The Broken Lands (48 page)

Authors: Kate Milford

Days before, Walter Mapp had said, “Nothing feels like something till after everything's over.” It seemed to Sam that he ought to feel it nowâthat he ought to feel joy, pride, relief . . .

something

. He was waking up in a changed world, wasn't he?

Tesserian leaned on his elbows. “After a parade,” he said softly, “when all that's left is confetti in the streets, everyone goes back to work. Somebody unhitches the horses, somebody sweeps up, and little by little, garbage starts to pile up in its usual places. Until the next parade, when everything's made shiny again for another few hours of celebration.”

“We did something way more important than a parade,” Sam protested.

“Sure, sure, you saved the world.” Tesserian waved an arm. “And this is the world you saved. Did you expect it to be different, suddenly? Did you expect it to be grateful?”

“No, it isn't that.” And it wasn'tânot quiteâbut it was, somehow,

close

.

“You expected that

you

would be different,” Tesserian suggested.

“Yes!” That was it. That was

exactly

it.

The sharper nodded. “Well, I wish I had some advice for you. The roamer in me says that means you need a change of scene. But then I feel bound to tell you that it's best not to go looking for yourself out there on the roads. The view changes, but there's no guarantee

you

will.” He scratched his head. “Nope, can't really give you advice. But I do want to give you something else.”

He reached under the table, produced his gambling kit, and took from it the Santine deck. “This is yours.”

“Mine?” Sam reached out to take it. The overlapping circles on the back of the top card shimmered in the sunlight. “Really? Why?”

“Are you kidding?” Tesserian burst into laughter. “You won by making up a new rule during the game! You

earned

this. It's yours. That's the only way you come to own a Santine deck, you know. You have to win it.”

“Oh, I see,” Sam said, recalling the previous night's game. “That's why Walker was so shocked that I had it. You told him I won it from you.”

“Exactly. A little lie that turned out to be partly true in the end. You got it from me, and you got it because you beat Walker. And without cheating, too.” He grinned. “I hope you won't mind that I'm proud as Punch to have been your teacher for a couple hours.”

Sam reached across the table to shake Tesserian's hand. Then he touched the bruise still darkening his own cheekbone. “Next time you can teach me how to throw a punch like that.”

Tesserian laughed as he closed up his kit. “You bet.”

“Are you going to stick around Coney Island for a while?”

“Nah.” He looked up at the sun, then licked his index finger and held it up to test the wind. “Probably head out today. But thank you for sharing your spot. It's all yours again.”

“Thanks.” But even as he spoke, it occurred to Sam that he wasn't sure he wanted his spot back.

Tesserian watched him as if he knew exactly what Sam was thinking. Then he stood up, tucked his kit under his arm, and clapped Sam on the shoulder. “Never expect the world to make sense before breakfast, kid. I'll see you around.”

And with that, the sharper ambled across Culver Plaza toward the train tracks leading out of town. Sam watched him for a few minutes, running his fingers around the edge of the Santine deck. Then he pocketed it carefully and started walking again himself.

The Broken Land Hotel glowed peacefully in the early sun. Sam saw only one other person up and about as he wandered across the lawn that faced the water.

He waved. Susannah Asher waved back and strode to join him.

“Morning, Susannah. Couldn't sleep either?”

Susannah shook her head. “Too much to think about.” She gave him a doubtful smile. “Will you keep your post, now that the crisis is over? Have you given that any thought?”

Keeper of the conjunction

. All four of the new pillars would have to decide now whether or not to promise their lives to the keeping of the city.

“Sure, I gave it thought. Couldn't sleep last night for thinking about it.” He looked down at his fidgeting hands. “Susannah, it would be the greatest honorâ”

“But.” She smiled sadly.

“But . . .” He looked across the lawn to where the roofs of the Fata Morgana compound were just visible over the tops of the ornamental trees by the stable, and thought about Tesserian's words. “I just don't know if I can promise to stay. Not forever, anyway. I'm sorry.”

Susannah put a hand on his shoulder. “Don't apologize. That's a really, really good reason to say no.”

“Will you be able to find others? The right people to stand with you, if anybody else decides to decline?”

“Well, it works differently each time, but, I think . . .” She smiled slowly. “Yes. I'll find them, or they'll find me.” She kissed his cheek and squeezed his fingers. “Goodbye, Sam.”

