The Broken Lands (19 page)

Authors: Kate Milford

If it had been another boy talking about his awful past in the tenements, Sam would've tossed an arm over the kid's shoulder or thumped him on the back, but it didn't seem like the right thing to do now. Also, he suspected that Jin might take a dim view of any fellow who put his hands on her uninvited for the second time in less than fifteen minutes.

“How did you get away?” he asked at last.

“There was a man who was a miner. He had an old . . . injury, and when he came to the house, he would talk, that's all. So I asked him about explosives. I pretended to be amazed by themâI was much younger, a little girl. He would bring firecrackers and squibs, little things he could set off in the courtyard without burning the place down. I asked questions, and little by little I learned, and then I started stealing the powder and fuses.”

The catherine wheel had gone out some time ago. Jin began removing more supplies from her explosives bag as she continued.

“Somewhere along the way I think he figured out what I was up to. I think he might even have brought certain things just so I could take them. Perhaps I could've told him, but I thought if I let him help me escape he might expect me to leave with him. Then, when I had saved up enough and thought I knew enough to try, I set the explosives off. I blew up half the house and left in the chaos.”

“You blew up the house to escape?” Sam didn't even try to keep the admiration out of his voice. “When you were eight?”

“I was nine by then.” But she smiled just a little as she corrected him. “Blowing it up wasn't hard. The hard bit was getting everyone out of the part I wanted to demolish.”

“Still.”

“I managed to hobble three blocks from the house before a wagon pulled up in front of me. It was Liao and Mr. Burns, of course.” Jin pulled a pair of jars from her bag, unscrewed the caps, and sifted the contents together in a metal pan. “They'd been passing through San Francisco, and they happened to have been close enough to see the explosion I'd set. Liao jumped down and chased after me and of course I couldn't run. He took one look at my hands and knew I'd been messing around with powders.”

She turned and held out one hand to Sam so that he could see. Her gloved fingers were touched with dark smudges of ash. Then she pulled off the gloves and held out her hand again. It bore the marks of old and still-healing burns: shiny skin on the knuckle of her index finger and the end of her thumb, and a scar near her wrist that stood out pinkish against the golden tone of the rest of her hand. She rose, set the pan a few feet from them, and poured a few drops of oil over the powder mixture. A sharp waft of cinnamon drifted up.

“I thought for certain they would take me to the police, but Uncle Liao said if I could do that with stolen firecrackers, I might be worth teaching. The explosion had particularly difficult-to-achieve shades of crimson and gold, you see. I had somehow managed to blow up my prison with flair. And that's how I got my names: Jin means âgold,' and my stage name, Xiaoming, was the name of an emperor's daughter from old myth. It means âshines in the night.'”

She shook the concoction gently, like a prospector panning for precious metals, and placed it carefully on a flat stretch of sand. “The first thing he did was cut the binding off. He said a proper fireworker has to be able to run if things go wrong. You can imagine I didn't argue. Of course, some of the damage was already done. We discovered we had to wrap them up again and allow my feet to adjust to looser and looser bindings, a bit at a time. We let my feet out like that, little by little. It took years before I could teach myself how to run again.”

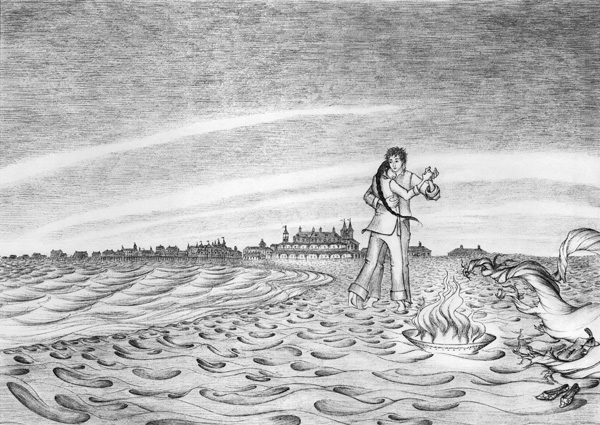

Jin lit the mixture in the pan with her pocket lighter, and it flared into a neat little blaze. “Instant bonfire,” Sam said with a smile.

