The City of Dreaming Books (35 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

I struggled to regain my composure. The Booklings’ sense of humour frayed my nerves. ‘Not bad,’ I said. ‘I had a good authorial godfather.’

‘Then you’ll find this entertaining. The thing is, we could introduce you to all the Booklings by their chosen writers’ names, one by one, and that would be that. Right?’

‘Right,’ I said. I hadn’t a clue what he was getting at.

‘But that wouldn’t be any fun and you’d have forgotten the names by tomorrow, or got them all mixed up. Right?’

‘Right.’

‘So we’re now going to introduce each Bookling in turn, and you must

guess

his name.’

guess

his name.’

‘What?’

‘You’ll memorise the names far better that way, believe me. This is how it works. Every Bookling selects a passage from his writer’s works - one he believes him to have written when the Orm was flowing through him with particular intensity. He will then recite the said passage aloud. If you’re good at Zamonian literature you’ll identify it in most cases, but if you’re bad at Zamonian literature you’ll make a terrible ass of yourself. Although I said “he” in every case, I should add that our writers can be male or female. That’s what we mean by Orming.’

I gulped involuntarily. How good was I really at Zamonian literary history? How high were the standards that applied here?

‘But I must warn you,’ Al whispered. ‘Many of our number select their passages according to very strange criteria. In some cases I suspect they deliberately choose atypical examples to make it harder to guess their names.’

I gave another involuntary gulp. ‘Why don’t we simply introduce ourselves by name and leave it at that?’ I suggested. ‘I’m pretty good at remembering names.’

But Al had already turned away. ‘Orming time! Orming time!’ he called in a thunderous voice. ‘Everyone gather round for Orming!’

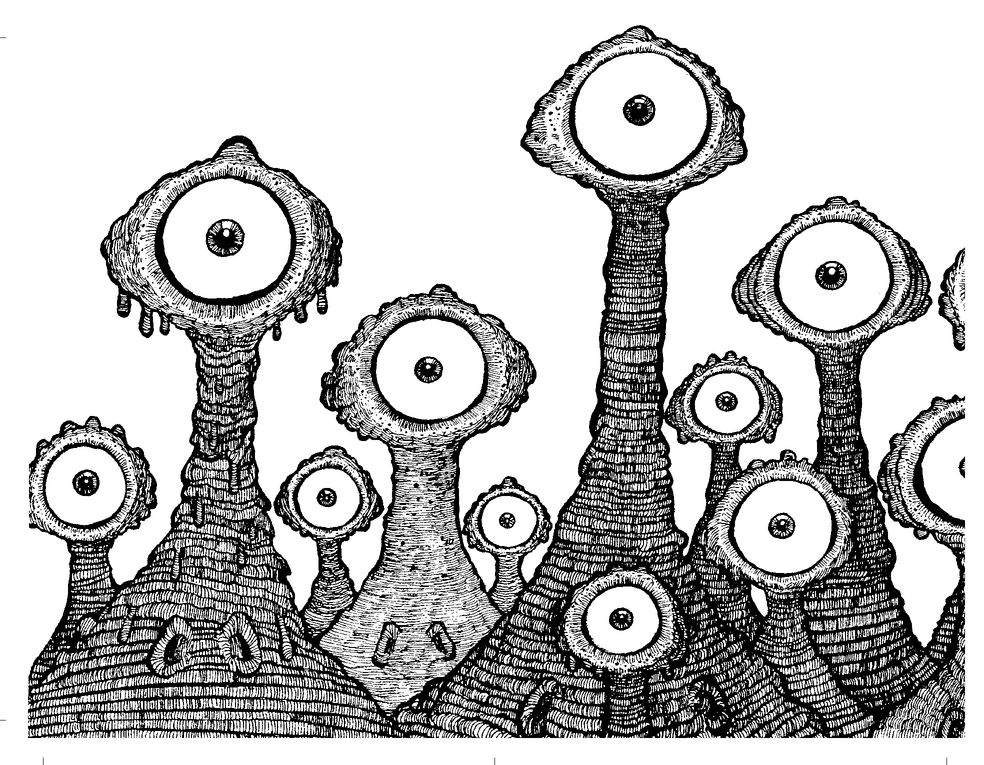

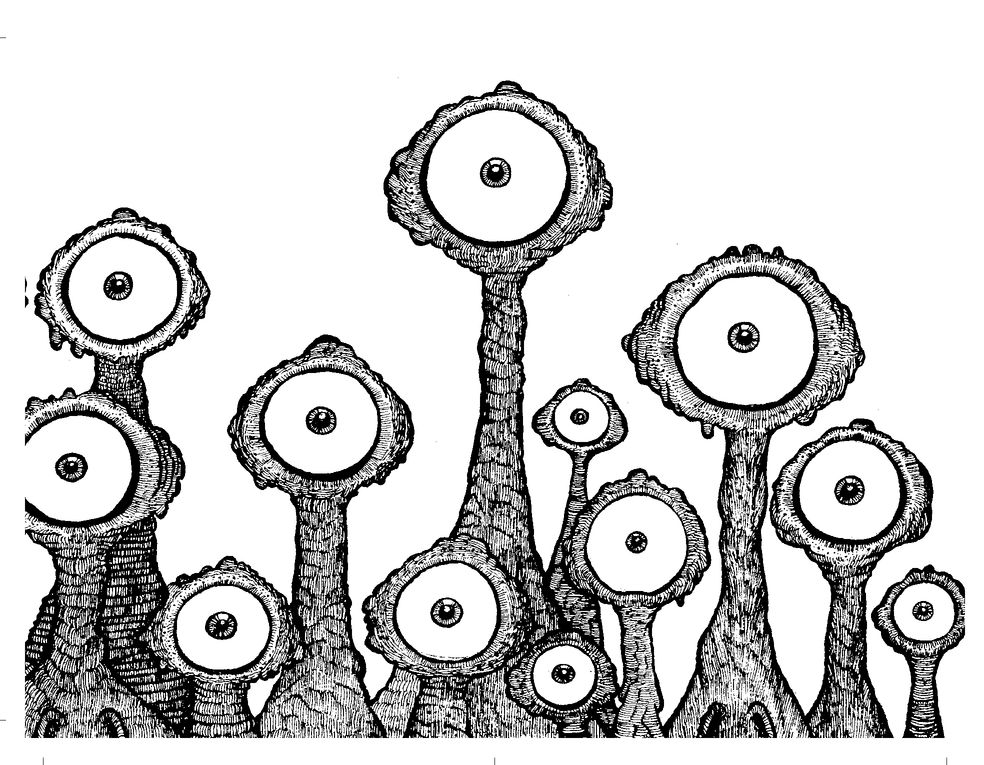

He led me down from the machine to the floor of the cavern, where the Booklings formed a big circle round me. Escape was impossible. They were now at liberty to stare at me without embarrassment, which they did, fixing me with their glowing, piercing cyclopean gaze. I felt simultaneously naked and like a specimen under a microscope. The hubbub had died away, to be replaced by an expectant hush.

‘This, my dear fellow Booklings,’ Al cried, puncturing the silence, ‘is Optimus Yarnspinner. He’s an inhabitant of Lindworm Castle and a budding author.’

A murmur ran round the assembled company.

‘He was dumped in the catacombs against his will and lost his way. To save him from certain death, Wami, Dancelot and my humble self’ - Al inserted a brief pause, presumably to allow someone to dispute the description ‘humble’, which no one did - ‘and, er, I have decided to grant him temporary membership of our community.’

Polite applause.

‘That being so, it will be our pleasure to have a genuine author in our midst for the next few days. He hasn’t published anything yet, but we all know that this is only a matter of time. He hails from Lindworm Castle, after all, so it’s his destiny to become an author. Indeed, we may even be able to make some small contribution to his literary career.’

‘You’ll make the grade!’ a Bookling yelled at me.

‘Sure,’ cried another. ‘Just write - the rest will come by itself!’

‘Practice makes perfect!’ shouted someone right at the back.

I was becoming rather embarrassed by the whole situation. Couldn’t they at least get on with the confounded Orming?

‘Good,’ cried Al. ‘Now you know his name: Optimus Yarnspinner! May it one day be emblazoned on the backs of scores of books!’

‘Scores, scores, scores!’ chanted the Booklings.

‘But. . .’ Al cried dramatically. ‘Does he know

our

names?’

our

names?’

‘No!’ cried his listeners.

‘So what shall we do about it?’

‘Orm him! Orm him! Orm him!’ they bellowed.

Al made an imperious gesture and they all fell silent.

‘Let the first one step forward!’ Al commanded.

Nervously, I gathered my cloak around me. A tiny, yellowish Bookling came and stood in front of me.

He cleared his throat and, in a voice quivering with emotion, declaimed,

‘Hear the loud Bookholmian bells -

brazen bells!

What a tale of terror, now, their turbulency tells!

In the startled ear of night

how they screamed out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak,

they can only shriek, shriek . . .’

brazen bells!

What a tale of terror, now, their turbulency tells!

In the startled ear of night

how they screamed out their affright!

Too much horrified to speak,

they can only shriek, shriek . . .’

Wait a minute, I knew that poem! Its rhythm was unmistakable - it was a unique and masterly example of Zamonian Gloomverse. It was, it was . . .

