The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight (50 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

In order to help somebody, first raise your head and shoulders. Then, don’t try to convert people to your dogma, but just encourage them. Whatever profession they have—whether they are dairy farmers, lawyers, or cab drivers—first, raise

your

consciousness, and then talk to them on their own terms. Don’t try to make them join the Shambhala club or the Buddhist scene or anything like that. Just let them

be

in their own way. Have a drink, have dinner, make a date with them—just keep it simple.

The main point is definitely not to get them to join your organization. That is the

least

of the points. The main point is to help others be good human beings

in their own way

. We are not into converting people. They may convert themselves, but we just keep in touch with them. Usually, in any organization, people cannot keep themselves from drawing others into their scene or their trip, so to speak. That is not our plan. Our plan is to make sure that individuals, whoever we meet, have a good life. At the same time, you should keep in contact with people, in whatever way you can. That’s very important, not because we’re into converting others, but because we are into communicating.

When you are trying to help others, you will probably feel lonely, feeling that you don’t have a partner to work with. You may also begin to feel that the world is so disordered. I personally feel sadness, always. You feel sad, but you don’t really want to burst into tears. You feel embryonic sadness. There are hundreds of thousands of people who need your help, which makes you feel sad, so sad. It’s not that you need someone to keep you company, but it is sad because you feel the sense of aloneness, and others do not. Many people have this experience. For example, I have a friend and student named Baird Bryant whom I’ve worked with for many years. He is a filmmaker, and we worked together on several films. I can see that he has that kind of sadness. He wishes that something could be done for others, that something could be made right. He has that sadness, aloneness, and loneliness, which I appreciate very much. In fact, I have learned from witnessing my best friend’s experience.

There are two types of sadness. The first is when you look at a beautiful flower and you wish you could

be

that flower. It is so beautiful. The second is that nobody else understands that flower. It’s so beautiful, utterly beautiful, so magnificent. Nobody understands that. In spite of that beauty, people are killing each other. They’re destroying each other. They go to the bar and get drunk instead of thinking of that beautiful flower.

That sadness is a key point, ladies and gentlemen. In the back of your head, you hear a beautiful flute playing, because you are so sad. At the same time, the melody cheers you up. You are not on the bottom of the barrel of the world or in the Black Hole of Calcutta. In spite of being sad and devastated, there is something lovely taking place. There is some smile, some beauty. In the Shambhala world, we call that

daringness

. In the Buddhist language, we call it compassion. Daringness is sympathetic to oneself. There is no suicidal sadness involved

at all

. Rather, there is a sense of big, open mind in dealing with others, which is beautiful, wonderful.

We find ourselves shedding tears at the same time that we are smiling. We are crying and laughing at once. That is the ideal Shambhalian mentality: we cry and we smile at the same time. Isn’t it wonderful? A flower needs sunshine together with raindrops to blossom so beautifully. For that matter, a rainbow is made out of the tears falling from our eyes, mixed with a shot of sunshine. That is how a rainbow becomes a rainbow—sunshine mixed with tears. From that point of view, the Shambhala philosophy is the philosophy of a rainbow.

Daringness also means that you are not afraid to let go when you help others. You wouldn’t hesitate to say to someone, “Don’t you think you should be more daring, Mr. Joe Schmidt? I see that you’re at the end of your rope. You’re not doing so good. Don’t you think you should pick up your end of the rope and smile with me?” A Shambhala person can help others in that way—in many ways. A Shambhala person can also

demonstrate

warriorship to others. If I slump down like this, what does this posture say? Can somebody please answer? Please talk into the microphone so that we get this on tape. People of future generations have to hear what you’re saying. We are making history, you see.

Student:

That posture looks sleepy and floppy. It doesn’t communicate much of anything.

Dorje Dradül of Mukpo:

Yes. OK. Now, how about when I sit up like this?

Second student:

There’s a sense of joy that just spills over.

Dorje Dradül of Mukpo:

Well . . . we have to be careful about saying “joy.” We’re not only cultivating joy. This posture is also cultivating strength and the ability to work with others. You don’t just purely feel good, right? Thank you very much. Could someone else say something? The young lady over there?

Third student:

The second, upright, posture is certainly more warrior-like than the slumped-down one. Confidence and strength are qualities that also occur to me.

Dorje Dradül of Mukpo:

How would you explain a Shambhala warrior to somebody who just came out of McDonald’s?

Student:

I would try to communicate to them that the Shambhala warrior does not go out to fight like the warriors I learned about in history class. I would try to communicate that the Shambhala warrior is fearless, ready to meet the world head-on, not necessarily charging into it, but being open to anything that comes in. The Shambhala warrior is fearless and brave.

Dorje Dradül of Mukpo:

Jolly good. That’s wonderful. Thank you, sweetheart. You make me melt. Young warrior, your goodness makes me melt. Thank you very much.

In communicating with others, we can definitely make a profound statement. We can communicate with others about their state of being, their own pain, their own pleasure. We don’t feel that this world is bad. We feel that this world has basic goodness. We can communicate that.

We don’t have to run away from this world. We don’t have to feel harsh and

deprived

. We can contribute a lot to the world, and we can

raise

ourselves up in this world. We should feel

so good

. This world is the best world. As we raise up the world, we should also feel good, both at once, right? There are all sorts of ways to do that. If you drive into the mountains with a friend, you may see the mountain deer. They’re so well groomed, although they don’t live on a farm. They have tremendous head and shoulders, and their horns are so beautiful. The birds who land on your porch are also well groomed, because they are not conditioned by ordinary conditionality. They are themselves. They are so good.

