The Classical World (80 page)

Read The Classical World Online

Authors: Robin Lane Fox

Domitian’s insecurity and love of ‘luxury’ were intolerable and like Nero he was murdered by his own palace-attendants. As he had no sons, there was scope for those in the plot to choose their own candidate. Revealingly, they chose the elderly Nerva, sixty years old, a noble patrician by birth, a respected senator and also without sons. The full Senate then approved their choice, someone who was, at last, a mature insider. It was not just that he had written admired Latin elegies in his youth. Rather, three times in the last thirty years, Nerva had been honoured highly after crises in the emperors’ management of affairs. His ancestors had been lawyers and he himself probably had a knowledge of law. In 71 he had been honoured most remarkably with a consulship: perhaps it was a reward for co-ordinating work on the ‘law’ for Vespasian’s powers in the previous year.

It is Nerva, not Titus or Vespasian, who reallyis the ‘good’ emperor. At last, senatorial contemporaries could proclaim the reconciliation of ‘freedom’ and the Principate. Nerva’s coins publicized ‘Public Freedom’ and an inscription set in the ‘Hall of Liberty’ at Rome read, ‘Liberty Restored’. Of course the system was not undone, but the popular assemblies at Rome did meet and exercise ‘liberty’ by passing laws. The hateful Domitian’s statues were melted down and his name ‘abolished’ on monuments. But Domitian’s appointments and rulings did have to be confirmed: too many people, including senators, had gained from them.

Besides promoting freedom, Nerva understood the importance of standing out against injustice and luxury. He corrected the harsh effects of the inheritance tax on new citizens and extreme applications

of the Jewish tax on Jews and sympathizers. The accusers in tax cases in his provinces could no longer be the judges too; there were no longer to be prosecutions for slandering the emperor, and philosophy was granted public support. Spectacularly, Nerva sold off land, even clothing, in imperial ownership. He forswore ‘luxury’, and also directed ‘liberality’ towards poor people in Italy: money was set aside to buy them plots of land. It was all good policy, but the imperial system did not rest only on goodness. There were the all-important soldiers and the guards in Rome.

Optimistically, Nerva’s coins proclaimed ‘Concord of the Armies’. However, the troops still liked Domitian, who had raised their pay, and in autumn 97 the Praetorian guards forced Nerva to approve a brutal execution of Domitian’s murderers. Someone more robust and military was manifestly needed. There was talk later of an outright coup but it was probably with Nerva’s own agreement that he announced a soldier as his adopted heir. The choice was Trajan, a man from a colonial settlement in Spain with a distinguished military father and experience with the armies in Germany. Behind the adoption plan we can detect two senators, one of whom was Frontinus, a former governor of Britain, distinguished for his efforts in Wales, and the acknowledged authority on Rome’s aqueducts.

The new pair of Nerva and ‘son’ might have worked very well for some years, each complementing the other. However, after three months Nerva unexpectedly died. In the footsteps of Vespasian’s Flavian dynasty, he bequeathed to his successor a governing class at Rome which, inevitably, was much changed in tone and composition. Not only had prominent Greek-speakers from the East entered the Senate (Domitian’s patronage had been important here, in keeping with his cultural tastes). Vespasian, from ‘little Italy’, had helped to replenish the Senate with yet more members from ‘little Italy’ too. The legal statement of his powers had been acceptable to these new men, but then Domitian had elevated himself too far above them. By defying their moral values and standards, Domitian had shown up both the strengths and limitations of what such people stood for. After his death senators were quick to dare to condemn him, but they were equallyquick to justify themselves and their recent compromises. For there was so much which was best left unsaid. As a principled

dinner-guest once aptly remarked to Nerva, if the worst of Domitian’s informers had still been alive, they would doubtless have been dining in their company with Nerva too.

9

The Last Days of Pompeii

If you felt the fires of love, mule-driver,

You would make more haste to see Venus.

I love a charming boy, so I beg you, goad on the mules; let’s go.

You have had a drink, so let’s go. Take up the reins and shake them.

Take me to Pompeii where love is sweet

.