Jin nodded and sat beside him again, arranging the cuffs of her trousers so they covered her shoes. She didn't say anything more.

The bonfire had a silvery tone to it, and the smell of cinnamon still hung in the air. Sam's chest was tight with a dull ache.

Somewhere across the lawns behind them, despite the horror that had just been discovered on the hotel grounds, an orchestra at the Broken Land was playing a waltz. The sound carried through the night as clearly as if they were only a few yards away from the bandstand.

“I know how this is going to sound,” Sam said at last, “and I'm sorry for it, but I think I'm right.” He took a deep breath. “I think you should take off your shoes.”

She glared at him. “I beg your pardon?”

He hadn't suggested she shuck off her clothes, but it wasn't all that far off. “I know this is an utterly inappropriate thing for me to say, but you should do it. Everyone should feel the sand between their toes when they can.”

For a long moment he watched her debate it, the glare firmly ensconced on her face all the while. In the end, though, the frown between her eyes faded. “All right.”

She reached down, fumbled under the wide cuffs of her cotton trousers, and produced a pair of embroidered red shoes with pointed toes, which she set neatly to one side.

Sam waited. “Well?”

“Well what?”

“How is it?”

She considered. “Very nice, actually.”

“You can't tell just from sitting there like that. Get up, walk around. And would you quit worrying?” he added as she shifted her weight awkwardly. “I didn't suggest it so I could try and sneak a look.”

She muttered something in Chinese, stood, squared her shoulders, and took a few steps. Despite what he'd just said, Sam wondered whether she would notice if he tried to catch a glimpse of the feet she was so worried about. It was dark, after all . . . but somehow, he managed to keep his eyes away from the ground.

“It's nice,” Jin said again, and this time her voice was softer. She walked farther. “Feels good, actually. You're right.”

Sam watched her circle back around the fire. He had begun to suspect that the awkward gait he'd noticed on Culver Plaza was something that she fell into when she, herself, felt awkward. She'd had it again when they'd crossed the hotel's atrium, but earlier, just after the fireworks when she'd been so happy, it was as if she'd forgotten all about her damaged feet, and her body had forgotten along with her. He watched for the awkwardness now, but her steps merely looked deliberate as she strode across the sand toward him again.

The faraway waltz drifted in the air, and the breeze made her clothes ripple and her hair catch brief glimmers of light from the fire. The ache in his chest was threatening to make him say something stupid. But then, he wondered, how would he feel if he didn't say anything at all? What was the worst that could happen?

So he said it. “Would you dance with me?”

Jin stopped walking. “I can't dance, Sam.” No wariness this time, and no coyness either. She spoke as if she thought she was saying something obvious.

“Because of the binding or because you never learned?”

“Both.”

“But you can run.”

“Yes, but it hurts. It always hurts.”

“Then I have another suggestion.” He got to his feet and held out his arms. “Trust me. Think how well the last one turned out.”

She looked at him for a long time. “I came out here with you, and we sat here in the dark, alone. I told you things I never tell anyone. I took off my shoes. I know how this must appear. You might be thinking . . . but please don't get the wrong idea. I couldn't bear it.”

The ache twisted. There it was, exactly what he'd been afraid of. What had she said earlier?

I want to know if you're going to mistake that for an invitation.

“I don't think that,” Sam protested. “You know I don't think that, don't you?”

“Then why are you here?” she asked wildly. “And you want to

dance?

White boys don't dance with girls who look like me.”

“That's only because there are about five girls in the country who look like you,” Sam retorted. “And because people are stupid.” He dropped his arms. “I don't know what to say to you. I'm not good at talking to people, not like this. But I know how to dance, and it makes me sad to see you sad. Please dance with me.”

She looked back at the fire, as if it had advice to offer. Then she nodded once and stepped closer.