‘You’re Perla la Gadeon!’ I exclaimed. ‘That’s “The Burning of Bookholm”! A poetic masterpiece!’

‘Damnation,’ growled the Bookling, ‘I should have chosen something less popular!’ But he beamed with pride at having his name guessed so quickly. The other Booklings broke into subdued applause.

‘That was easy,’ I said.

‘Next!’ called Al.

A green-skinned Bookling stepped forward and gazed at me sadly with his red-rimmed eye. Then he spoke in a thin, brittle voice:

‘Bid the last few grapes to fill and ripen;

give them two more days of weather fine,

force them to mature, thereby instilling

all their sweetness in the heady wine.’

give them two more days of weather fine,

force them to mature, thereby instilling

all their sweetness in the heady wine.’

Hm. A wine poem, but not just any old wine poem. One in particular.

The

wine poem to end all wine poems, which recounted the terrible fate of Ilfo Guzzard. And that had been written by . . . ‘Inka Almira Rierre!’ I cried. ‘It’s the second strophe from his “Comet Wine”!’

The

wine poem to end all wine poems, which recounted the terrible fate of Ilfo Guzzard. And that had been written by . . . ‘Inka Almira Rierre!’ I cried. ‘It’s the second strophe from his “Comet Wine”!’

Inka bowed and retired without a word. Deafening applause.

‘Next!’ I said before Al could do so. My self-confidence was growing. I was beginning to enjoy Orming.

A purple-complexioned Bookling emerged from the crowd with majestic tread. Drawing a deep breath, he flung out his arms and cried: Before he could utter even one more syllable I levelled an accusing finger at him and said, ‘You’re Dolerich Hirnfiedler!’

Well, Dolerich Hirnfiedler was notorious for beginning every other poem with an ‘O!’. It was only an audacious shot in the dark on my part - many poets had done the same - but to my amazement the Bookling gave a shamefaced nod and withdrew. Bingo! I’d guessed his identity on the strength of a single letter! A murmur ran through the Booklings’ ranks and several of them glunked their teeth approvingly.

‘Next!’ Al called.

An albino Bookling with a watery red eye stepped forward.

‘How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

my soul can reach. When I behold the sight

of thy bowed head and mournful, careworn face

my spirits sink, beyond all power to raise,

and every day becomes perpetual night.’

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

my soul can reach. When I behold the sight

of thy bowed head and mournful, careworn face

my spirits sink, beyond all power to raise,

and every day becomes perpetual night.’

Good heavens, Bethelzia B. Binngrow! My authorial godfather had robbed me of many a night’s sleep by compelling me to memorise the lugubrious love poems of that half-demented Florinthian poetess. I still knew that one by heart.

But this time I decided to keep everyone on tenterhooks - to wait before shooting my bolt - so I pretended that this was a particularly tough nut to crack.

‘Phew!’ I said. ‘Gee, that’s difficult . . . it might be . . . no . . . or . . . no, he didn’t write any poems that rhymed . . . or it’s . . . just a moment . . . I can see a name. . . no, two names and an initial . . . they’re very faint . . . almost invisible . . .’

The Booklings groaned with suspense.

‘I do believe the mist is clearing . . . Yes! Now I’ve got it! You’re Bethelzia B. Binngrow! Barmy Bethelzia!’

The last words just slipped out. The Bookling whose identity I’d guessed emitted a resentful snort, turned on his heel and disappeared into the throng. Everyone broke into relieved applause. I wiped some non-existent sweat from my brow.

‘Next!’ cried Al.

A thickset Bookling with a pale-blue complexion elbowed his way through the crowd. One or two titters could be heard as he stationed himself in front of me.

‘A f-f-fish, a s-s-skeletal f-f-fish

l-l-lay on a r-r-rock.

How d-d-did it c-c-come

t-t-to b-b-be there?’

l-l-lay on a r-r-rock.

How d-d-did it c-c-come

t-t-to b-b-be there?’

Oh my goodness, a stutterpoem! There had once been a Zamonian literary movement - Gagaism, as it styled itself - that not only sanctioned speech defects but positively cultivated them. They really weren’t a special field of mine.

‘The s-s-sea, the s-s-sea, it

w-w-washed it up,

and th-th-there it l-l-lay

qu-qu-quite c-c-comfortably.’

w-w-washed it up,

and th-th-there it l-l-lay

qu-qu-quite c-c-comfortably.’

Wow! Orkle Thunk used to stutter and so did Dorian Borsh. The Waterhead Twins had stuttered whole duets together. There were even stutterpoems written by non-stutterers eager to climb on the Gagaist bandwagon.

