The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight (48 page)

Read The Collected Works of Chögyam Trungpa: Volume Eight Online

Authors: Chögyam Trungpa

Tags: #Tibetan Buddhism

You have to make an effort to achieve these seven virtues of the higher realms. They are a journey: one virtue leads to the next. So attaining the seven virtues is a linear process, but at the same time, each of them is connected with fundamental discipline. Because of

faith,

one is inspired to have

discipline

. Because of discipline, therefore, one becomes

daring

. Because of daringness, you want to learn more. As you acquire knowledge from

learning,

you develop

decorum

. Because of your decorum and elegance, you begin to develop

modesty

and humbleness. You are not bloated. And because of your humbleness, you begin to have

discriminating awareness,

knowing how to distinguish one thing from another, what to accept and what to reject.

By practicing the virtues of the higher realms, you develop the capability to bring about

the

first thought. Sometimes your so-called first thought is filled with aggression, resentment, or some other habitual pattern. At that point, you’re experiencing second thought rather than the real first thought. It’s not fresh. It is like wearing a shirt for the second time. It’s been worn before, so you can’t quite call it a clean shirt. That is like missing the first thought. First thought is fresh thought. By practicing the virtues of the higher realms, you can bring about the fresh first thought. It is possible. Then you begin to see the dot in space much more clearly and precisely. Of course, these seven disciplines are not conducted with a long face, but with the joy of taking a walk in the woods, with a sense of rejuvenating and refreshing oneself.

In Tibet, when children reach the age of seven or eight, we let them use knives. Sometimes they cut themselves, but most of the time they don’t, because they are old enough to learn to use a knife properly. They learn to be cautious, and they learn that they are actually capable. At the age of eight, children in a Tibetan farming village may be put in charge of a herd of animals, including the young lambs and calves. We send the children out in the mountains to take care of their animals. They have to pay heed and bring the sheep and cows back to the village when it is milking time. They have to be sure the little ones are safe, and they are told ways to ward off wild animals. All that knowledge is passed on to the children.

So children in Tibet don’t play all the time. They play, but they work at the same time. In that way, they develop a sense of how to lead life and how to grow up. I think one of the problems in the West is that children have too much access to toys and not enough access to reality. They can’t actually go out and do anything constructive by themselves. They have to imagine that they’re working. It’s healthy to introduce young people to the real world, instead of just saying, “He’s a child. He can’t do that. We are the adults. We have to take care of the children.” The limitations we place on children are quite hypothetical. We have so many preconceptions about young people. Children can take care of young animals, just as they learn to read and write. They do it very well.

In my country, there were very few schools. Children were mostly taught by their parents and grandparents. They didn’t regard learning to read and write as a duty. Children today often say, “Do we

have

to go to school?” But in Tibet, they regarded it as a natural part of their growing process, as much as herding cattle or sheep. There was less preconception and more realism in children’s upbringing. There was much more of a sense of becoming an individual, being less dependent on others. So in that way, learning to be alone in one’s early years can be the beginning of warrior training.

We’ve been here on this earth for millions of years. Confusion has been handed down to us, and we are busy making confusion for others—by trying to make money from others or by coming up with all sorts of gimmicks, all sorts of easy ways to deal with things. In the mechanical age, there is too much reference to comfort. For parents today, sending their children to school is viewed as relief. You park the children in school for part of the day, and then you have time for yourself. A lot of problems come from that kind of laziness. We don’t really want to deal with problems; we don’t want to dirty our hands anymore. Reality has been handed down to you through somebody else’s experiences, and you don’t want to experience reality for yourself. Bad information and laziness have been handed down to us, and we become the product of that mentality.

Then nobody wants to take a walk in the woods, certainly not by themselves. If you do go for a walk, you bring at least three or four people with you and your camping gear. You bring along butane gas, so that you don’t have to collect wood to make a fire in the woods. You cook your food on your butane stove, and you certainly don’t sleep on the ground. You have a comfortable pad in your little tent. Everything is shielded from reality. I’m not particularly suggesting that we become naturalists and forget about modern technology. But one has to be alone. One has to really learn to face aloneness. When you get a little prick from brushing your hand against a branch in the woods, you don’t immediately have to put a Band-Aid on it. You can let yourself bleed a little bit. You may not even need a Band-Aid. The scratch might heal by itself.

Things have become so organized and institutionalized. Technology is excellent. It is the product of centuries and centuries of work. Hundreds of thousands of people worked to achieve the technology we enjoy. It’s great. It’s praiseworthy. But at the same time, the way we use technology is problematic. Ça va?

One needs discipline with enjoyment. In the Shambhala tradition, the sitting practice of meditation is the fundamental discipline. At the beginning, there is resistance to sitting on a meditation cushion and being still. Once you pass that resistance, that barrier, that particular Great Wall of China, then you are inside the Great Wall, and you can appreciate the uprightness, purity, and freshness.

If there is a temptation to stop paying attention, you bring yourself back. It’s like herding a group of cows who would like to cross the fence into the neighbor’s field. You have to push them back, but you do it with a certain sense of enjoyment. Discipline is a very personal experience, extremely personal. It’s like hugging somebody. When you give somebody a hug, you wonder, “Who is going to stop hugging first? Shall I do it? Or will the other person?”

