The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five (10 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Five Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

S:

How does this relate to confusion?

TR:

Confusion is the other partner. If there is understanding, that understanding usually has its own built-in limitation of understanding. Thus, confusion is there automatically until the absolute level is reached, where understanding does not need its own help, because the entire situation is an understood situation.

Student:

How does this apply to daily life?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Well, in daily life, it’s just the same. Working with the totality, there is basic room to work with life, and also there is energy and practicality involved. In other words, we are not limited to a particular thing. A lot of the frustration we have with our lives comes from the feeling that there are inadequate means to change and improvise with our life situations. But those three principles of dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, and nirmanakaya provide us with tremendous possibilities for improvisation. There are endless resources of all kinds we could work with.

Student:

What was Padmasambhava’s relationship with King Indrabhuti all about? How did it relate to his development from his basic innocence?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

King Indrabhuti was the first audience, the first representative of samsara. Indrabhuti’s bringing him to the palace was the starting point for learning how to work with students, confused people. Indrabhuti provided a strong father-figure representation of confused mind.

Student:

Who were the mother and son who were killed?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

There have been several interpretations of that in the scriptures and commentaries concerning Padmasambhava’s life. Since the vajra is connected with skillful means, the child killed by the vajra is the opposite of skillful means, which is aggression. The trident is connected with wisdom, so the mother killed by it represents ignorance. And there area also further justifications based on the karma of previous lives: the son was so-and-so and committed thus-and-such a bad karmic act, and the same with the mother. But I don’t think we have to go into those details. It gets a bit too complicated. The story of Padmasambhava at this point is in a completely different dimension—that of the psychological world. It comes down to a practical level, so to speak, when he gets to Tibet and begins dealing with the Tibetans. Before that, it is very much in the realm of mind.

Student:

Is there any analogy between these two deaths and the sword of Manjushri cutting the root of ignorance? Or the Buddha’s speaking about shunyata, emptiness, and some of his disciples having heart attacks?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

I don’t think so. The sword of Manjushri is very much oriented toward practice on the path, but the story of Padmasambhava is related with the goal. Once you have already experienced the sudden flash of enlightenment, how do you handle yourself beyond that? The Manjushri story and the story of the

Heart Sutra

and all the other stories of sutra teaching correspond to the hinayana and mahayana levels and are designed for the seeker on the path. What we are discussing here is the umbrella notion—the notion of coming down from the top: having already attained enlightenment, how do we work with further programs? The story of Padmasambhava is a manual for buddhas—and each of us is one of them.

Student:

Was he experimenting with motive?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Well, in the realm of the dharmakaya, it is very difficult to say what is and what is not the motive. There isn’t anything at all.

Student:

I would like to know more about the contrasting metaphors of eating out from the inside and stripping away layers from the outside. If I understood correctly, stripping away is the bodhisattva path, whereas on the tantric path, you’re eating out from the inside. But I really don’t understand the metaphors.

Trungpa Rinpoche:

The whole point is that tantra is contagious. It involves a very powerful substance, which is buddha nature eating out from the inside rather than being reached by stripping away layers from the outside. In Padmasambhava’s life story, we are discussing the goal as the path, rather than the path as the path. It is a different perspective altogether; it is not the point of view of sentient beings trying to attain enlightenment, but the point of view of an enlightened person trying to relate with sentient beings. That is why the tantric approach is that of eating outward, from the inside to the outside. Padmasambhava’s difficulties with his father, King Indrabhuti, and with the murder of the child and his mother are all connected with sentient beings. We are telling the story from the inside rather than looking at somebody else’s newsreel taken from the outside.

Student:

How does the eating away outward take place?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Through dealing with situations skillfully. The situations are already created for you, and you just go out and launch yourself along with them. It is a self-existing jigsaw puzzle that has been put together by itself.

Student:

Is it the dharmakaya aspect that diffuses hope and fear?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Yes, that seems to be the basic thing. Hope and fear are all-pervading, like a haunted situation. But the dharmakaya takes away the haunt altogether.

Student:

Are you saying that the story of Padmasambhava, from his birth in the lotus through his destroying all the layers of students’ expectations and finally manifesting as Dorje Trolö, is moving from the dharmakaya slowly into the nirmanakaya?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Yes, that is what I have been trying to get at. So far, he has risen out of the dharmakaya and has just gotten to the fringe of the sambhogakaya. Sambhogakaya is the energy principle, or the dance principle—dharmakaya being the total background.

S:

Is it that hope and fear have to fade away before the—

TR:

Before the dance can take place. Yes, definitely.

Student:

Is the sambhogakaya energy the energy that desire and anger are attached to?

Trungpa Rinpoche:

The sambhogakaya level doesn’t seem to be that. It is the positive aspect that is left by the unmasking process. In other words, you get the absence of aggression and that absence is turned into energy.

S:

So when the defilements are transformed into wisdom—

TR:

Transmuted. It is even more than transmutation—I don’t know what sort of a word there is. The defilements are being so completely related to that their function becomes useless, but their nonfunctioning becomes useful. There is another kind of energy in sambhogakaya.

Student:

There seems to be some kind of cosmic joke about the whole thing. What you’re saying is that you have to take the first step, but you can’t take the first step until you take the first step.

