The Body Economic (6 page)

Authors: David Stuckler Sanjay Basu

The research team set out across the country to investigate. They saw signs that something was amiss when they reached the country's mono-industrial settlements (

mono-gorod

)âtowns set up by the Soviets to support its military and economy, where everything was planned to the last detail. The mono-towns were so named because they had only one business; the Communist Party had forced each village to specialize. Pitkyaranta, for example, was designed to mill lumber; Norilsk was a giant nickel factory; and several Siberian cities were customized for mining coal. One mining town, Kadykchan, was deep in Siberia's Magadan region. It had been built by Stalin's prisoners during World War II to provide coal for the Soviet military. Everything in the town revolved around the mines, and after the war the Soviets thought through all that would be needed for its residents: schools and hospitals next to the factories, housing for the workers and their families, and

even holiday resorts a short weekend's trip away. All of life necessities were in place, designed to support the town's sole purpose: extracting coal for the Soviet state.

When the research team reached Kadykchan and its neighboring towns, they found what looked like a post-Chernobyl disaster or a ghost town: windows broken, storefronts boarded up. A sculpture of Joseph Stalin's head that once gazed sternly atop the town hall had crumbled, his jaw eroded into a hollow cavity filled by birds' nests. Enormous Soviet steel mills had been stripped to pieces, frozen over into large, silenced blocks of ice. Inside the factory, metal tools had caked with rust, and factory floors had overgrown with tomato and potato plants, converted into a garden plot.

At their peak, the Soviet mono-towns had between 10,000 and 100,000 residents, depending on the needs of the industry. Kadykchan once had 11,000 residents. By 1989, at the time of the last Soviet census, the population numbered 6,000. In 2000, when the Russian demographers conducted their visit, there were under 1,000. The population now were mostly women, children, and

babushkas

(Russian grandmothers), peering curiously through the cracked windows.

Where had all the men gone?

2

The answer, it turned out, was hidden in the history of Russia's turbulent transition from a Soviet Socialist Republic to a Western market economy. The missing men were indicative of a broader collapse that had come with the rapid transition to a capitalist economy. It led to a massive tragedy in its own rightâa demographic crisis that still haunts Russia today, and one that was eminently avoidable. The post-communist mortality crisis resulted not from the decision to transition to capitalism, but from specific policy choices about how to manage that transition that turned out to have dire consequences.

In the early 1990s, Russia's economic system collapsed. Its GDP fell by more than a third, a catastrophe on a scale not seen in industrialized nations since the Great Depression in the United States. In terms of purchasing power, Russia's economy in the mid-1990s shrank to the equivalent of the US in 1897. While officially unemployment was zero in the Soviet era, it jumped to 22 percent by 1998. In 1995, government statistics found one-quarter of the population were living in poverty, but independent survey data revealed the poverty rate to be much higher, at more than 40 percent of the population. A decade after the transition to capitalism began, the World Bank estimated that one-quarter of the population were living on less than $2 per day,

and people living in the Soviet Union's former republics reported that they didn't have enough money to cover their basic nutrition.

3

As the Soviet Union began to disintegrate, the fall of one Soviet town's factory set in motion a domino-like chain reaction. Soviet mono-towns depended on each other for supplies and parts, materials that no other companies in the world manufactured. In time, as one firm went under, it bankrupted its dependent Soviet mono-towns. Virtually overnight, the whole purpose of the Soviet mono-town ceased to be. People were left stranded in remote corners of Siberia, thousands of miles from the large cities of Moscow and St. Petersburg. To survive, they ate potato peelings and foraged in the forests for roots and berries. And there was the boredom, endless boredom. People had nothing to do, nowhere to go, and little hope for a better future.

4

It was during that rapid transition that men began to die at an increasing rate. During Russia's move to the new market economy, men in towns and cities began to disappearânot old or frail men, but young men who would have otherwise been the vital force of the economy. The US Bureau of the Census had forecast that the Soviet Union's workforce would grow from 149 million in 1985 to 164 million in 1998âprojections that were correct until 1990, after which the actual numbers fell to 144 million in 1998.

5

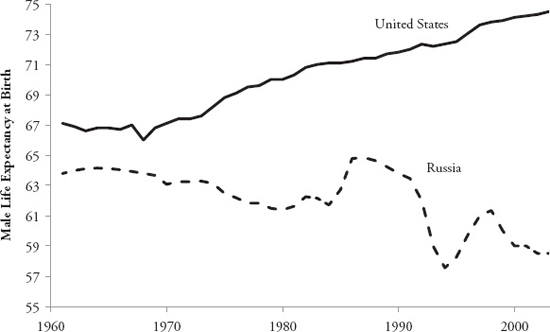

Soon after the population data became public in 1999, the UN's investigative team published their official report, warning that “a human crisis of monumental proportions is emerging in the former Soviet Union, as the transition years have literally been lethal for a great many people.” As shown in

Figure 2.1

, life expectancy among Russian men dropped from sixty-four to fifty-seven years of age between 1991 and 1994.

6

What became known as “the post-communist mortality crisis” turned out to be the worst drop in life expectancy in the past half-century in any country that wasn't an active war zone or experiencing a famine.

7

But the connection between the economic collapse of the mono-towns and the soaring death rates was not immediately clear. We had learned from the Great Depression that even a terrible market crash was no guarantee of a mortality crisis. So if a crashing economy didn't necessarily equate to a mass rise in deaths, what had caused so many Russian men to die during the economic depression of the 1990s?

