The City of Dreaming Books (19 page)

Read The City of Dreaming Books Online

Authors: Walter Moers

All this my mind’s eye saw enacted in images as clear as crystal: Pellogg staggered through the grounds of his palace, bleeding from dozens of tuning-fork wounds, and ended by tumbling into a goldfish pond whose waters turned pink. The trombophone music swelled to an almost unbearable cacophony and from the despot’s corpse my gaze once more travelled upwards to the sky above, where chaos raged, planets and stars danced wildly to the blare of the orchestra, and the entire universe became distorted into a maelstrom of stars and planets that went whirling off into a black void. At that moment the trombophone music abruptly ceased.

My eyes shot open. I was seated on the very edge of my chair, panting and bathed in sweat despite the chill evening air.

All the concertgoers were talking excitedly. I saw the Uggly dabbing Kibitzer’s brow.

‘That was simply magnificent,’ gasped the dwarf beside me. ‘I’ve heard it dozens of times and it still works. No, what am I saying? It gets better and better!’

‘It becomes stronger every time, the sensation of being whirled along in a vortex of stars,’ someone behind me exclaimed. ‘For one glorious moment I thought I was a star myself!’

It was incredible: we had all shared the same vision. These concertgoers were obviously regular attenders who heard the same music, saw the same images and dreamt the same stories again and again. Had I not been there myself, I would never have believed such a form of artistic mediation possible. Then, if not before, I ceased to regret having come and resolved to thank Pfistomel Smyke in person the next morning.

The orchestra struck up once more. The notes sounded flutelike, almost nasal, and I readily shut my eyes. I saw granite castles silhouetted against grey, overcast skies; pennants fluttering in the wind above mounds of slain warriors clad in blood-encrusted armour; quarrelsome ravens perched on gibbets with corpses dangling from them; charred skeletons on smouldering pyres. I had evidently been transported to the Zamonian Middle Ages.

It was a mystery to me how the musicians managed to coax such notes from their trombophones. They sounded like the primitive wind and string instruments of those days: squawks and monotonous wails, discordant caterwauling and the mournful drone of bagpipes. All at once I was looking out across a delightful landscape, an endless expanse of vineyards under a radiant summer sky, and in their midst a mountain that resembled the cloven skull of a giant filled with dark water.

This could only be Grapefields, Zamonia’s largest wine-growing area, and the mountain was the Gargyllian Bollogg’s Skull. Once again I knew something without knowing how I had learnt it. This was the story of Ilfo Guzzard and his legendary

Comet Wine

. Until then I had known it only through the medium of Inka Almira Rierre’s poem ‘Comet Wine’, but now my brain became filled with all the details of that gruesome medieval drama.

Comet Wine

. Until then I had known it only through the medium of Inka Almira Rierre’s poem ‘Comet Wine’, but now my brain became filled with all the details of that gruesome medieval drama.

Once every thousand years the Lindenhoop Comet travels through our solar system and comes so close to our planet that its light transforms a whole summer into one long, brilliantly illuminated day.

Ilfo Guzzard, the most influential wine grower of the Zamonian Middle Ages, owner of numerous vineyards in Grapefields and an amateur alchemist, was convinced that vines planted shortly before this nightless summer were bound to yield a wine more mature than any that had ever been bottled. In short, he aimed to produce a Comet Wine.

The comet drew nearer, the longest of all days dawned, and the heat of the sun and the light from that celestial body lent Ilfo’s vines a quality surpassing all his expectations. They grew far more quickly and their grapes attained the size of watermelons - the pickers had to pluck them with both hands, one at a time, and carry them, groaning, to the wine press. Their juice was viscous and heavy, full-bodied and delicious, and the wine they yielded was the best of all time. And Ilfo Guzzard possessed a thousand barrels of it! One day he summoned all his employees - vine pruners and grape merchants, planters and pickers and coopers - to a meeting in his courtyard. Then the gates were shut. Taking an axe, Ilfo proceeded to chop holes in every last barrel. His employees thought he had lost his wits and tried to restrain him, but Ilfo would not be restrained. He didn’t rest until the last barrel was smashed, the last drop had seeped into the ground and the whole courtyard was awash with Comet Wine.