You have such enthusiasm and basic goodness. Although you may not believe it, it is dazzling in you. We can communicate the vision of the Great Eastern Sun to others, for the very fact that we and they both have it within ourselves. Suppose everybody believed that they had only one eye. We would have to let everybody know that they have two eyes. In the beginning, there would be a lot of people against us, saying that it’s not true. They would accuse us of giving out the wrong information, because they’d been told and they believed that they only have one eye. Eventually, however, somebody would realize that they actually had two eyes, and then that knowledge would begin to spread. The Shambhala wisdom is actually as stupid or literal as that. It’s very obvious. But because of our habitual tendencies and other obstacles, we’ve never allowed ourselves to believe in it or look at it at all. Once we begin to do so, we will realize that it’s possible and true.

T

HE

M

EEK

Powerfully Nonchalant and Dangerously Self-Satisfying

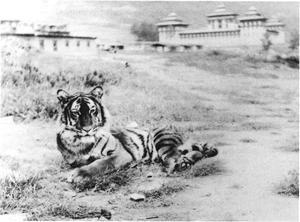

In the midst of thick jungle

Monkeys swing,

Snakes coil,

Days and nights go by.

Suddenly I witness you,

Striped like sun and shade put together.

You slowly scan and sniff, perking your ears,

Listening to the creeping and rustling sounds:

You have supersensitive antennae.

Walking gently, roaming thoroughly,

Pressing paws with claws,

Moving with the sun’s camouflage,

Your well-groomed exquisite coat has never been touched or hampered by others.

Each hair bristles with a life of its own.

In spite of your feline bounciness and creeping slippery accomplishment,

Pretending to be meek,

You drool as you lick your mouth.

You are hungry for prey—

You pounce like a young couple having orgasm;

You teach zebras why they are black and white;

You surprise haughty deer, instructing them to have a sense of humor along with their fear.

When you are satisfied roaming in the jungle,

You pounce as the agent of the sun:

Catching pouncing clawing biting sniffing—

Such meek tiger achieves his purpose.

Glory be to the meek tiger!

Roaming, roaming endlessly,

Pounce, pounce in the artful meek way,

Licking whiskers with satisfying burp.

Oh, how good to be tiger!

Tiger

.

PHOTO BY CHÖGYAM TRUNGPA.

FOURTEEN

The King of the Four Seasons

A kingdom isn’t always a country. The kingdom is your household, and your household is a kingdom. In a family, you may have a father, a mother, sisters, brothers. That setup is in itself a small kingdom for you to practice and work with as its king or queen. Those who don’t have a family can work on how they schedule and conduct their own personal discipline properly and thoroughly.

I

T IS NECESSARY TO UNDERSTAND

the concept of the Great Eastern Sun in contrast to the setting sun. The setting sun is not abstract; it is something real that you can overcome. The setting-sun world is not Americana, nor are we saying that the medieval world is the world of the Great Eastern Sun. Rather, we are talking about overcoming frivolity and becoming a decent person.

The dot in space—first thought, best thought—automatically overcomes the setting sun. Just the thought of the setting sun is second thought, although it may sometimes be disguised as first thought. But it is not the best thought, at all. You have to give up all those second thoughts, third thoughts, and other thoughts up to even the eighth or ninth level. When you begin to give up, then you go back to first thought. When you almost despair and lose heart, that provides a sense of open space, where things begin anew.

The loneliness of the setting-sun world is very intense. Often people commit suicide because of it. Those who survive in the setting sun without committing suicide must maintain their “trips,” pretending that they are making a fabulous journey. I visited Esalen Institute some time ago. Everybody there was having a

groovy

time, as they would say there, trying to avoid reality. The whole setup is based on the avoidance of reality; therefore, you have a

groovy

time. It’s such a

groovy

place, such a fabulous place. You don’t ever have to do any work there. They would never ask you to use a shovel to dig up the earth and plant flowers in the garden. The flowers are there already for you to pick or wear in your hair. Such a

groovy

place with all sorts of schools of thought, schools of massage, and physical trainings of all kinds provided to make you younger—so that you can forget impermanence.

It is a place to be a teenager, even if you are ninety years old. Some of the older people actually behave like teenagers. In fact, they talk like them and think like them. The setting-sun philosophy is extremely appealing to some people, because it goes along with their own deception. To them, deception is referred to as

potential

. When people say that so and so has great potential, often they mean that so and so has very thick, dense deception. The dot in space cuts through hypocrisy of that kind and brings about the decorum that is based on truth and natural dignity. When you sneeze, you don’t have to apologize to anybody, just because you happen to have a body and you sneeze. Decorum is natural dignity and natural elegance that don’t have to be cultivated by means of deception. You don’t have to go to Esalen Institute to find it.

Togetherness

is another word for decorum. Such wonderful decorum is a sense of naturally fitting into the situation. You don’t have to tailor your outfit. It fits naturally, with dignity and beauty. That decorum, or genuineness, is the result of seeing the dot in space. From that, we begin to develop fearlessness, or nonfear. First, you see fear. Then, fear is overcome through the sense of decorum, and finally, fearlessness is achieved by means of seeing the dot in space.

Fearlessness is like a tiger, roaming in the jungle. It is a tiger who walks slowly, slimly, in a self-contained way. At the same time, the tiger is ready to jump—not out of paranoia but because of natural reflex, because of a smile and sense of humor. Shambhala people are not regarded as self-serious people. They see humor everywhere, in all directions, and they find beauty everywhere as well. Humor, in this sense, is not mocking others, but it is appreciating natural funniness.