Inscribed in the peristyle courtyard of House IX.V.ii, Pompeii

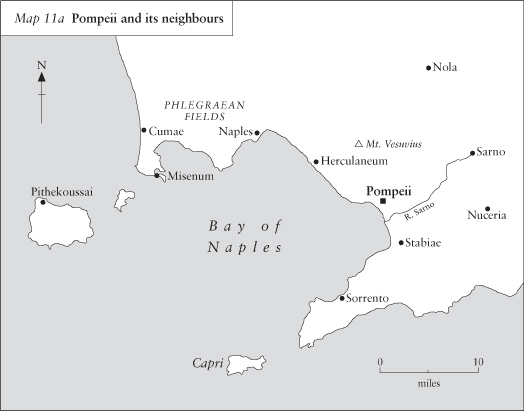

The new men promoted from the towns of Italy in the 70s were credited with a new frugality and restraint. For a glimpse of their values in action, we can turn to archaeology’s great survivors, the remains of Pompeii and nearby Herculaneum. On 24 August 79 Mount Vesuvius erupted in Italy, near Naples. A thick shower of dust and pumice ascended over the surrounding territory, accompanied by earthquakes, flames and a cloud shaped like a tree (said the eyewitness Pliny), with a crown of branches like an umbrella pine, a variety which is still so familiar around the ruins. This cloud rose up to a height of some twenty miles above the mountain, and, if we compare the similar recent explosions of Mount St Helens in north-west America, we have to reckon that the explosions in Vesuvius had had a force five hundred times greater than the atom bomb at Hiroshima. At Pompeii we can trace the effects in three awful stages. First of all, a shower of white pumice, some three yards deep, blocked the daylight, then greypumice blackened streets and buildings. On the following morning, 25 August, by about 7.30 a. m., a great ‘burning cloud’ of hot gas rolled into the streets, suffocating and burning those who had stayed or been trapped. This very powerful ground surge was

followed by the pyroclastic flow of hot liquified rock and pumice which destroyed buildings and rolled on far past the town; then ‘surge’ and ‘flow’ came in four waves of increasing ferocity until 8 a. m. They caused the death of the spectacle’s most learned observer, Pliny the Elder: as his nephew’s letters recall, Pliny had boated across the Bay of Naples to have a closer look. Inside the town, bodies of the dead continue to be found. They range from mules, trapped by their mangers near the millstones which they used to turn, to the young lady, dressed in jewels, whose breasts had left their imprints in the mud where she died. At Herculaneum, the surge and flow struck earlier in the morning and hit the town in six waves, running out into the sea. The town was buried even more deeply than Pompeii and not, it now seems, from the secondary effects of rain and floods. The entire disaster was massive, and we can well understand why it was a strain and expense on the Emperor Titus’ first year in power.

Pompeii and Herculaneum were close to the Bay of Naples, where so many of the grandest Romans had built spectacular villas. Even at the height of the Bay’s luxury (in the first century

BC

), neither place had been a city of the first rank; by the 70s the Bay had lost a little of its predominance. Pompeii, the better known, would have covered about 350 acres and contained a population of perhaps 8,000–12,000 in its last days. The town was laid out on a plateau of volcanic lava, the relic of a former eruption, and various types of volcanic rock had helped to build it. But the inhabitants did not know the risk they ran: Vesuvius’ last eruption was more than a thousand years in the past, and the stone probably seemed harmless. Pompeii itself had grown up in layers, through clear phases of history since the sixth century

BC

: Etruscan (with Greeks), Samnite, colonial Roman (from 80

BC

onwards) when Cicero had had one of his houses there. By

AD

79 its roots, like modern London’s, were at least two centuries old, and the residents continued to build and rebuild over them right until the end.

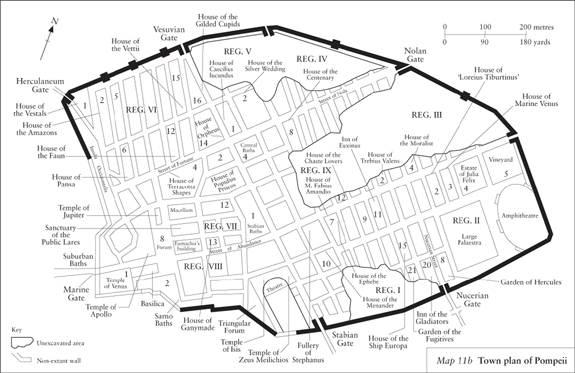

One result is that the best-preserved ancient town is in many ways still hard to understand. It never stood still, and after the fatal eruption the looting began promptly. It has been continuing ever since excavation began again in the 1740s. Fortunately, one-third of Pompeii has been reserved for future archaeology, although so much has been destroyed, sold or dispersed meanwhile.