Finally, Ilfo held up a bottle. ‘This, my friends,’ he announced triumphantly, ‘is the last remaining bottle of Comet Wine, the finest and most delicious, rarest and most valuable wine in Zamonia. I’ve no need to house and tend any more bottles and barrels, no need to pay any more taxes and wages, nor will I need to go in fear of the Zamonian customs and excise authorities. All I shall need is this one bottle of wine, which is now worth a fortune, and all I shall have to do is watch it appreciate in value every day. I’m retiring.’

‘What about

us

? What’s to become of

us

?’ asked one of his minions.

us

? What’s to become of

us

?’ asked one of his minions.

Ilfo Guzzard eyed him sympathetically.

‘You?’ he said. ‘What’s to become of you? You’ll be unemployed, of course. I’m firing you all as of now.’

Not until that moment, as he stood there in the midst of hundreds of unemployed workers with history’s most valuable bottle of wine in his hand, did it dawn on Ilfo Guzzard that it might have been wiser to give them notice of dismissal in writing. Their eyes were blazing with murderous intent - and also with a desire to own that priceless bottle of wine. They slowly and steadily converged on him.

‘Very well,’ thought Ilfo, who may have been a rotten employer but was certainly no coward, ‘if I must die, at least I’ll die drunk. No one’s going to own my Comet Wine but me.’

He knocked the top off the bottle and drained it at a gulp. Then he was lynched by his workers. But he had underestimated the greed his speech had kindled in them. Having carried his corpse to the biggest wine press on the estate, they threw him into it and juiced him. They squeezed Ilfo until the last drop of Comet Wine had been extracted from his corpse, along with his blood, and bottled the frightful liquid in a jeroboam. It was now indeed the rarest and most valuable wine in Zamonia.

But the truly horrific story of Comet Wine was only just beginning, because it brought its successive owners nothing but the worst of bad luck.

Ilfo Guzzard’s workers were executed for his murder, the next owner of the bottle was struck by a meteor and the one after that devoured by ants while asleep. Wherever the bottle went, murder and mayhem, war and madness soon followed. Many people believed that Comet Wine could restore the dead to life, so it was greatly coveted in alchemistic circles. The jeroboam passed from hand to hand, leaving a trail of bloodshed throughout Zamonia, until one day the trail suddenly ended and the receptacle containing Ilfo Guzzard’s wine and blood seemed to vanish from the face of the earth.

The musical epilogue was a quivering tremolo that embodied the full horror of the story. Absolute silence followed.

I awoke from a state akin to hypnosis. The concertgoers around me were murmuring excitedly, the trombophonists bottle-brushing their mouthpieces with a satisfied air.

‘That was new,’ exclaimed the dwarf beside me. ‘The Comet Wine piece wasn’t on last week’s programme.’

Aha, so they didn’t always perform the same pieces. I felt privileged to have been present at a kind of première and closer in spirit to the admirers of Murkholmian trombophone music. By now, ten Midgard Serpents wouldn’t have dragged me from my seat. I was eager for more of the same.

The murmurs died away, the musicians raised their instruments once more.

‘Next comes some gruesic, I reckon,’ the dwarf said with obvious pleasure. ‘It’ll go well with that gory tale of the Comet Wine.’

‘What’s gruesic?’ I enquired.

‘Wait and see,’ the dwarf replied mysteriously. ‘Now things will get really weird.’ He broke off in mid chuckle. ‘Hey, didn’t you bring a shawl? You’ll catch your death.’

I couldn’t have cared less. I was willing to make any sacrifice for the sake of some more trombophone music.

Several of the Murkholmers projected shimmering notes high into the night sky while others blew discreetly in the bass register. I shut my eyes again, but this time I saw no overwhelming panorama. Instead, my head became filled with a profound understanding of the Dervish music of Late Medieval Zamonia - of which I’d known absolutely nothing until then.

Dervish music, I suddenly knew for certain, was based on a heptametrical scale whose intervals were measured in units called

shrooti.

