The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five (6 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

5

.

Born in Tibet

(1976), p. 233.

6

.

The Rain of Wisdom

(1980), afterword by the NTC, p. 304.

7

. The translation committee has quite a large number of other members, and it is not feasible to name all of them here. However, in the acknowledgments to

The Rain of Wisdom,

a central translation committee for this project is identified, “consisting of Robin Kornman, John Rockwell, Jr., and Scott Wellenbach in collaboration with Lama Ugyen Shenpen, Loppön Lodrö Dorje Holm, and Larry Mermelstein [the Executive Director of the NTC].” In

The Life of Marpa,

the core group is identified as David Cox, Dana Dudley, John Rockwell, Jr., Ives Waldo, and Gerry Weiner, in collaboration with Loppön Lodrö Dorje and Larry Mermelstein—with much guidance from Trungpa Rinpoche and Lama Ugyen. These are just some of the members of the NTC who worked on these translations. The large membership of the translation group points out how quickly and to what extent Rinpoche was able to share the wealth of his tradition, including so many bright minds and dedicated students in his work.

8

. Traditionally, when a terma text is written out, a special mark or sign is placed at the end of each line of text. The terma marks have been omitted from the excerpt from

The Sadhana of Mahamudra

that appears in Volume Five.

9

. See the introduction to Volume One for Richard Arthure’s comments on the editing of

Meditation in Action.

10

. It was during the 1968 visit to Asia that Rinpoche met Thomas Merton, shortly before Merton’s untimely death.

11

. Karma Pakshi (1203–1282) was the second Karmapa. He was invited to China by Prince Kublai Khan and by his rival and older brother, Mongka Khan. When His Holiness the sixteenth Karmapa made his second visit to the United States in 1976, Trungpa Rinpoche asked him to perform the Karma Pakshi abhisheka as a blessing for all of Rinpoche’s students, which he did.

12

.

Delek

is a Tibetan word that means “auspicious happiness.” Chögyam Trungpa used it to refer to creating a system of governance that fosters peace and good communication within the meditation centers he established. The discussion here is of the genesis of the idea of the delek system in 1968. Trungpa Rinpoche did not actually introduce deleks until 1981. At that time, he suggested that people in the Buddhist communities he worked with should organize themselves into deleks, or groups, consisting of about twenty or thirty families, based on the neighborhoods in which they lived. Each neighborhood or small group was a delek and its members, the delekpas. Each delek would elect a leader, the dekyong—the “protector of happiness”—by a process of consensus for which Rinpoche coined the phrase “spontaneous insight.” The dekyongs were then organized into the Dekyong Council, which would meet and make decisions affecting their deleks and make recommendations to the administration of Vajradhatu, the international organization he founded, about larger issues.

13

. This line is not part of the excerpt printed in Volume Five.

14

. Letter from Richard Arthure to Carolyn Rose Gimian, December 2001.

15

. The Nālandā Translation Committee did prepare a more literal translation of

The Sadhana of Mahamudra

in 1990, for students’ use in studying the text. The beginning sections of this translation were done with Chögyam Trungpa. He himself felt that the original translation captured something that would be lost by making extensive changes. The NTC’s work is available to interested students.

C

RAZY

W

ISDOM

EDITED BY

S

HERAB

C

HÖDZIN

K

OHN

Editor’s Foreword

T

HE

V

ENERABLE

C

HÖGYAM

T

RUNGPA

R

INPOCHE

gave two seminars on “crazy wisdom” in December 1972. Each lasted about a week. The first took place in an otherwise unoccupied resort hotel in the Tetons near Jackson Hole, Wyoming. The other happened in an old town hall cum gymnasium in the Vermont village of Barnet, just down the road from the meditation center founded by Trungpa Rinpoche now called Karmê Chöling, then known as Tail of the Tiger.