One side of Pompeian life seems appealingly modern. There was a planned street-system to exclude wheeled traffic from areas in the town centre. There are well-preserved wine-bars with ‘pub signs’ of a phoenix or a peacock. There are theatres and a so-called ‘sports complex’ and a special market-building for fish, meat and delicacies for people doing the shopping. Many of the houses have big paintings or frescos on their walls, and there was a definite cult of ‘house and garden’.

Trompe l’

œ

il

paintings seem to enlarge the gardens’ space and even show exotic birds and the flowers which grew in pots and borders, whether roses or bushes of myrtle. Owners would eat out around a shaded table in their ‘room outside’: 118 pieces of silver were found stored in one big house’s basement, including a set for dinner parties of eight people.

1

There were also graffiti and well-written inscriptions. Forty-eight graffiti of Virgil’s poetry have been found (including some in a brothel). On the street-fronts of the bars, houses and public

buildings, election-posters – some 2,800 in all – advertised support for particular candidates for civic office. About forty of these posters name women’s support, although women themselves could not vote.

2

Through painted portraits we feel we know these people, the young ladies with a pen to their lips and blond, classicizing features, or the men beside them with dark eyes and a shifty sort of look. But so much of this time warp is not our idea of a cosy town at all. Images and shrines of the gods were all over the place, quite apart from the big formal temples on the main forum. Slaves were essential to the households and crafts, although the loss of the buildings’ upper storeys makes it hard to visualize where many of them lived. Ex-slaves, freed-men, were also essential to the economyand the social structure. After being freed, most of them still worked for their former owners (as they did in Rome) who could thus profit ‘from’ business without being tied down ‘to’ it. There were no high-street banks (money lending was a personal transaction) and there were no hospitals or public surgeries. There were brothels, but no moral ‘zoning’ into red-light districts. There were no street-signs, either. There are well-preserved lavatories behind discreet partitions, but two, even six, people would be accommodated on them side by side, wiping their backsides with communally provided sponges.

Despite the theatres, the main sports complex was an amphitheatre for blood sports, both human and animal: it is the earliest one to survive, dating back to the 70s

BC

when Pompeii’s population had been changed by the arrival of Roman veteran-colonists. Gladiatorial shows are announced and applauded in many of the town’s surviving graffiti: ‘the girls’ idol, Celadus the Thracian gladiator!’

3

Nor were the town’s big houses the inward-looking centres of privacy which we now cherish. Like a Roman’s, a Pompeian’s home was not his castle and ‘home life’ was not a concept which men prized for its own sake. It is not that the Roman family was an extended family by definition, somehow sprawling in one house across generations and between siblings. It was nuclear, like ours, but it was embedded in a different set of relationships. If the head of the household, or

paterfamilias

, was an important person, he was also a patron to many dependants and ‘friends’ who both gave and expected favours. Every morning, a string of visitors went in and out of the house, which was itself a sort

of reception centre. Many of the older, bigger houses thus gave visitors an impressive view through them from the entrance, as they looked down the straight main axis of their central rooms: this axis was supported on huge timber cross-beams, some thirty feet long.

In the last decades of the city, this type of plan was far from universal. Big houses now included workshops for craftsmen, shops or even bars adjoining the street, obscuring the ‘view through’. The Latin word

familia

included household slaves, and in these workspaces they and their owner’s freedmen would be put to profitable use. Inside, in the household proper, we would be struck by the relative absence of furniture, the multi-purpose use of many of the rooms and the consequent absence of our ideas of privacy. Even the plants in the bigger gardens were often there for their economic value, not for useless gardening. In the southern sector, houses with quite large vineyards inside their plots have now been excavated, while even roses might be grown for the important industry of scent.