Two

shrooti

equalled a semitone, four

shrooti

a whole tone and twenty-two

shrooti

an octave. That an interval should have taken its name from a musician was an honour unique in Zamonian musical history. Octavius Shrooti, the legendary Dervish composer of the Late Middle Ages, had evolved a gruesome form of music, or ‘gruesic’, capable of being blended with any composition. It was based on sounds calculated to inspire dread: dogs howling in the night, creaking hinges, the cry of a screech owl, anonymous voices whispering in the dark, rumbles from beneath the cellar stairs, malevolent titters in the attic, women weeping on a blasted heath, screams from a lunatic asylum, fingernails scratching slate - whatever made a person’s hair stand on end and could be imitated by musical instruments. Shrooti blended this gruesic with popular contemporary music in an extraordinarily successful manner. In his day people went to concerts mainly for the purpose of being scared out of their wits. Ovations took the form of cries of horror, mass fainting fits equated to requests for encores, and when panic-stricken members of the public jostled their way to the exit, screaming, the concert had been a complete success. Coiffeurs styled their clients’ hair so that it stood on end, chewed fingernails were considered chic, and concertgoers who chanced to meet in the street would greet each other with an affected ‘Eeek!’ and throw up their hands in simulated horror. A whole series of musical instruments originated at this time, among them the gallows harp, the devil’s bagpipes, the trembolo, the ten-valved macabrophone, the death saw, the dungeonica and the throttleflute. Not for nothing was Octavius Shrooti’s heyday known as the

Gruesome Period.

shrooti.

Two

shrooti

equalled a semitone, four

shrooti

a whole tone and twenty-two

shrooti

an octave. That an interval should have taken its name from a musician was an honour unique in Zamonian musical history. Octavius Shrooti, the legendary Dervish composer of the Late Middle Ages, had evolved a gruesome form of music, or ‘gruesic’, capable of being blended with any composition. It was based on sounds calculated to inspire dread: dogs howling in the night, creaking hinges, the cry of a screech owl, anonymous voices whispering in the dark, rumbles from beneath the cellar stairs, malevolent titters in the attic, women weeping on a blasted heath, screams from a lunatic asylum, fingernails scratching slate - whatever made a person’s hair stand on end and could be imitated by musical instruments. Shrooti blended this gruesic with popular contemporary music in an extraordinarily successful manner. In his day people went to concerts mainly for the purpose of being scared out of their wits. Ovations took the form of cries of horror, mass fainting fits equated to requests for encores, and when panic-stricken members of the public jostled their way to the exit, screaming, the concert had been a complete success. Coiffeurs styled their clients’ hair so that it stood on end, chewed fingernails were considered chic, and concertgoers who chanced to meet in the street would greet each other with an affected ‘Eeek!’ and throw up their hands in simulated horror. A whole series of musical instruments originated at this time, among them the gallows harp, the devil’s bagpipes, the trembolo, the ten-valved macabrophone, the death saw, the dungeonica and the throttleflute. Not for nothing was Octavius Shrooti’s heyday known as the

Gruesome Period.

The music died away and I opened my eyes. The dwarf beside me grinned.

‘Now you know: that was gruesic. But this is when it really hots up. Be prepared for anything!’ He sat back and closed his eyes with a sigh of anticipation.

Four trombophonists produced a chorus of howls that put me in mind of bloodhounds drowning in a castle moat. Two more imitated the bleating laughter with which Mountain Demons unleash avalanches. The fattest trombophonist seated in the middle of the orchestra persuaded his instrument to emit a despairing sigh like the final exhalation of someone being strangled by a garrotte. I also seemed to hear the pitiful cries of people buried alive and the screams of Ugglies burning to death.

Somewhat perturbed, I shut my eyes again. What horrific scenes would this music summon up in my mind? What terrible story would it recount?