Â

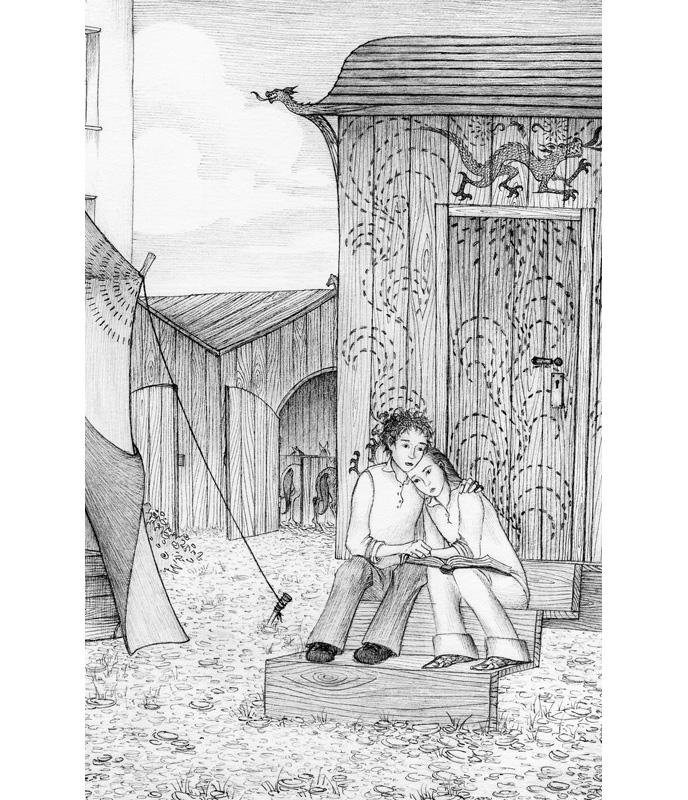

He found Jin awake, too, and sitting on the steps of the wagon with the green leather book on her lap. She looked up from it as his feet crunched across the gravel. “What is it with all of us?” she demanded. “Can't anyone sleep? Mr. Burns was up before the sun this morning, too.”

“Con's still snoring back home,” Sam told her. “Fell asleep with his clothes on and everything.” He sat beside her on the step. “No sign of your uncle?”

“No, but I don't think he's gone.” She raised her eyebrows, drawing his attention to the shiny red swath across her forehead. She'd washed off the residue of the

dan,

but there was still a mark standing out against her skin like a burn. “I have this strange idea that we'll find him right about when this heals up.”

Sam touched the mark gently. “Does it hurt?”

She shook her head. “I'm aware of it, but it isn't quite pain.”

He leaned in and kissed her temple. Jin closed her eyes. “When do you leave?” he asked.

“I don't know. Tomorrow, most likely. Whenever Uncle Liao's furnace is cool enough to move.” She sounded just as miserable as Sam felt.

He put an arm around her, and she scooted closer and rested her cheek on his shoulder. “You'll come back,” Sam said quietly. “Promise me you'll come back sometime.”

“Samâ”

“Oh, for pity's sake.” They sprang apart and Sam leaped to his feet as Mr. Burns approached across the gravel. “Stop looking like you just got caught robbing a bank. After what we've just been through?” The man snorted as he jogged up the steps. “For crying out loud, Jin, see if the kid wants to come with us. We'll be back this way in a couple months. We can bring him home then.”

Sam's jaw dropped. Jin's face went scarlet.

“I'm sure he doesn'tâ”

“And you wouldn't want

me

toâ”

“I meanâ”

“Obviouslyâ”

“Would you?”

Sam stopped stammering and looked at her. Jin sat wide-eyed and still as stone on the step.

“I would if you wanted me to,” he said simply.

She let out the breath she'd been holding. “Come with me, then.”

They looked at each other for a moment, Sam frozen mid-pace a yard or so away, Jin unmoving on the wagon stair.

He put an arm around her, and she scooted closer and rested her cheek on his shoulder.

He put an arm around her, and she scooted closer and rested her cheek on his shoulder.Â

Sam felt a giant smile break out across his face, so wide it made his jaw ache. “All right.”

Jin grinned back at him, and then she was careening into his arms, hugging him so tightly he could barely breathe. “Wait until you see,” she murmured. “There's so much out there I want to show you.”