Rinpoche had arrived on this continent about two and a half years previously, in the spring of 1970. He had found an America bubbling with social change, animated by factors like hippyism, LSD, and the spiritual supermarket. In response to his ceaseless outpouring of teachings in a very direct, lucid, and down-to-earth style, a body of committed students had gathered, and more were arriving all the time. In the fall of 1972, he made his first tactical pause, taking a three-month retreat in a secluded house in the Massachusetts woods.

This was a visionary three months. Rinpoche seemed to contemplate the direction his work in America would take and the means at hand for its fulfillment. Important new plans were formulated. The last night of the retreat, he did not sleep. He told the few students present to use whatever was on hand and prepare a formal banquet. He himself spent hours in preparation for the banquet and did not appear until two in the morning—very beautifully groomed and dressed and buzzing with extraordinary energy. Conversation went on into the night. At one point, Rinpoche talked for two hours without stopping, giving an extremely vivid and detailed account of a dream he had had the night before. He left the retreat with the dawn light and traveled all that day. That evening, still not having slept, he gave the first talk of the “Crazy Wisdom” seminar at Jackson Hole. It is possible that he went off that morning with a sense of beginning a new phase in his work. Certainly elements of such a new phase are described in the last talk of the seminar at Jackson Hole.

After the first Vajradhatu Seminary in 1973 (planned during the 1972 retreat), Trungpa Rinpoche’s teaching style would change. His presentation would become much more methodical, geared toward guiding his students through the successive stages of the path. The “Crazy Wisdom” seminars thus belonged to the end of the introductory period of Rinpoche’s teaching in North America, during which, by contrast, he showed a spectacular ability to convey all levels of the teachings at once. During this introductory phase, there was a powerful fruitional atmosphere, bursting with the possibilities of the sudden path. Such an atmosphere prevailed as he made the basic teachings and advanced teachings into a single flow of profound instruction, while at the same time fiercely lopping away the omnipresent tentacles of spiritual materialism.

It might be helpful to look at these two seminars for a moment in the context of the battle against spiritual materialism. Though they had been planned in response to a request for teaching on the eight aspects of Padmasambhava, Trungpa Rinpoche had slightly shifted the emphasis and given the headline to crazy wisdom. His “experienced” students, as well as the ones newly arriving, had a relentless appetite for definite spiritual techniques or principles they could latch onto and identify with. The exotic iconography of the eight aspects of Padmasambhava, if presented too definitely, would have been bloody meat in the water for spiritually materialistic sharks. This may partly explain why a tidy hagiography of the eight aspects, with complete and consistent detail, was avoided, and the raw, ungarnished insight of crazy wisdom was delivered instead.

Some editing of this material from the original spoken presentation has been necessary for the sake of basic readability. However, nothing has been changed in the order of presentation, and nothing has been left out in the body of the talks. A great effort has been made not to cosmeticize Trungpa Rinpoche’s language or alter his diction purely for the sake of achieving a conventionally presentable tone. Hopefully, the reader will enjoy those sentences of his that run between our mental raindrops and touch us where ordinary conceptual clarity could not. The reader will also hopefully appreciate that passages that remain dark on one reading may become luminously clear on another.

Here, we have the mighty roaring of a great lion of dharma. May it put to flight the heretics and bandits of hope and fear. For the benefit of all beings, may his wishes continue to be fulfilled.

CRAZY WISDOM SEMINAR I

Jackson Hole, 1972

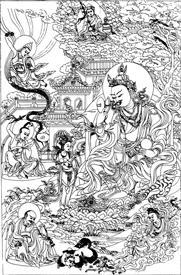

Pema Gyalpo (Padmasambhava)

.

ONE

Padmasambhava and Spiritual Materialism

T

HE SUBJECT

that we are going to deal with is an extraordinarily difficult one. It is possible that some people might get extraordinarily confused. Or people might very well get something out of it. We will be discussing Guru Rinpoche, or as he is often called in the West, Padmasambhava; we will be considering his nature and the various lifestyles he developed in the process of working with students. This subject is very subtle, and some aspects of it are very difficult to put into words. I hope nobody will regard this humble attempt of mine as a definitive portrayal of Padmasambhava.

