The City of Dreaming Books (16 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

‘Yes, this building is an architectural gem. One doesn’t see that at first glance,’ said a deep voice. I was jolted out of my reverie.

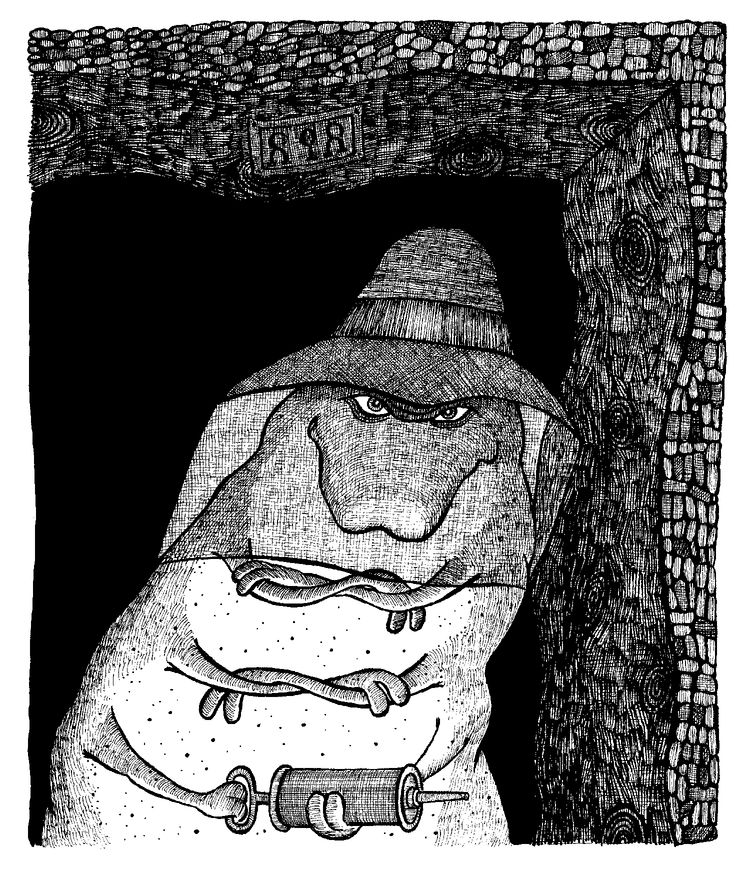

The door had opened without a sound, and leaning against the jamb was a Shark Grub. Although I had already seen a few representatives of that life form in Bookholm, this one was an exceptionally impressive specimen. The maggotlike torso looked grotesque with its fourteen skimpy little arms, and the neckless head was equipped with a set of shark’s teeth. The peculiarity of the creature’s appearance was not diminished by the fact that it was wearing a bee-keeper’s hat and veil and carrying a smoke gun.

‘Smyke’s the name, Pfistomel Smyke. Are you interested in early Bookholmian architecture?’

‘Not really,’ I admitted, somewhat bemusedly groping in my pocket for the business card the Hoggling had given me. ‘I got your address from Claudio Harpstick.’

‘Ah, dear old Claudio! You want to buy some books?’

‘Not that either, to be honest. I own a manuscript which—’

‘You want an expert opinion?’

‘Precisely.’

‘Wonderful! This is a welcome distraction. I was just cleaning my beehive out of sheer boredom. Do come in.’ Pfistomel Smyke retreated into the house and I followed, bowing politely.

‘Optimus Yarnspinner.’

‘Delighted to make your acquaintance. You’re from Lindworm Castle, aren’t you? I’m a great admirer of Lindwormian literature. Please follow me to the laboratory.’

Smyke undulated ahead of me down a short, dark passage.

‘Don’t let my hat and veil mislead you,’ he went on chattily, ‘I’m not a genuine bee-keeper, it’s just a hobby. When the bees stop producing I roast them and bottle them in honey. Do you think that’s heartless of me?’