Look at the sun. The sun is shining. Nobody polishes the sun. The sun just shines. Look at the moon, the sky, the world at its best. Unfortunately, we human beings try to fit everything into conditionality. We try to make something out of nothing. We have messed everything up. That’s

our

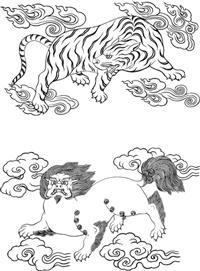

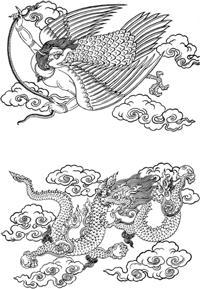

problem. We have to go back to the sun and the moon, to dragons, tigers, lions, garudas.

1

We can be like the blue sky, sweethearts, and the clouds so clean, so beautiful.

We don’t have to try

too

hard to find ourselves. We haven’t really lost anything; we just have to tune in. The majesty of the world is always there, always there, even from the simplest point of view. In order to help others, we aren’t going to conquer anybody and turn them into a serf, although sometimes we might have to conquer their confusion. Human beings need education so badly, in order to raise themselves to a higher level of existence.

So there’s one last thing, which is said very ironically. Am I mad? Or are you mad? As far as I can see, I’m not mad. I appreciate this beautiful world so much, which might mean that I am mad. You could put me in the nuthouse.

Or

we could all go into the nuthouse. I’m only joking!

Tiger, lion, garuda, and dragon

.

LINE DRAWINGS BY SHERAP PALDEN BERU.

In order to help others, stay with the sadness. Stay with the sadness completely. Sadness is your first perception of somebody. Then you might feel anger, as the methodology to help them. You might have to say rather angrily to somebody, “Now, pull yourself together, OK?” We can’t just view the world as if nothing bad had ever happened. That won’t do. We have to get into the world. We have to involve ourselves in the setting sun. When you first see a person, you see that person with Great Eastern Sun possibilities. When you actually work with that person, you have to help him or her overcome the setting sun, making sure that the person is no longer involved with setting-sun possibilities.

To do that, you have to have humor, self-existing humor, and you have to hold the moth in your hand, but not let it go into the flame. That’s what helping others means. Ladies and gentlemen, we have so much responsibility. A long time ago, people helped one another in this way. Now people just talk, talk, and talk. They read books, they listen to music, but they never actually help anyone. They never use their bare hands to save a person from going crazy. We have that responsibility. Somebody has to do it. It turns out to be us. We’ve

got

to do it, and we can do it with a smile, not with a long face.

Student:

Why do you think

we’ve

got to do it?

Dorje Dradül of Mukpo:

Why do

we

have to do it? Somebody has to do it. Suppose you’re very badly hurt in a car crash. Why does anybody have to help you? Somebody’s got to do it. In this case, we have that responsibility, that absolute responsibility. As far as I’m concerned, I’m willing to take responsibility, and I appreciate the opportunity very much. I’ve been a prince, I’ve been a monk, I’ve been a householder: I’ve experienced all kinds of human life. And I appreciate life. I do not resent being born on this earth

at all

. I appreciate it. I love it. That’s why I am called

Lord

Mukpo: because I love this world so much.

The world doesn’t put me off

at all

. Due to my education and my studies with my teacher, I love the world. I love to go to New York City, for instance, because I love the chaos. Sometimes I wonder whether I’m a maniac, because I just want to

save everybody

. Perhaps I am. But then the dralas

2

tell me, “No, you are not a maniac.” The death of His Holiness Karmapa has left me with a lot of responsibility, but I’m quite happy to take it on.

Second student:

I’m very glad to meet you finally. But it’s a little disconcerting to come here out of self-interest and to find out that I’m about to go out and help everybody else.

Dorje Dradül of Mukpo:

You have to help yourself first, so you’ll be ready to help others. Tomorrow there will be a transmission of how to do it, how to actually

be

a warrior. In connection with that, I would like everybody to think about how to help others. Last night, I couldn’t help myself. I had to present the initial realization and understanding of how you can actually

be,

to begin with. Tonight has been more pragmatic, more of the working situation. Tomorrow we can go beyond that.

I’m

so proud

of you, absolutely so proud. You’ve all had many samsaric experiences in the past, but at this point, I’m so proud of you. I would very very much like to thank you. Very much. On the whole, I would really

very VERY

much like to say, ladies and gentlemen, that you are all worthy subjects of the Shambhala Kingdom. We are one. In order to create enlightened society, men and women like you are very necessary. Thank you very much.

Tonight, I would like to introduce the Shambhala warrior’s cry. Chanting this cry is a way to rouse your head and shoulders, a way to rouse a sense of uplifted dignity. It is also a way to invoke the power of windhorse and the energy of basic goodness. We might call it a battle cry, as long as you understand that this particular battle is fighting against aggression, conquering aggression, rather than promoting hatred or warfare. We could say that the warrior’s cry celebrates victory over war, victory over aggression. It is also a celebration of overcoming obstacles. The warrior’s cry goes like this: Ki Ki So So.

Ki

is primordial energy, similar to the idea of ch’i in the Chinese martial arts.

So

is furthering or extending that energy of ki and extending the power of Ki Ki So So altogether. Let us close our meeting by shouting “Ki Ki So So” three times.

3

Sitting in good warrior posture, with your hands on your hips, hold your head and shoulders and shout: