The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (58 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Amazon.com, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Social History, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

6.31Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

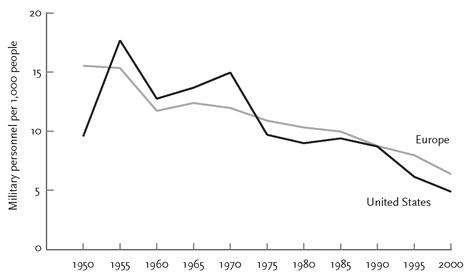

Another indicator of war-friendliness is the size of a nation’s military forces as a proportion of its population, whether enlisted by conscription or by television ads promising volunteers that they can be all that they can be. Payne has shown that the proportion of the population that a nation puts in uniform is the best indicator of its ideological embrace of militarism.

164

When the United States demobilized after World War II, it took on a new enemy in the Cold War and never shrank its military back to prewar levels. But figure 5–20 shows that the trend since the mid-1950s has been sharply downward. Europe’s disinvestment of human capital in the military sector began even earlier.

164

When the United States demobilized after World War II, it took on a new enemy in the Cold War and never shrank its military back to prewar levels. But figure 5–20 shows that the trend since the mid-1950s has been sharply downward. Europe’s disinvestment of human capital in the military sector began even earlier.

Other large countries, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, and China, also shrank their armed forces during this half-century. After the Cold War ended, the trend went global: from a peak of more than 9 military personnel per 100,000 people in 1988, the average across long-established countries plunged to less than 5.5 in 2001.

165

Some of these savings have come from outsourcing noncombat functions like laundry and food services to private contractors, and in the wealthiest countries, from replacing front-line military personnel with robots and drones. But the age of robotic warfare is far in the future, and recent events have shown that the number of available boots on the ground is still a major constraint on the projection of military force. For that matter, the roboticizing of the military is itself a manifestation of the trend we are exploring. Countries have developed these technologies at fantastic expense because the lives of their citizens (and, as we shall see, of foreign citizens) have become dearer.

165

Some of these savings have come from outsourcing noncombat functions like laundry and food services to private contractors, and in the wealthiest countries, from replacing front-line military personnel with robots and drones. But the age of robotic warfare is far in the future, and recent events have shown that the number of available boots on the ground is still a major constraint on the projection of military force. For that matter, the roboticizing of the military is itself a manifestation of the trend we are exploring. Countries have developed these technologies at fantastic expense because the lives of their citizens (and, as we shall see, of foreign citizens) have become dearer.

FIGURE 5–20.

Military personnel, United States and Europe, 1950–2000

Military personnel, United States and Europe, 1950–2000

Sources:

Correlates of War National Material Capabilities Dataset (1816–2001);

http://www.correlatesofwar.org

, Sarkees, 2000. Unweighted averages, every five years. “Europe” includes Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia/USSR, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, U.K., Yugoslavia.

Correlates of War National Material Capabilities Dataset (1816–2001);

http://www.correlatesofwar.org

, Sarkees, 2000. Unweighted averages, every five years. “Europe” includes Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia/USSR, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, U.K., Yugoslavia.

Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defenses of peace must be constructed.

—

UNESCO motto

Another indication that the Long Peace is no accident is a set of sanity checks which confirm that the mentality of leaders and populaces has changed. Each component of the war-friendly mindset—nationalism, territorial ambition, an international culture of honor, popular acceptance of war, and indifference to its human costs—went out of fashion in developed countries in the second half of the 20th century.

The first signal event was the 1948 endorsement of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights by forty-eight countries. The declaration begins with these articles:

Article 1.

All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.Article 2.

Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status. Furthermore, no distinction shall be made on the basis of the political, jurisdictional or institutional status of the country or territory to which a person belongs, whether it be independent, trust, nonself-governing or under any other limitation of sovereignty.Article 3

. Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person.

It’s tempting to dismiss this manifesto as feel-good verbiage. But in endorsing the Enlightenment ideal that the ultimate value in the political realm is the individual human being, the signatories were repudiating a doctrine that had reigned for more than a century, namely that the ultimate value was the nation, people, culture,

Volk

, class, or other collectivity (to say nothing of the doctrine of earlier centuries that the ultimate value was the monarch, and the people were his or her chattel). The need for an assertion of universal human rights had become evident during the Nuremberg Trials of 1945–46, when some lawyers had argued that Nazis could be prosecuted only for the portion of the genocides they committed in occupied countries like Poland. What they did on their own territory, according to the earlier way of thinking, was none of anyone else’s business.

Volk

, class, or other collectivity (to say nothing of the doctrine of earlier centuries that the ultimate value was the monarch, and the people were his or her chattel). The need for an assertion of universal human rights had become evident during the Nuremberg Trials of 1945–46, when some lawyers had argued that Nazis could be prosecuted only for the portion of the genocides they committed in occupied countries like Poland. What they did on their own territory, according to the earlier way of thinking, was none of anyone else’s business.

Another sign that the declaration was more than hot air was that the great powers were nervous about signing it. Britain was worried about its colonies, the United States about its Negroes, and the Soviet Union about its puppet states.

166

But after Eleanor Roosevelt shepherded the declaration through eighty-three meetings, it passed without opposition (though pointedly, with eight abstentions from the Soviet bloc).

166

But after Eleanor Roosevelt shepherded the declaration through eighty-three meetings, it passed without opposition (though pointedly, with eight abstentions from the Soviet bloc).

The era’s repudiation of counter-Enlightenment ideology was made explicit forty-five years later by Václav Havel, the playwright who became president of Czechoslovakia after the nonviolent Velvet Revolution had overthrown the communist government. Havel wrote, “The greatness of the idea of European integration on democratic foundations is its capacity to overcome the old Herderian idea of the nation state as the highest expression of national life.”

167

167

One paradoxical contributor to the Long Peace was the freezing of national borders. The United Nations initiated a norm that existing states and their borders were sacrosanct. By demonizing any attempt to change them by force as “aggression,” the new understanding took territorial expansion off the table as a legitimate move in the game of international relations. The borders may have made little sense, the governments within them may not have deserved to govern, but rationalizing the borders by violence was no longer a live option in the minds of statesmen. The grandfathering of boundaries has been, on average, a pacifying development because, as the political scientist John Vasquez has noted, “of all the issues over which wars could logically be fought, territorial issues seem to be the one most often associated with wars. Few interstate wars are fought without any territorial issue being involved in one way or another.”

168

168

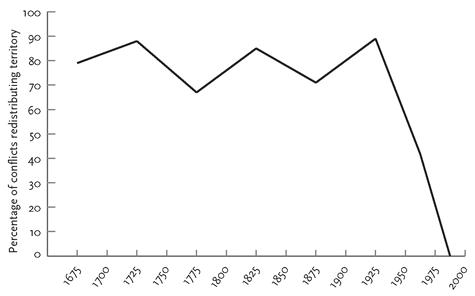

The political scientist Mark Zacher has quantified the change.

169

Since 1951 there have been only ten invasions that resulted in a major change in national boundaries, all before 1975. Many of them planted flags in sparsely populated hinterlands and islands, and some carved out new political entities (such as Bangladesh) rather than expanding the territory of the conqueror. Ten may sound like a lot, but as figure 5–21 shows, it represents a precipitous drop from the preceding three centuries.

169

Since 1951 there have been only ten invasions that resulted in a major change in national boundaries, all before 1975. Many of them planted flags in sparsely populated hinterlands and islands, and some carved out new political entities (such as Bangladesh) rather than expanding the territory of the conqueror. Ten may sound like a lot, but as figure 5–21 shows, it represents a precipitous drop from the preceding three centuries.

Israel is an exception that proves the rule. The serpentine “green line” where the Israeli and Arab armies stopped in 1949 was not particularly acceptable to anyone at the time, especially the Arab states. But in the ensuing decades it took on an almost mystical status in the international community as Israel’s one true correct border. The country has acceded to international pressure to relinquish most of the territory it has occupied in the various wars since then, and within our lifetimes it will probably withdraw from the rest, with some minor swaps of land and perhaps a complicated arrangement regarding Jerusalem, where the norm of immovable borders will clash with the norm of undivided cities. Most other conquests, such as the Indonesian takeover of East Timor, have been reversed as well. The most dramatic recent example was in 1990, when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait (the only time since 1945 that one member of the UN has swallowed another one whole), and an aghast multinational coalition made short work of pushing him out.

FIGURE 5–21.

Percentage of territorial wars resulting in redistribution of territory, 1651–2000

Percentage of territorial wars resulting in redistribution of territory, 1651–2000

Source:

Data from Zacher, 2001, tables 1 and 2; the data point for each half-century is plotted at its midpoint, except for the last half of the 20th century, in which each point represents a quarter-century.

Data from Zacher, 2001, tables 1 and 2; the data point for each half-century is plotted at its midpoint, except for the last half of the 20th century, in which each point represents a quarter-century.

The psychology behind the sanctity of national boundaries is not so much empathy or moral reasoning as norms and taboos (a topic that will be explored in chapter 9). Among respectable countries, conquest is no longer a thinkable option. A politician in a democracy today who suggested conquering another country would be met not with counterarguments but with puzzlement, embarrassment, or laughter.

The territorial-integrity norm, Zacher points out, has ruled out not just conquest but other kinds of boundary-tinkering. During decolonization, the borders of newly independent states were the lines that some imperial administrator had drawn on a map decades before, often bisecting ethnic homelands or throwing together enemy tribes. Nonetheless there was no movement to get all the new leaders to sit around a table with a blank map and a pencil and redraw the borders from scratch. The breakup of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia also resulted in the dashed lines between internal republics and provinces turning into solid lines between sovereign states, without any redrafting.

The sacralization of arbitrary lines on a map may seem illogical, but there is a rationale to the respecting of norms, even arbitrary and unjustifiable ones. The game theorist Thomas Schelling has noted that when a range of compromises would leave two negotiators better off than they would be if they walked away, any salient cognitive landmark can lure them into an agreement that benefits them both.

170

People bargaining over a price, for example, can “get to yes” by splitting the difference between their offers, or by settling on a round number, rather than haggling indefinitely over the fairest price. Melville’s whalers in

Moby-Dick

acceded to the norm that a fast-fish belongs to the party fast to it because they knew it would avoid “the most vexatious and violent disputes.” Lawyers say that possession is nine tenths of the law, and everyone knows that good fences make good neighbors.

170

People bargaining over a price, for example, can “get to yes” by splitting the difference between their offers, or by settling on a round number, rather than haggling indefinitely over the fairest price. Melville’s whalers in

Moby-Dick

acceded to the norm that a fast-fish belongs to the party fast to it because they knew it would avoid “the most vexatious and violent disputes.” Lawyers say that possession is nine tenths of the law, and everyone knows that good fences make good neighbors.

A respect for the territorial-integrity norm ensures that the kind of discussion that European leaders had with Hitler in the 1930s, when it was considered perfectly reasonable that he should swallow Austria and chunks of Czechoslovakia to make the borders of Germany coincide with the distribution of ethnic Germans, is no longer thinkable. Indeed, the norm has been corroding the ideal of the nation-state and its sister principle of the self-determination of peoples, which obsessed national leaders in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The goal of drawing a smooth border through the fractal of interpenetrating ethnic groups is an unsolvable geometry problem, and living with existing borders is now considered better than endless attempts to square the circle, with its invitations to ethnic cleansing and irredentist conquest.

Other books

The Rescue (Guardians of Ga'hoole) by Kathryn Lasky

Violins of Hope by James A. Grymes

Uglies by Scott Westerfeld

A Simple Truth by Ball, Albert

The Private Affairs Of Lady Jane Fielding by Viveka Portman

The Dead Mountaineer's Inn by Arkady Strugatsky

Murder on Old Main Street (Kate Lawrence Mysteries) by Ivie, Judith

The Shut Eye by Belinda Bauer

Forgotten Days (Fate's Intent Book 6) by Bowles, April

Where the Sea Used to Be by Rick Bass