‘No,’ I replied, running my tongue over my gums. The spot was still slightly inflamed.

‘It’s ridiculous, of course, going to all that trouble for one jar of honey in springtime. I only wear the hat because I think it’s chic.’ Smyke emitted a guttural laugh.

At the end of the passage was a bead curtain composed of lead type strung like beads on lengths of thin cord. Smyke parted it with his massive body and I followed him inside.

For the third time that day I entered another world. The first had been the Uggly’s dusty, airless bookshop, the second the sinister, historic heart of Bookholm. I was now admitted to a world of letters, a room completely given over to writing and its exploration. Hexagonal in shape, it had a ceiling that tapered to a point. The large window was obscured by red velvet curtains. The other five walls were lined with shelves on which reposed stacks of paper in a wide variety of formats and colours; retorts, flasks, alembics and vessels of all kinds containing liquids and powders; hundreds of goose quills neatly arrayed in small wooden racks; an assortment of metal-nibbed pens in little mother-of-pearl boxes; inks of every conceivable colour including black, blue, red, green, violet, yellow, brown and even gold and silver; rubber stamps and ink pads, sealing wax, magnifying glasses of various sizes, and microscopes and chemical apparatus of a kind I’d never seen before. All these things were bathed in the mellow, fitful light of flickering candles standing here and there on the shelves.

‘I call this my typographical laboratory,’ Smyke said with a touch of pride. ‘I conduct research into words.’

What surprised me most of all was the room’s size. The building had looked so small and skimpy from the street, I could hardly believe that this spacious laboratory fitted inside it. My respect for Bookholm’s ancient architecture increased by leaps and bounds as I strove to memorise as many details of these remarkable premises as I could.

There was writing everywhere. The velvet curtains over the window were printed with the Zamonian alphabet. Hanging between the bookcases were opticians’ charts in various typefaces and framed diplomas and slates inscribed with jottings in chalk, and pinned to the wall were tiny memos. A huge, freestanding lectern was cluttered with manuscripts, inkwells and magnifying glasses. Printer’s type of all sizes, either of wood or cast in lead, lay around on small tables beside bottles of printer’s ink, each of which was labelled - like a vintage wine - with its year and place of origin. Suspended from the ceiling were strings in various forms of quipu, or knot-writing, from which dangled small plaster tablets engraved with hieroglyphs. Standing here and there were strange mechanical contraptions whose purpose utterly defeated me. The floor was tiled with slabs of grey marble skilfully engraved with various alphabets: Druidical Runic, Ugglian Gothic, Old Atlantean, Palaeo-Zamonian and so on.

In the middle of the floor was a large closed trapdoor (the entrance to the catacombs?) and standing in a corner was a small crate filled with ancient tomes - the only books I had so far seen on the premises. Hardly a lavish display for an antiquarian bookshop. Was there a library next door?

‘I also have a small kitchen and a bedroom, but I spend most of my time in here,’ said Smyke, as if he had read my thoughts. No library? So where were his books?

It was only then that I noticed the shelf with the Leyden Manikins on it. Six of the little artificial creatures were romping around in their jars and tapping on the glass.

5

5

‘I’m using those Manikins to test the acoustic quality of various types of literature,’ Smyke explained. ‘I read them poetry and prose. They don’t understand a word, of course, but they’re extremely sensitive to intonation. Bad verse makes them double up as if they’re in pain, good verse starts them singing. They recognise a sad piece of writing by its sound and burst into tears.’

We paused in front of one of the bizarre machines, a wooden sphere resembling a terrestrial globe but engraved with letters of the Zamonian alphabet instead of a map. It could evidently be rotated by depressing a pedal.

‘A novel-writing machine,’ Smyke said with a laugh. ‘An ancient device once believed to be capable of producing literature by mechanical means - a typical example of Bookemistic idiocy. The sphere is filled with syllables cast in lead. When you operate the pedal they fall out and form a row. Naturally, all they ever produce is sentences like “Pilgeon sulfriger fonzo na tuta halubraz” or something similar. The results are worse than the phonetic verse of the Zamonian Gagaists! I’ve a soft spot for useless junk of this kind. That’s a Bookemistic inspiration battery over there, and that’s an idea refrigerator.’

Smyke pointed to another two grotesque contraptions.

‘If those things were regarded as technologically advanced, it must have been a very unsophisticated age. All those legends about sinister rituals and sacrifices are utter rubbish. The Bookemists were like children playing with type and printer’s ink. When I compare the products of our modern literary industry. . .’ Smyke cast his eyes up at the ceiling.

I nodded in agreement.

‘If you ask me,’ he said, ‘I’d sooner be alive today than in the Zamonian Dark Ages.’

‘Except that there weren’t any corrupt reviewers in those days,’ I said.

‘True!’ Smyke exclaimed. ‘I see we speak the same language.’

I pointed to the trapdoor.

‘Is that . . . ?’ I asked.

‘Yes, it is!’ Smyke replied. ‘My own private entrance to the catacombs of Bookholm - my stairway to the underworld. Wheee!’ He waved all fourteen of his little arms at once.

‘Is that where Regenschein . . . ?’

‘Correct.’ Smyke cut my hesitant question short. ‘This is where Colophonius Regenschein embarked on his quest for the Shadow King.’ He looked grave. ‘I still cherish the hope that he’ll return some day, even after five years.’ He sighed.

‘I’ve read his book,’ I said. ‘Since then I’ve been wondering where fact ends and fiction begins.’

An impressive change came over Smyke’s physique. Previously so flabby and vulnerable-looking, his maggotlike body tensed and grew taller. His expression became stern and piercing, and he clenched his numerous fists.

‘Colophonius Regenschein’s credibility is beyond dispute!’ he thundered at me, so loudly that he set the retorts on the shelves around us jingling. ‘He was a hero - a genuine hero and adventurer! He had no need to fabricate his adventures. He underwent them all in person and paid a heavy price.’

The Leyden Manikins trembled at his tone of voice and some of them burst into tears. I recoiled, intimidated by his sudden transformation. Noticing this, he promptly reverted to his former manner and subsided, both physically and vocally.

‘Forgive me,’ he said, every inch the literary scholar, ‘but this is still a very painful topic from my point of view. Colophonius Regenschein was a personal friend.’

I searched for something to say that would enable me to change the subject discreetly.

‘Do you believe in the existence of the Shadow King?’ I asked.

Smyke debated this for a moment. ‘That’s not a valid question,’ he said quietly. ‘No one who has lived in Bookholm for any length of time seriously doubts his existence. I myself have often heard him howling on windless nights. What interests me far more is another question: is he good or evil? Regenschein believed in his essential benevolence. Others assert that the Shadow King killed him.’

‘Which view do you take?’

‘A million dangers exist down there and any one of them could be responsible for his disappearance. They include Spinxxxxes that can grow to the size of horses, Harpyrs, Fearsome Booklings, vengeful Bookhunters - merciless creatures of all kinds. Why does it have to be the Shadow King who’s responsible for Regenschein’s disappearance? One could speculate on the matter ad infinitum.’

‘Do you know how the Fearsome Booklings got their name?’ I asked. ‘Are they really so fearsome?’

‘The Bookhunters called them that because they don’t shrink from devouring even the most valuable books. They’re reputed to feed on them when there’s no live prey available.’ Smyke chuckled. ‘To Bookhunters, devouring a valuable book is far more reprehensible than killing a living creature.’

‘Bookhunters seem to live by rules of their own.’

‘They’re dangerous, so for goodness’ sake beware of them! I occasionally have dealings with them for professional purposes, but I try to limit those contacts as far as possible. Every encounter with a Bookhunter leaves one feeling reborn. Why? Because one has survived!’

‘Shall we get down to business?’ I asked.

Smyke grinned. ‘You have a job for me? Would you care for a cup of tea first? A slice of bee-bread, perhaps?’

‘No thank you!’ I said hastily. ‘I’ve no wish to presume on your hospitality. I’m looking for the author of a manuscript. It must be somewhere here . . .’ I felt in my cloak but couldn’t find it at once. I had stuffed it into a pocket at random after my dramatic visit to the Uggly’s bookshop.

‘Right, let’s take a look,’ said Smyke, reaching for the manuscript when I finally produced it. He screwed a thick-lensed monocle into his right eye and unfolded the sheaf of paper.

‘Hm . . . High quality Grailsundian wove,’ he muttered. ‘Timberlake Paper Mills, 200 grammes. Unevenly trimmed, probably by an obsolete Threadcutter guillotine dating from the century before last. Overacidified.’

‘I know all that,’ I said impatiently. ‘It’s the text that interests me.’

I couldn’t wait to see what his reaction would be. If he knew anything at all about literature, he would be bound to display some emotion.

Pfistomel Smyke raised the manuscript until it was within range of his monocle. Even as he read the first sentence, his flabby body seemed to be transfixed by an invisible shaft of lightning. He reared up, trembling, and wavelets of emotion rippled across his masses of adipose tissue. He emitted a sound of which Shark Grubs alone are capable: a high-pitched whistle superimposed on a dull, booming note. Then he drew a deep breath and read on in silence for a while. All at once he gave a roar - of laughter. It was a prolonged paroxysm of mirth that made his torso wobble to and fro like a toy balloon filled with water. He quietened, then squeaked and gasped and giggled inanely. His growls of approbation alternated with phases of mute emotional turmoil.

I had to smile. Sure enough, he was displaying the whole range of emotions this same short story had evoked in me and Kibitzer. The corpulent creature not only knew something about literature but possessed a sense of humour as well.

Eventually he lapsed into dull, brooding silence. As far as he was concerned, I didn’t exist. His eyes glazed over and he remained motionless for several minutes. At last he lowered the manuscript and seemed to emerge from a profound trance.

‘My goodness,’ he said, gazing at me with tears in his eyes, ‘it’s truly sensational. The work of a genius.’

‘Well,’ I asked eagerly, ‘do you know the author? Can you at least point me in the right direction?’

‘Not so fast, my friend.’ Smyke smiled as he re-examined the manuscript, this time with a magnifying glass. ‘First I have to conduct a syllabic analysis and draw up a graphological parallelogram. Stylistic mensuration will be necessary, and I must work out the ratio of metaphors to the number of characters, calligraphically calibrating the text with my alphabetic microscope. Next will come an acoustic test with the Leyden Manikins and an analysis of the cutaneous scales adhering to the paper - the full programme, in other words. That will take, let’s see . . . the whole night at least. If you leave the manuscript with me now I shall be able to tell you more by noon tomorrow. Probably not the author’s name, but one or two things about him: whether he’s right- or left-handed, how old he was at the time of writing, what part of Zamonia he comes from, his weight, his personal traits and temperament, the authors that influenced him, the ink he uses, where it comes from and so on. I’ll be able to ascertain his name if he has become a well-known author since writing this, but that will take longer. I should have to do some research in the manuscript library. Will you be staying in Bookholm for a little while?’

Other books

Her 24-Hour Protector by Loreth Anne White

The Bachelor's Bargain by Catherine Palmer

The Blue Hackle by Lillian Stewart Carl

The Hidden Diary of Marie Antoinette by Carolly Erickson

Wish by Nadia Scrieva

The Return of Buddy Bush by Shelia P. Moses

Aaron: Mating Fever (Rocked by the Bear Book 4) by V. Vaughn

Dark Chocolate Murder by West, Anisa Claire

Bradley Wiggins by John Deering

The Man Behind the Iron Mask by John Noone