The Cold War: A MILITARY History (63 page)

This very issue was highlighted by the French Pluton system, which was declared to be part of the French

pre-stratégique

force, intended to deliver a ‘final nuclear warning’ to an aggressor. The announced French intention was that in wartime most, if not all, Pluton regiments would join the French Second Army Corps in south-west Germany, where German territory is about 300 km wide. As Pluton’s maximum range was 120 km, this meant that even if the Plutons were sited well forward the missiles would have been launched against targets on West German territory – a concept over which the Federal government expressed some concern. As a result, at the end of a visit to West Germany in 1987, President Mitterrand gave an assurance that France would never deploy Pluton in this way, which raised the question of just how it could be used.

fn1

Specifications of the main types of battlefield nuclear weapon are given in

Appendix 27

.

fn2

This would have enabled the warhead to penetrate a considerable depth into most soil types before detonating, giving the resultant sub-surface explosion a considerable capability against underground bunkers.

fn3

The problem affected all weapons, including aircraft, conventional artillery, mortars, and so on, but was most acute for nuclear weapons.

34

Conventional War in Europe

THERE WERE MANY

possible scenarios for Soviet aggression in central Europe, but the worst case for NATO was a sudden attack launched by the in-place Warsaw Pact forces, which would have been reinforced covertly to the greatest extent Soviet commanders deemed feasible without being spotted by the West. The British assessed that the maximum that could have been used in an attack on the Central Front under such conditions was fifty-two divisions, of which twenty-three (nineteen Soviet and four Polish) would have faced NORTHAG and twenty-three (eleven Soviet, four Polish and eight Czech) would have faced CENTAG, with three East German divisions attacking Schleswig-Holstein. A further three East German divisions would have surrounded and attacked West Berlin, before moving on to further tasks.

A different scenario might have involved a Warsaw Pact attack to seize a specific and significant area in as short a time as possible, possibly using a major exercise in eastern Europe as the initial cover for such an operation. NATO experts believed that the Alliance would have detected such an exercise and called Simple Alert and Reinforced Alert, and a British study assumed that (with D-day being the day of the Soviet attack) Simple Alert would have been called on D-3 and Reinforced Alert on D-1, but this seems excessively optimistic. Even if it was correct, however, the Warsaw Pact would have started to attack well before NATO mobilization was complete, and the prospects of reinforcements such as from the UK to West Germany or Denmark reaching their deployment positions in time would have been very slim.

Some pretext for the attack would have been concocted, and the military moves would have been accompanied by messages to Western governments and to non-NATO nations that this was a limited attack with restricted aims. If the Warsaw Pact forces had achieved these limited aims and then halted, they would have placed NATO in a major dilemma, even supposing that

members

of the Alliance had been unanimous in their reactions to the initial attack. NATO’s first aim would have been to contain and halt the Soviet attack, while exerting heavy diplomatic pressure in an effort to force the Soviets to withdraw. The most serious possibility for NATO would have been to counter-attack immediately using tactical nuclear weapons, but it is highly questionable whether this would have been feasible, since public opinion in many Western countries could have been opposed to such a move. In particular, the West Germans would have been in a major dilemma, since it would have been they who had lost territory, but it would have been Germans who would bear the brunt of the casualties from a retaliation. If, eventually, the Soviets had withdrawn to their side of the Inner German Border under some face-saving pretext, they would have lost little, apart from a few hundred casualties. A second option would have been to sit tight and challenge NATO to oust them.

THE WARSAW PACT ATTACK PLANS

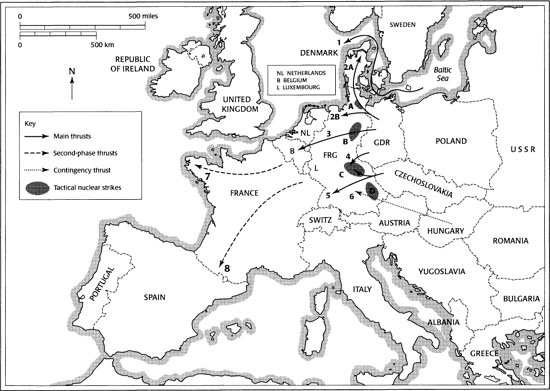

In the mass of documents released since the end of the Cold War, no evidence has been found of any Warsaw Pact defensive plans, except for a few formulated in the final three years, after President Gorbachev had insisted that the General Staff prepare them. Instead, all plans concentrated on a series of massive attacks, which were aimed at securing Soviet control of the entire west-European land mass. According to Soviet and East German planning documents, the major plan for the Central Front aimed at reaching the German–French border in between thirteen and fifteen days, and then of overrunning France so that the leading troops arrived at the Atlantic coast and the Franco-Spanish border by the thirty-fifth day. The attack would have been conducted by five, possibly six, ‘fronts’ (see

Map 3

, to which the numbers/letters refer):

1

• Jutland Front (2). This front was to advance northward through Schleswig-Holstein, across the Kiel Canal, and then on up through Jutland (2A). The Danish island of Bornholm would also have been captured. This would have opened the Belts (thus enabling the Soviet Baltic Fleet (1) to sail into the North Sea), closed the Baltic to NATO naval forces, and obtained valuable forward airfields for use in the land battles on the Central Front and in the naval battles in the North Sea. The advance along the Baltic coast would have been aided by amphibious assault forces from East Germany, Poland and the USSR, and possibly also by paratroops.

• Coastal Front (2B). The Coastal Front would have initially followed behind the Jutland Front attack and then broken away to swing south of Hamburg and along the northern edge of the North German Plain, with its right flank following the line of the North Sea coast. This would have secured the ports of Bremerhaven, Wilhelmshaven, Emden and Rotterdam (closing them to NATO maritime traffic), and secured the right flank of the main attack.

