The Classical World (19 page)

Read The Classical World Online

Authors: Robin Lane Fox

By

c.

500

BC

the Roman community numbered probably about 35,000 male citizens, and its territorial control already extended southwards as far as Terracina, on the coast about forty miles from Rome. Although its male citizenry was probably bigger than contemporary Attica’s, culturally it was still a humble place onto which a strong rejection of ‘luxury’ was only later projected by legends. But values of ‘freedom’ and ‘justice’ were prominent. The reforms of Servius were admired by later Romans as a source of ‘freedom’: at the time the most urgently desired freedom was surely freedom from the monarchical rule of a king. Freedom from kings continued to be the political value of all noble Romans, long after the ending of monarchy. Roman nobles, not the people, deposed the last tyrannical ‘king’ in 510/9 Bc, at a time when aristocrats in most Greek cities had already deposed their tyrants.

What followed, however, was a decidedly popular demand for justice. In 494

BC

, probably during a military levy, some of the common people (the plebs) are said to have decamped to a hill outside Rome and ‘seceded’ from their superiors at a moment when their help was needed as soldiers. One of their concerns was protection against the abuse and physical oppression of the powerful, the sort of abuse which, a hundred years earlier, had been curbed by Solon in Attica.

Defence of these interests was therefore assigned to a new type of magistrate, to be known as ‘tribunes of the plebs’. On hearing of an individual’s ‘cry for help’ these sacrosanct officials could now physically interpose themselves between the aggrieved citizen and his oppressor. In later tradition, the burdens of debts and dues were also said to have been resented at this time, and demands for a distribution of land followed. In broad terms, these demands, too, would have been familiar to Greek observers. In the 450s the collection and publication of the laws met a further demand for justice, which arose as much from Rome’s ruling class as from their social inferiors. At Athens, in the 620s, the publication of the first Athenian written laws can be traced to similar social pressure.

In early Rome, then, we can detect some of the dynamic which had precipitated changes in parts of early Greece too. Of course, the Romans spoke their own ‘barbarian’ Latin, worshipped their own gods and went their own way without Greek guides. If Romans really did ever visit Athens to inspect their law-code, the Athenians certainly left no record. Rome was of no interest to them. What interests us, however, is the Athens which these Romans were supposed to have visited.

The Classical Greek World

Among the Greeks, individuals determined to stand out from all others were characteristic, and the concept of personal power became paramount; depending on circumstances, they ranged from the most devoted servants of the

polis

to those who committed the greatest crimes against it. This

polis

itself, with its mistrust and its narrow ideas of equality on the one hand, and its high expectation of integrity (

aret

ē

) from individuals on the other, drove gifted men to follow this course, which might lead them to reckless greed and possibly to megalomania. Even Sparta, which tried to contain potentially many-sided individuals within the strict bounds of their usefulness to the State, only succeeded in producing a breed of ruthless hypocrites; as early as the sixth century there is the terrible Cleomenes, then in the fifth, Pausanias, and finally Lysander. It is debatable whether this development was beneficial for the

poleis,

and whether in any case it was avoidable; but as a result the Greek world makes the impression of an immense wealth of genius both for good and evil.

Jacob Burckhardt,

Greek Civilization

(1898,

translated by Sheila Stern, 1988)

‘Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.’ No doubt, but like all truisms, this one offers little practical guidance. Vigilance against whom? One answer is to rest one’s defence on public apathy, on the politician as hero. I have tried to argue that this is a way of preserving liberty by castrating it, that there is more hope in a return to the classical concept of governance

as a continued effort in mass education. There will still be mistakes, tragedies, trials for impiety, but there may also be a return from widespread alienation to a genuine sense of community. The conviction of Socrates is not the whole story of freedom in Athens.