We set out to investigate. Our first thought, as we looked into death certificates from this period, was that perhaps these data weren't real. The Soviet regime

was known to have kept its secrets; indeed, the KGB, the Soviet secret service police, could make a man disappear without a trace. Perhaps these men had been killed long ago and their deaths were only now coming to light, after the Russians let independent French and Russian demographers access the data to keep track. Or perhaps the Soviets had inflated their reports of the size of its male populationâseeking to intimidate Western countries about their prospects for military recruitment. (This was hardly a far-fetched idea: In 1976, the Communist Party had launched a Commission on the Non-Publication of Data, whose members argued, “We must not reveal the number of boys born. Our enemies could use this information. We must make it a state secret.”)

9

F

IGURE 2.1

Post-communist Mortality Crisis

8

To check whether the rise in death rates was genuine, we pored through troves of death certificates from before the fall of the USSR. We obtained data from the archives of the new government's demographic organization, Goskomstat. More than 90 percent of all deaths were reviewed and certified by doctors who were able to confirm each death and its cause, a rate higher than in many Western countries.

10

An unusual feature of the Russian crisis was that the deaths were concentrated in young, working-age men. Most disease outbreaks disproportionately affect vulnerable people, such as infants and the elderly. The rate of death

rose by a disconcerting 90 percent among the subgroup of men aged twenty-five to thirty-nine, in the prime of their lives.

Perhaps there was a terrible outbreak of influenza or other epidemic or widespread famineâor an as yet unknown pollutant from Soviet factories. But the death certificates that we, along with numerous other demographers, reviewed from Russia's statistical agencies did not support that theory. What the statistics showed was that many of these young men were dying from alcohol poisonings, suicides, homicides, and injuries. Such deaths seemed straightforward: men whose factories had shut down and were out of work were experiencing a high level of mental distress and anxiety, and their response was to turn to alcohol, harming themselves and others.

The young Russian men were also dying of heart attacks. This fact surprised us at first. We might have expected to see men in their fifties and sixties with clogged arteries having a heart attack, but rarely would people in their thirties and forties come to the hospitals with cardiovascular problems. The coroners' reports showed that the autopsies of the young men's arteries were clean. There was no plaque buildup. So what had caused the cardiovascular deaths?

To understand Russia's puzzling mortality patterns, we needed to look at different layers of health problems to understand their root causes. We wanted to move beyond identifying the immediate causes of death and their risk factors such as tobacco, unhealthy diets, and alcohol, to find the “causes of the causes,” the social and economic changes that led people to harm themselves and others.

Since these deaths happened very rapidly, our first suspicion was that Russian men may have “self-medicated” to cope with the stress of the economic downturnâconsuming huge amounts of vodka and home-brewed spirits. Russia has long had an epic drinking culture, one encouraged since the eighteenth century by the tsars to keep people from revolting. There's even a Russian word,

zapoi

, coined to describe the condition of being so drunk as to be incapacitated for days and even weeks at a time. More than three-quarters of all male industrial workers in Russia today would be considered “at-risk drinkers” by American medical criteria (that is, consuming more than four drinks on a single day).

11

Social stress and alcohol go hand in hand; alcohol is a well-known trigger of depression, suicide, and homicide. And alcohol might also explain the rising rate of heart attacks in the young men with clean arteries. Cardiologists

knew that in moderation, alcohol can reduce the risk of heart attacks; in large amounts, however, it provokes heart disease.

12

Russian politicians had tried to curb their country's alcohol problems. In 1985, the Soviet Union's leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, launched an anti-alcohol campaign. It was remarkably effective, immediately increasing overall life expectancy by three years. Not only did alcohol deaths fall, but tuberculosis and heart disease did as well, as alcoholics often experience these two conditions from crowded living conditions and the heart disease impact of heavy alcohol use. But the campaign proved so unpopular that it was abandoned in 1987. It was repealed in part to help raise government revenues from state sales of alcohol. Drinking increased after the program ended so that by 1992, when Russia began its transition to the market, Russian deaths from alcohol were back to their high levels as before 1985.

13

Even more troubling, it wasn't just the amount of alcohol Russian men were drinking during the early 1990sâit was the type. The form of alcohol changed, as men creatively found ways to binge without spending much money (they were, after all, mostly unemployed). Drinkers in Russia, Ukraine, and the Baltic states were drinking alcohols that were commercially manufactured using aftershave, mouthwash, and other products that contained alcohol but were not meant for consumption. These sources of alcohol were incredibly cheap and, unlike vodka and spirits, they weren't taxed. The brews from these alcohols were known as

odekolon

and were ostensibly sold as perfumes, but everybody knew what their real purpose was: they were labeled by flavor rather than scent, and had flip-top caps so that people could finish them easily in one sitting. These

odekolons

were particularly lethal: one study showed that drinking non-beverage alcohols increased the risk of death from alcoholic psychosis, liver cirrhosis, and heart disease by a factor of twenty-six over not drinking these substances.

14

Vladimir, an

odekolon

drinker from Pitkyaranta who lost his job when the town's paper mill went bankrupt, provided an illustrative example of the drinking culture at the time. He was known for passing out drunk on the floor of the town's abandoned mill after drinking for two weeks straight, often waking up in the hospital. Vladimir binged on cheap

odekolons

(while in more rural areas people drank home-distilled brews,

samogons

). People like Vladimir drank more and more during the early 1990s, even as their income dried up. When asked by a

New York Times

reporter why he continued to

drink, Vladimir said, “I can't explain it straightaway. I have a home. But I have nothing to do.”

15