The Soviet Attack Plan

Note: Adapted from

Militärische Planungen des Warschauer Paktes in Zentraleuropa: Eine Studie

, Federal Ministry of Defence, Bonn, February 1992.

• Central Front (3). The main axis of this attack would have been across the North German Plain along the line Braunschweig–Hanover–Bielefeld–Hamm, then on through the northern edge of the Ruhr and thence to Aachen, Maastricht and Liege to the French Channel coast.

• Luxembourg Front (4). This advance would have begun in Thüringia and passed through the Fulda Gap, crossing the Rhine north of Frankfurt and then moving on towards the French cities of Reims, Metz and Paris.

• Bavarian Front (5). This attack would have originated in Czechoslovakia and swept through Bavaria and onward through Baden-Württemburg, over the Rhine and then into France.

• Austrian Front (6). Plans existed for a sixth front, which would have been mounted from Hungary, advancing through eastern Austria and on past Munich, with its left flank passing through Swiss territory to the south of the Bodensee (Lake Constance). This appears to have been a contingency plan, depending on whether or not the forces were required for operations in Italy, Greece and Yugoslavia.

Once west of the Rhine, two major thrusts would have been made towards the Atlantic coast (7) and the Spanish border (8).

The Forces Involved

The forces involved in these massive attacks would have totalled sixty divisions, of which some thirty-eight would have been Soviet, including a Naval Infantry brigade. Other Warsaw Pact forces were, however, an integral part of the plan. The East Germans would have contributed eight divisions to the Jutland, Coastal, Central and Luxembourg fronts, with a further three divisions being responsible for attacking and taking over West Berlin.

fn1

The Polish army would have contributed six divisions to the Jutland and Coastal Fronts, plus an amphibious assault brigade to take part in the landings along the Baltic coast. Czech forces would have contributed four divisions to the Bavarian Front, and, had it been activated, some Hungarian divisions would have been allocated to the Austrian Front. Coming up fast from the east would have been second- and third-echelon Soviet forces from Belorussia and the Ukraine, having first been brought up to war strength by mobilization.

It appears that the non-Soviet forces would not have been used in the advance into France. The East Germans, once their main operational missions had been accomplished, were required to impose military control on West Germany, with the immediate priority being to ensure that the territory could be used as an advanced operational and logistic base for continuing Soviet operations further West. The East Germans would presumably have been helped in this by the Czechs and Poles, since the task would have been enormous, involving, among many things, the imposition of military government, securing NATO prisoners of war, restoring of essential services, controlling refugees, and isolating nuclear-contaminated areas.

In these plans it was intended to use nuclear weapons as an integral part of the attacks, even if NATO did not use them first, and many targets had already been selected. The main attacks on the Central Front would have been allocated 205 Scud rockets at army level and 380 short-range missiles at divisional level, with 255 nuclear bombs carried by aircraft; of these, the first-echelon armies could each have expected some twenty Scuds, fifty-five short-range missiles and ten air-delivered bombs. Yields would have varied between 3 kT and 100 kT, and the weapons would have been targeted on NATO nuclear-weapons and nuclear-support facilities, airbases, headquarters and communications centres, troop concentrations and naval bases.

fn1

These would almost certainly have overrun West Berlin very rapidly, and then, having handed over mopping-up operations to a reserve formation, moved westward to reinforce one of the northern fronts.

35

If Nuclear War had Come

IN CONSIDERING THE

Cold War, it is inevitable to speculate what might have happened if, events having worked out differently, war had broken out, leading to a nuclear exchange. Such an assessment is beset by difficulties, one of the most important being that only two atomic bombs have ever been dropped in anger. There were many subsequent tests, but these were, almost without exception, conducted in clinical conditions, and were concerned with small numbers of representative objects, such as houses, tanks, aircraft and ships. In particular, there is no precedent from which to judge how populations or the military might have reacted. When the A-bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the unsuspecting populations had no idea what had caused the disasters that had befallen them, and their subsequent behaviour gave little guidance as to how the survivors of a massive nuclear attack might have behaved; equally well-researched studies have reached conclusions varying from total discipline to total anarchy.

fn1

THE US STRATEGY FOR NUCLEAR WAR

The original US nuclear-war plans were prepared at a time when bombers predominated, atomic bombs were in very short supply, and there was a lack of co-ordination of plans. The 1947 plan concentrated on destroying the war-making capability of the Soviet Union through attacks on government,

political

and administrative centres, urban–industrial areas and fuel-supply facilities. It was to have been achieved by dropping 133 atomic bombs on seventy Soviet cities in thirty days, including eight on Moscow and seven on Leningrad.

1

This plan was ambitious, to say the least, primarily because the USA possessed a total of only thirteen atomic bombs in 1947 and fifty in 1948.

2

In May 1949 a new plan, named Trojan, required 150 atomic bombs, with a first-phase attack against thirty cities during a period of fourteen days. Then, also in 1949, came another plan, named Dropshot, in which a war in 1957 would be centred on a thirty-day programme in which 300 atomic bombs and 20,000 tonnes of conventional bombs would be dropped on about 200 targets, with the atomic bombs being used against a mix of military, industrial and civil targets, including Moscow and Leningrad.

3

All these plans included substantial quantities of conventional bombs and were essentially continuations of Second World War strategies. Interestingly, even as early as 1949, planners were earmarking command centres for exemption from early strikes (‘withholds’ in nuclear parlance), so that the Soviet leadership could continue to exercise control.

Up to about 1956 the US authorities based their plans on intelligence which was far from complete and, as a result, they deliberately over-estimated their opponent’s strengths. In 1956, however, the Lockheed U-2 spy plane started to overfly the USSR, and this, coupled with more effective ELINT and SIGINT, meant that a more accurate picture was obtained.