“The country is wide and strange,” Sam said, remembering Ambrose's words. Now, however, the idea of the wide and strange country was wondrous, somehow. Magical, maybe. Something worth discovering and sharing.

“Just wait.” Jin sighed happily, her heart thudding against him and her eyes bright with thoughts of the world beyond the gravel lot. “Wait until you

see

.”

This is a made-up story, but a lot of it is true.

Brooklyn is real, and it's wonderful. The Brooklyn Bridge is one of the most beautiful things in the world, especially at sunset. People really did give their lives to build it; the first one was its architect, John Augustus Roebling, who died from complications arising from a crushed foot sustained while surveying the site just as the construction of his work of art was beginning. His thirty-two-year-old son, Colonel Washington Roebling, took over the job of chief engineer. By the time the bridge was completed, Washington had become gravely ill himself from caisson disease, and his amazing wife, Emily, worked with him to see the construction finished. Washington survived, but several men died of caisson disease during the building of the New York tower, just like Sam's father.

I did take a few liberties with what I wrote about the bridge. The incident with the snapped steel strand actually occurred in the summer of 1878, killing two people; there was also a separate incident of fraud in which one of the vendors substituted brittle, poor-quality wire for the good stuff the bridge engineers had inspected. I combined these two events to create the accident that injured Constantine. I also took some license on the timing of the cable spinning, which was just beginning in 1877, and the description and use of the buggy Jin employs to hang her message. The buggy was used later, to wrap the finished suspension cables. At earlier points in the construction, workers also used boatswain's chairs, which were basically plank swings that hung from the cables. What I've described Jin and Mapp using is a sort of hybrid of the buggy and the boatswain's chair.

Coney Island is real, of course, as are several of the places mentioned there: Norton's Point, West Brighton, Culver Plaza, and the East End, where, by the end of the nineteenth century, several huge hotels like the Broken Land would be built. The Broken Land Hotel itself, however, is invented. Mammon's Alley is invented as well, but it's based on a lane in West Brighton (called the Bowery, after the infamous street in Manhattan) that became notorious just a few years later. In the late nineteenth century, Coney Island really was a place where the incredibly rich vacationed less than five miles from where criminalsâlike Boss Tweed, for instanceâcame to hide in the neighborhood of Norton's Point after fleeing New York City. In between was West Brighton, where the working people spent their holidays and their hard-earned pennies and nickels. It's a truly fascinating spot that has been strange and wonderful throughout its history, and one of the hardest aspects of writing about it was having to ignore some of the astounding things that happened there just a few years or a few decades later.

Red Hook is also real, although these days there's an Ikea roughly where Basile Christophel's church would be. Columbia Heights is an actual place, too; during the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge, that's where Washington and Emily Roebling lived. Susannah Asher's tunnel is invented, but it's based on an abandoned tunnel from the 1840s that runs under Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn. To get into it, you have to climb down through a manhole in the middle of the street, then creep through a hole in a wall and down another ladder. Once you're there, it's just as I've described it, except that it ends in a wall rather than a hidden exit. There are all kinds of fascinating speculations about what lies on the other side of that wall, by the way.

Here are a few other curiosities I had a good time with in this book. Christophel's praxis is based in equal parts upon hoodoo conjury and an assortment of Linux computing and hacking processes. Ambrose Bierce was a real, and brilliant, writer of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He's best known for two kinds of horror stories: uncanny tales of strange occurrences, and tales inspired by his own experiences in the Civil War. Walter Map was a real writer tooâalthough his heyday was the twelfth century. I've chosen one of the less-common spellings of his last name for this story; it's usually spelled with just one

p

. The poets Jin and Liao read and quote from are real, and the

waidan

described in this book is a hodgepodge of Chinese alchemy, Taoism, and fireworking history. If you're interested, you can find an index of sources and further reading at my website,

www.clockworkfoundry.com

.

Another part of the story that's true is this: In 1877, the United States was in trouble. The Civil War had ended and Reconstruction was theoretically over, but the country hadn't healed yet. There was a contested presidential election, rampant unemployment, and strikes that descended into violence. There was mistrust between workers and corporations, between citizens and government, between rich and poorâthe kind of mistrust that often escalated past sharp words and into violence, too. It was a very low point in our past, and one that's often forgotten when American history of the nineteenth century is taught. And in a certain light, it all looks uncomfortably familiar.