M. I. Finley,

Democracy Ancient and Modern

(1973), 102–3

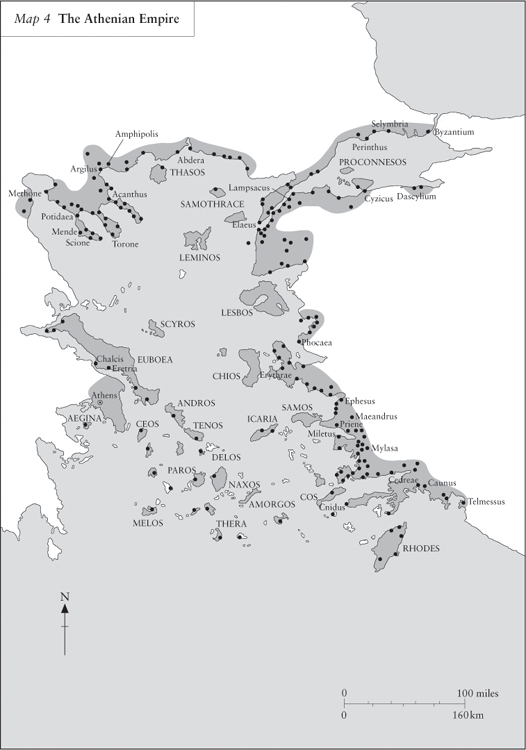

Conquest and Empire

‘I shall not revolt against the people of the Athenians either by guile or by trick of any kind, either by word or deed. Nor shall I follow anyone in revolt and if anyone does revolt, I shall denounce him to the Athenians. I shall pay to the Athenians the tribute which I persuade them (to assess) and as an ally I shall be the best and truest possible. I shall help the people of the Athenians and defend them if anyone does injury to the people of the Athenians, and I shall obey the people of the Athenians.’ This oath shall be taken by adult Chalcidians, all without exception. Whoever does not take this oath is to lose his citizen-rights and his property shall be confiscated.

Athenian treaty with Chalcis, 446/5

BC

For Megacles, son of Hippocrates and his horse as well

…

Inscribed potsherd, cast against noble Megacles at Athens (Cerameicus, Ostrakon 3015, first published in 1994)

Megacles, son of Hippocrates.

With a drawing of a fox on the run. Another such potsherd. The fox (alopex) is the voter’s own allusion to Megacles’ deme (Alopeke) and his ‘bushy-tailed’ duplicity, foxiness being

associated with treachery and pro-Persian sympathies. So, Megacles must run far away… (Cerameicus, Ostrakon 3815)

The Greek victories over barbarian Persians and Carthaginians were certainly related to the three major themes of this book. Both the

Carthaginians and the Persians displayed far more riches and ‘luxury’ than the Greeks in the city-states. They set out to destroy Greek political freedom and if victorious they would have substituted their own justice. But luxury was not the main reason why their armies failed. Freedom, rather, was the crucial value in the Greek victories, and its absence as a motivating force was a crucial reason for the failure of the Persians’ army and the Carthaginians’ mercenary force. The Greeks’ military innovations were important, too, the metal-armoured hoplites, especially the Spartans’, and the newly built Athenian ships. But they, too, were connected with underlying values. In the 650s

BC

the introduction of hoplites had become connected with a demand for justice which the tyrants and lawgivers then addressed. The supreme source of hoplites was the Spartans’ system and initially it, too, addressed the stresses caused by luxury and the need to stay ‘free’ from tyranny.

A different theme, to be repeated in the later rise of Macedon, was the luckily timed discovery of a source of precious metal: the silver in Attica. In Sicily, there was no local source of silver, but the Sicilians did not win by building a new fleet. The Athenians did, and the silver was crucial: new supplies of precious metal, newly mined or taken through conquest, are important in the power-relations of ancient states. They made states rich, far more so than a rise in their manufacturing or any export-led growth. But mining-strikes had to be exploited, and here the Athenians’ supply of slaves was crucial: they enabled the metal to be mined quickly. The ships, once built, then had to be rowed with commitment and here, too, the Athenians’ distinctive class-structure was important. All their citizens, the lower classes included, were willing to combine and fight for their recently acquired democratic freedom. The Spartans, lacking democracy, could never have mobilized such numbers of committed citizens. By contrast, several of the Greek communities which were under aristocracies or broader oligarchies treacherously took the Persian side. There were exceptions, not least the Corinthians, but one reason why Greeks ‘Medized’ was that the noble Persians seemed more congenial than the risk of a hostile democracy emerging at home.

Class, then, played a relevant part in the Greek victories, along with a material windfall (the silver) and no end of good luck (the weather

at sea). There were also, of course, the Greeks’ values and the resulting ambitions of their citizens. For the Greek victories over barbarian invaders were followed up quite differently in the West and East. In the West, the defeated Carthaginians were left alone with their own sphere of ‘domination’ (

epikrateia

) in western Sicily. There was no attempt by the Sicilian Greeks to take revenge in north Africa on Carthage herself. In the East, the Greeks went on the offensive. The Hellenic Alliance had sworn oaths of alliance in the dark days of the Persian advance and it was now enlarged and launched into a ‘Hellenic War’, the sequel to the ‘Persian War’.