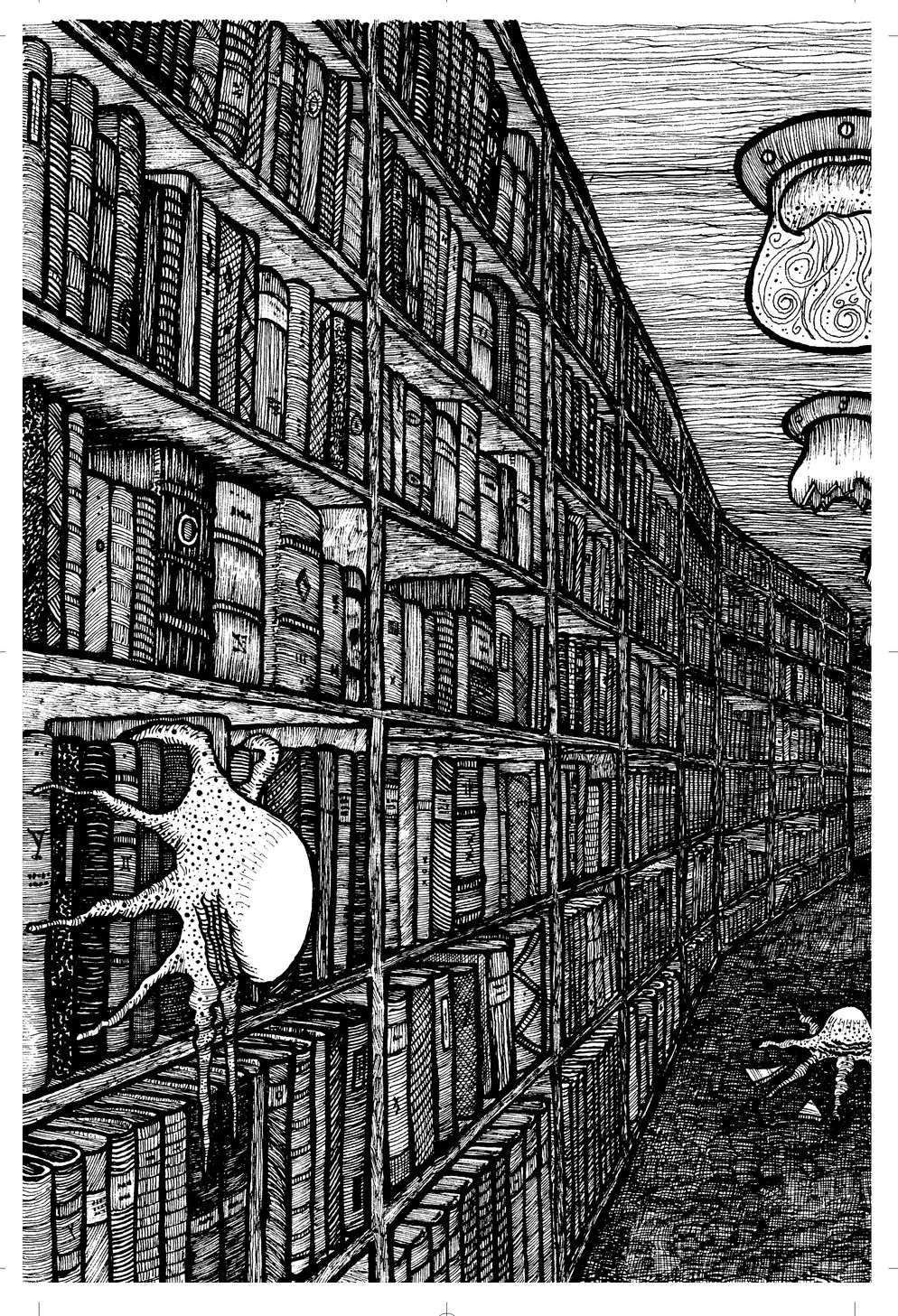

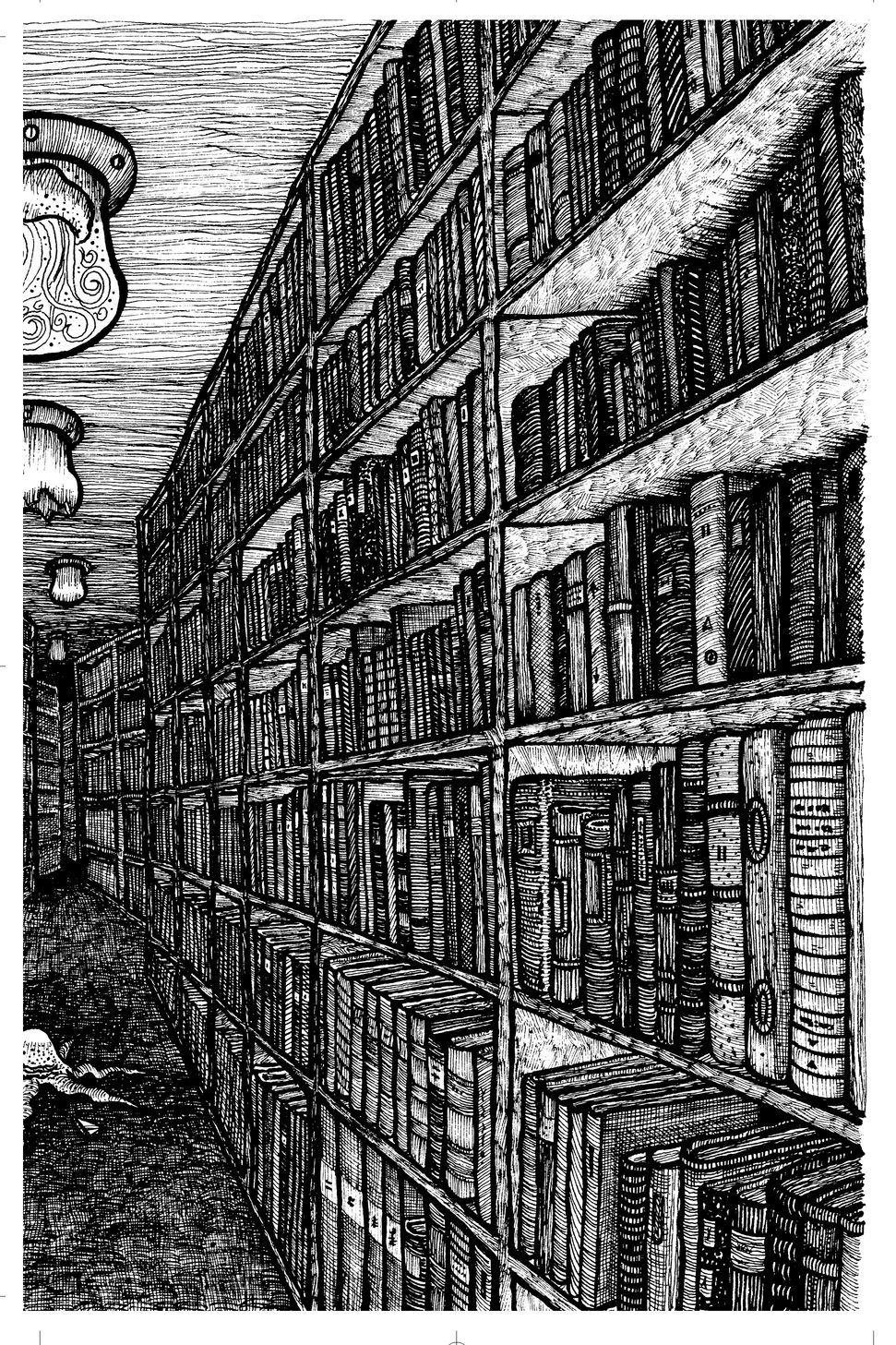

At first I saw nothing but books. I was looking down an endless passage lined with shelves and old books. Surely nothing untoward could happen in an antiquarian bookshop? I studied the backs of the books more closely. Heavens, they weren’t just old, they were

very

old - so ancient, in fact, that I couldn’t decipher the titles. Several curious ceiling lights dispensed a ghostly, pulsating glow. Something was moving inside them. Were these the jellyfish lamps described by Regenschein?

very

old - so ancient, in fact, that I couldn’t decipher the titles. Several curious ceiling lights dispensed a ghostly, pulsating glow. Something was moving inside them. Were these the jellyfish lamps described by Regenschein?

At last I caught on: these were the catacombs of Bookholm - the labyrinth beneath the city, and I was in the midst of it! How fantastic, a subterranean journey into that mysterious, perilous world devoid of any personal risk! I need only listen to the music and devote myself to the scenes as they unfolded.

I opened my eyes briefly and closed them again, then repeated the procedure several times in succession. Sure enough, I could effortlessly alternate between the Municipal Gardens and the catacombs. Eyes open: Municipal Gardens. Eyes shut: catacombs.

Other books

Gideon's Gift by Karen Kingsbury

The Houseparty by Anne Stuart

He's After Me by Higgins, Chris

Las suplicantes by Esquilo

Miles de Millones by Carl Sagan

The Vaults by Toby Ball

Severed Threads by Kaylin McFarren

Rojan Dizon 02 - Before the Fall by Francis Knight

The Last Garrison (Dungeons & Dragons Novel) by Beard, Matthew

A Cozy Country Christmas Anthology by Melange Books, LLC