To begin with, we probably need some basic introduction to who Padmasambhava was; to how he fits into the context of the buddhadharma (the Buddhist teachings), in general; and to how he came to be so admired by Tibetans in particular.

Padmasambhava was an Indian teacher who brought the complete teachings of the buddhadharma to Tibet. He remains our source of inspiration even now, here in the West. We have inherited his teachings, and from that point of view, I think we could say that Padmasambhava is alive and well.

I suppose the best way to characterize Padmasambhava for people with a Western or Christian cultural outlook is to say that he was a saint. We are going to discuss the depth of his wisdom and his lifestyle, his skillful way of relating with students. The students he had to deal with were Tibetans, who were extraordinarily savage and uncultured. He was invited to come to Tibet, but the Tibetans showed very little understanding of how to receive and welcome a great guru from another part of the world. They were very stubborn and very matter-of-fact—very earthy. They presented all kinds of obstacles to Padmasambhava’s activity in Tibet. However, the obstacles did not come from the Tibetan people alone, but also from differences in climate, landscape, and the social situation as a whole. In some ways, Padmasambhava’s situation was very similar to our situation here. Americans are hospitable, but on the other hand, there is a very savage and rugged side to American culture. Spiritually, American culture is not conducive to just bringing out the brilliant light and expecting it to be accepted.

So there is an analogy here. In terms of that analogy, the Tibetans are the Americans and Padmasambhava is himself.

Before getting into details concerning Padmasambhava’s life and teachings, I think it would be helpful to discuss the idea of a saint in the Buddhist tradition. The idea of a saint in the Christian tradition and the idea of a saint in the Buddhist tradition are somewhat conflicting. In the Christian tradition, a saint is generally considered someone who has direct communication with God, who perhaps is completely intoxicated with the Godhead and because of this is able to give out certain reassurances to people. People can look to the saint as an example of higher consciousness or higher development.

The Buddhist approach to spirituality is quite different. It is nontheistic. It does not have the principle of an external divinity. Thus, there is no possibility of getting promises from the divinity and bringing them from there down to here. The Buddhist approach to spirituality is connected with awakening within oneself rather than with relating to something external. So the idea of a saint as someone who is able to expand himself to relate to an external principle, get something out of it, and then share that with others is difficult or nonexistent from the Buddhist point of view.

A saint in the Buddhist context—for example, Padmasambhava or a great being like the Buddha himself—is someone who provides an example of the fact that completely ordinary, confused human beings can wake themselves up; they can put themselves together and wake themselves up through an accident of life of one kind or another. The pain, the suffering of all kinds, the misery, and the chaos that are part of life begins to wake them, shake them. Having been shaken, they begin to question: “Who am I? What am I? How is it that all these things are happening?” Then they go further and realize that there is something in them that is asking these questions, something that is, in fact, intelligent and not exactly confused.

This happens in our own lives. We feel a sense of confusion—it seems to be confusion—but that confusion brings out something that is worth exploring. The questions that we ask in the midst of our confusion are potent questions, questions that we really have. We ask, “Who am I? What am I? What is this? What is life?” and so forth. Then we explore further and ask, “In fact, who on earth asked that question? Who is that person who asked the question, ‘Who am I?’ Who is the person who asked, ‘What is?’ or even ‘What is what is?’” We go on and on with this questioning, further and further inward. In some way, this is nontheistic spirituality in its fullest sense. External inspirations do not stimulate us to model ourselves on further external situations. Rather the external situations that exist speak to us of our confusion, and this makes us think more, think further. Once we have begun to do that, then of course there is the other problem: once we have found out who and what we are, how do we apply what we have learned to our living situation? How do we put it into practice?