The declared aim was to punish the Persians for their acts of sacrilege in Greece (the burning of temples, especially at Athens) and to liberate fellow Greeks in the East who were still under Persian rule. At first, nobody could have assumed that the Persians would not soon return for revenge of their own. It required another Greek victory in 469

BC

at the mouth of the river Eurymedon on the south coast of Asia (now the Gulf of Antalya) to deter a big Oriental fleet which was intended to regain the sea for the Persian king. Liberation of the eastern Greeks was also patchy. Some of the Greek city-states in Asia were still in the Persian king’s gift as late as the mid-460s. Liberation did, however, make a difference when it happened: many of the eastern Greeks were freed from tyrants and satrapal rule in return for a modest yearly payment to the Greek allies’ Treasury. There were also persistent attempts to free Cyprus, where Greek rulers were sympathetic to them, but Phoenicians were still embedded in the ‘New Town’ of Kition on the south-east coast of the island. These attempts began heroically in 478, but during a later one in 459

BC

the allied Greek forces were diverted by a request for help from a rebel ruler in nearby Egypt. If Egypt could be detached from the Persian Empire, it would be a spectacular gain, not least for the mainland Greeks’ grain-supply and economy. In fact, the large Greek expedition to Egypt failed dismally after a five-year campaign. In 450 one final attempt to free Cyprus failed too and the island was then ceded to the Persian king in return for an agreement that Persian ships would not enter the Aegean and that the Greek cities in Asia would no longer be tribute-paying and under Persian rule. This ‘peace’ was fragile, but it was a significant gain nonetheless. The east Greek city-states now paid

tribute yearly to the Athenians instead of to the Persian king, but they were free, at least in theory, from Persian political interventions.

In the Greek West, the Greeks’ trouncing of Carthage’s forces in 480 was followed by a decade of splendour, not for democracy but for Sicily’s Greek tyrants. Their major tyrant-families intermarried, and so the main political tensions were those between the tyrants’ family members: we can see evidence of them even in the most famous surviving work of art in their honour, the bronze Charioteer at Delphi. Significantly, its dedicatory inscription by one brother was changed and replaced by another brother’s name. In mainland Greece, however, the years of ‘punishment’ for Persia coincided with a real political choice, the continuing split between two opposed styles of Greek life: the harsh oligarchy of Sparta’s military peer group and the increasingly confident democracy of the Athenians. Feebly, the Spartans presented the governments which they favoured in their allied cities as ‘iso-cracy’ (‘equal rule’), a response to the Athenians’ proud and very different ‘democracy’.

1

To placate their allies, since

c.

506

BC

the Spartan kings had had to agree to discuss all proposed allied wars in a joint synod.

Against the Persians in Greece, nonetheless, the two powers had sunk their differences. From 478 to 462 the Athenians then led the Hellenic Alliance by sea, the Spartans by land, as the Spartans lacked any trained fleet and any coinage with which to pay one. They could hardly risk recruiting their helot-serfs as fighting oarsmen. On many fronts, they ran into severe problems. Their kings were brought to trial in Sparta after military failures or complaints about their policies. Even the young regent Pausanias, hero of the Persian Wars, was dismissed and put on trial. Within the Spartans’ southern Greek orbit, there was continuing opposition among the Arcadians on their doorstep; democracy began to infect important allies in the Peloponnese; in 465 a major revolt broke out among the Spartans’ dependent helots. They were not alone. In the West, in the late 460s, the Greek cities also confronted a major war against non-Greek Sicels who lived beside them near Mount Etna. It persisted until 440 and created a Sicel hero, the leader Ducetius, who founded a lasting settlement, Kale Akte (Fair Coastline). But unlike the Sicels, Sparta’s helots were oppressed fellow Greeks, and so the long Spartan serf-war was the more dangerous of the two. After three years, under the terms of the Hellenic Alliance,

the Spartans summoned Athenians to help them, because they valued their general Cimon’s skills in siege-warfare. The summons was a turning point. Before long, in Sparta, Athenian soldiers realized the uncomfortable truth, that the Spartans, supposedly their fellow liberators, were suppressing their neighbouring Messenian Greeks. Many of them had never realized this truth about a ‘helot’. The Spartans then dismissed their Athenian helpers because they feared their audacity and capacity for causing a revolution. This cardinal rebuff broke up the Hellenic Alliance and soon led to war in Greece between ‘the Athenians and their allies’, as the old League became, and ‘the Spartans and their allies’, what we now call the ‘Peloponnesian League’. On their return, the Athenians ostracized the pro-Spartan Cimon, adopted reforms which further entrenched democratic principles in their constitution and accepted alliance with the Spartans’ allies, the Megarians, and a traditional Spartan enemy (Argos). For some fourteen years war would persist between the Athenians and, in particular, Sparta’s allies, the oligarchic Corinthians.