‘Then al-l-long c-came a f-f-f

a f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f

f-f-fisherm-m-man f-f-fishing, f-f-f-fishing

f-f-for f-f-fresh f-f-fish.

He t-t-took it aw-w-way, aw-w-way,

aw-w-way, he t-t-took it aw-w-way.’

a f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f-f

f-f-fisherm-m-man f-f-fishing, f-f-f-fishing

f-f-for f-f-fresh f-f-fish.

He t-t-took it aw-w-way, aw-w-way,

aw-w-way, he t-t-took it aw-w-way.’

T. T. Kreischwurst, whose pseudonym was as asinine as his poetry, had written more stutterpoems than anyone else, but this one might just as easily be by Pankard Murch or Dongo Ghorkhunter. I would have to fall back on guesswork.

‘The r-r-rock n-n-now l-l-lies there

b-b-bereft of its s-s-skeletal f-f-fish

in the m-m-midst of the w-w-wide ocean,

l-l-looking t-t-terribly b-b-bare.’

b-b-bereft of its s-s-skeletal f-f-fish

in the m-m-midst of the w-w-wide ocean,

l-l-looking t-t-terribly b-b-bare.’

The Bookling bowed. At least he’d finished the confounded poem. Gee . . . No, I really didn’t know who’d written that embarrassing drivel, so I simply settled on the most popular stutterpoet of all.

‘You’re T. T. Kreischwurst!’ I said firmly.

‘Y-y-y-y-yes!’ the Bookling replied. ‘That was entitled “A L-l-l-l-little P-p-p-poem for B-b-b-b-big S-s-s-stuttuttuttutterers”.’

Applause and laughter. Phew! I’d made it again, albeit only by a whisker.

‘Next!’ Al called.

More candidates presented themselves in quick succession. Ydro Blorn, Rashid el Clarebeau, Melvin Hermalle and the rest - I guessed them all, one after another. Not for the first time since my arrival in the catacombs, I gave thanks to my authorial godfather for the extensive knowledge of Zamonian literature he’d drummed into me in my boyhood.

A Bookling the colour of a dark-brown calfskin cover stepped forward and declaimed,

‘Away! Old Lindworm Castle, fare thee well!

In freedom will I roam across the plain.

Henceforward all I do shall only serve

to win me the renown I hope to gain.’

In freedom will I roam across the plain.

Henceforward all I do shall only serve

to win me the renown I hope to gain.’

Aha, Lindwormian verse! Couldn’t he have made it a bit easier for me? Although I couldn’t identify the poem immediately, I naturally knew every word that had ever been written in the castle.

‘Renown! Let that sweet recompense be mine!

May all my dreams of eminence come true,

and may my lonely tombstone bear this line:

“A poet for the many and the few!” ’

May all my dreams of eminence come true,

and may my lonely tombstone bear this line:

“A poet for the many and the few!” ’

Just a minute! I

knew

this poet - he had recited these stanzas to me himself on some occasion. Of course! They came from Ovidios Versewhetter’s farewell poem on leaving Lindworm Castle. He had recited it to the entire Lindworm community in the belief that he was destined to become a celebrated literary figure in Bookholm. I never dreamed that the next time I saw him he would be languishing in one of the pits in the Graveyard of Forgotten Writers.

knew

this poet - he had recited these stanzas to me himself on some occasion. Of course! They came from Ovidios Versewhetter’s farewell poem on leaving Lindworm Castle. He had recited it to the entire Lindworm community in the belief that he was destined to become a celebrated literary figure in Bookholm. I never dreamed that the next time I saw him he would be languishing in one of the pits in the Graveyard of Forgotten Writers.

‘Bookholm, of dreaming books thou city vast,

abode of wealthy poets, I with thee

a bond intend to forge that long will last.

To this may Destiny my witness be!’

abode of wealthy poets, I with thee

a bond intend to forge that long will last.

To this may Destiny my witness be!’

There were another seventy-seven stanzas, all of which extolled the joys of a poet’s emancipated existence and the fruits of fame that were bound to be awaiting the youthful Lindworm in Bookholm, but I decided to give myself, the Bookling and his confrères a break, so I said, ‘You’re Ovidios Versewhetter.’

Other books

Lost and Sound by Viola Grace

Little Criminals by Gene Kerrigan

Blood Lies by Daniel Kalla

The Execution of Noa P. Singleton by Elizabeth L. Silver

In the Midst of Death by Lawrence Block

Titanborn by Rhett C. Bruno

Beauty in Disguise by Mary Moore

Be Not Afraid by Cecilia Galante

Malice in Wonderland Prequel by Lotus Rose

Wolf's Bane by D. H. Cameron