human brain.

The idea that the maninkari liked tobacco had always seemed funny to me. I considered “spirits” to be imaginary characters who could not really enjoy material substances. I also considered smoking to be a bad habit, and it seemed improbable that spirits (inasmuch as they existed) would suffer from the same kinds of addictive behaviors as human beings. Nevertheless, I had resolved to stop letting myself be held up by such doubts and to pay attention to the literal meaning of the shamans' words, and the shamans were categorical in saying that spirits had an almost insatiable hunger for tobacco.

2

2

Other books

The Time Hunters and the Box of Eternity by Carl Ashmore

Corridors of the Night by Anne Perry

Gordon Ramsay's Ultimate Cookery Course by Ramsay, Gordon

The Survivors: Book One by Angela White, Kim Fillmore, Lanae Morris

La Bocca (the mouth) (The Spitfire) by Silver, Jordan

A Dash of Murder by Teresa Trent

Queen of Diamonds by Barbara Metzger

If You Don't Have Big Breasts, Put Ribbons on Your Pigtails by Barbara Corcoran, Bruce Littlefield

The Hundred Years War by Desmond Seward

Untrue Colors (Entangled Select Suspense) by Veronica Forand