Trungpa Rinpoche:

Yes, you have to be pushed into it. That is where the relationship between teacher and student comes in. Somebody has to push. That is the very primitive level at the beginning.

S:

Are you pushing?

TR:

I think so.

FOUR

Eternity and the Charnel Ground

I

WOULD LIKE TO MAKE SURE

that what we have already discussed is quite clear. The birth of Padmasambhava is like a sudden experience of the awakened state. The birth of Padmasambhava cannot take place unless there is an experience of the awakened state of mind that shows us our innocence, our infantlike quality. And Padmasambhava’s experiences with King Indrabhuti of Uddiyana are connected with going further after one has already had a sudden glimpse of awake. That seems to be the teaching, or message, of Padmasambhava’s life so far.

Now let us go on to the next aspect of Padmasambhava. Having experienced the awakened state of mind, and having had experiences of sexuality and aggression and all the pleasures that exist in the world, there is still uncertainty about how to work with those worldly processes. Padmasambhava is uncertain not in the sense of being confused, but about how to teach, how to connect with the audience. The students themselves are apprehensive, because for one thing, they have never dealt with an enlightened person before. Working with an enlightened person is extraordinarily sensitive and pleasurable, but at the same time, it could be quite destructive. If we did the wrong thing, we might be hit or destroyed. It is like playing with fire.

So Padmasambhava’s experience of relating with samsaric mind continues. He is expelled from the palace, and he goes on making further discoveries. The discovery that he makes at this point is eternity. Eternity here is the sense that the experience of awake is constantly going on without any fluctuations—and without any decisions to be made, for that matter. At this point, in connection with the second aspect, the decisionlessness of Padmasambhava’s experience of dealing with sentient beings becomes prominent.

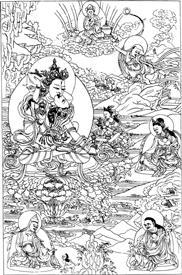

Vajradhara.

Padmasambhava’s second aspect is called Vajradhara. Vajradhara is a principle or a state of mind that possesses fearlessness. The fear of death, the fear of pain and misery—all such fears—have been transcended. Having transcended those states, the eternity of life goes on beyond them. Such eternity is not particularly dependent on life situations and whether or not we make them healthier or whether or not we achieve longevity. It is not dependent on anything of that nature.

We are discussing a sense of eternity that could apply to our own lives as well. This attitude of eternity is quite different from the conventional spiritual idea of eternity. The conventional idea is that if you attain a certain level of spiritual one-upmanship, you will be free from birth and death. You will exist forever and be able to watch the play of the world and have power over everything. It is the notion of the superman who cannot be destroyed, the good savior who helps everybody using his Superman outfit. This general notion of eternity and spirituality is somewhat distorted, somewhat cartoonlike: the spiritual superman has power over others, and therefore he can attain longevity, which is a continuity of his power over others. Of course, he does also help others at the same time.

As Vajradhara, Padmasambhava’s experience of eternity—or his existence as eternity—is quite different. There is a sense of continuity, because he has transcended the fear of birth, death, illness, and any kind of pain. There is a constant living, electric experience that he is not really living and existing, but rather it is the world that lives and exists, and therefore he is the world and the world is him. He has power over the world because he does not have power over the world. He does not want to hold any kind of position as a powerful person at this point.

Vajradhara is a Sanskrit name.

Vajra

means “indestructible,”

dhara

means “holder.” So it is as the “holder of indestructibility” or “holder of immovability” that Padmasambhava attains the state of eternity. He attains it because he was born as an absolutely pure and completely innocent child—so pure and innocent that he had no fear of exploring the world of birth and death, of passion and aggression. That was the preparation for his existence, but his exploration continued beyond that level. Birth and death and other kinds of threats might be seen by samsaric or confused mind as solid parts of a solid world. But instead of seeing the world as a threatening situation, he began to see it as his home. In this way, he attained the primordial state of eternity, which is quite different from the state of perpetuating ego. Ego needs to maintain itself constantly; it constantly needs further reassurance. But in this case, through transcending spiritual materialism, Padmasambhava attained an ongoing, constant state based on being inspired by fellow confused people, sentient beings.

The young prince, recently turned out of his palace, roamed around the charnel ground. There were floating skeletons with floating hair. Jackals and vultures, hovering about, made their noises. The smell of rotten bodies was all over the place. The genteel young prince seemed to fit in to that scene quite well, as incongruous as it might seem. He was quite fearless, and his fearlessness became accommodation as he roamed through the jungle charnel ground of Silwa Tsal near Bodhgaya. There were awesome-looking trees and terrifying rock shapes and the ruins of a temple. The whole feeling was one of death and desolation. He’d been abandoned, he’d been kicked out of his kingdom, but still he roamed and played about as if nothing had happened. In fact, he regarded this place as another palace in spite of all its terrifying sights. Seeing the impermanence of life, he discovered the eternity of life, the constant changing process of death and birth taking place all the time.

There was a famine in the vicinity. People were continually dying. Sometimes half-dead bodies were brought to the charnel ground, because people were so exhausted with the constant play of death and sickness. There were flies, worms, maggots, and snakes. Padmasambhava, this young prince who had recently been turned out of a jewel-laden palace, made a home out of this; seeing no difference at all between this charnel ground and a palace, he took delight in it.