Sam put an arm lightly around her waist. “You know what a waltz is?”

“That's the one that goes

one, two, three, one, two, three

?”

“That's the one. Now, about the part where it hurts your feet. Do you trust me?”

Jin gave him a wary glance. “Not remotely.”

Sam smiled. “I don't think that's true.”

And I hope I'm right about that

. “This is how we get around the pain.” He stepped closer still and tightened his arm, bringing her body right up against his and lifting her almost, but not quite, off her feet.

Jin's eyes snapped wide. “What are you doing?”

“Just reducing the weight you're putting on your feet, that's all.” Of course, that wasn't all. They were nose-to-nose now, and he could feel her heart hammering against his chest. “Put your hand back on my shoulder, like this. Ready? Andâ”

“Sam.”

“Yes?”

“If you put one finger out of line, I will kill you. You believe that?”

“Yes, actually, I do. Now, one . . . two . . . three . . .”

It didn't happen easily, but he managed to get them waltzing.

Somewhere on their second turn around the bonfire, the tension began to melt out of her. Not long after that, Sam realized the hand she'd rested on his shoulder had crept around his neck to hold on to him. She smelled like gunpowder and cinnamon, and he couldn't breathe in the scent deeply enough. He kept on counting steps, whispering numbers as the silver-and-red bonfire threw wild reflections into the eyes that looked past his shoulder into the night.

They danced until the faraway music faded, leaving them standing beside the fire, arms wrapped around each other. Jin had never looked up at him, had never met his eyes, but her head rested on his shoulder now. Sam turned just enough to see the plane of her face and felt her cheek against his chin.

They danced until the faraway music faded.

They danced until the faraway music faded.Â

“Jin . . .” he said quietly. “How are your feet?”

She smiled and spoke against his neck. “I feel as light as a spark.”

“Good,” he said. “That's all that matters.”

From somewhere in the dark, a barking explosion sounded, followed by a loud whining whistle. A shaft of white light shot heavenward and exploded into a shower of pink stars overhead.

Jin looked to the sky. “That's Uncle Liao's signal.”

“I'll take you back.”

She turned in his arms to watch the last of the pink sparks fall, and he watched her with his heart in his throat. Then she nodded once, slid out of his grasp, and returned to the driftwood and her rucksack. Sam stood awkwardly by the fire in its pan, unsure whether he ought to say something now or not.

Jin took her little knife from the bag and pulled the gloves back on. Then she stripped the darkened catherine wheel and returned to the fire just long enough to drown it in sand. While she slid her feet back into her shoes, Sam dug the pan out. This, of course, was a stupid thing to do.

“Holy Mary, Mother ofâ” The metal, naturally enough, was searing hot from the fire. He flung it away and jammed his burned fingers in his mouth. Jin appeared at his side, yanked his hand away from his face, and examined the red marks already coming up on his fingertips. She sighed.

So the evening ended with Sam back outside the Fata Morgana wagon, looking stupid while Jin coated his hand in burn cream and her uncle watched with his arms folded and his eyebrows raised, muttering something about what had possessed him to send Jin away in the company of this idiot boy.

At that, she raised her eyes to Sam's and gave him the slightest, smallest conspiratorial smile, which sent a blush over his face that he could only hope the old man would interpret as appropriate shame for being a stupid boy who burned himself on obviously hot pans.

“If you can, put ice on it when you get home,” she told him.

“Yes, ma'am.”

“Take the jar with you,” Liao instructed. “Use more tomorrow.”

“I'll bring it back,” Sam promised. Liao waved his hand dismissively and disappeared into the wagon.

“Can you come find me tomorrow?” Sam asked Jin the second her uncle was out of earshot.

“On the plaza, same as today?”

“Yes.”

She gave him one of her long, thoughtful looks. Then her face broke into a grin that made his stomach flip. “Yes, I think so.”

And then she was gone, up the stairs and into the wagon, and despite the pain in his hand and the horrible things that had happened earlier, Sam spent the long trek back to West Brighton feeling as though he were walking on air.