The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (102 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Amazon.com, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Social History, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

11.79Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

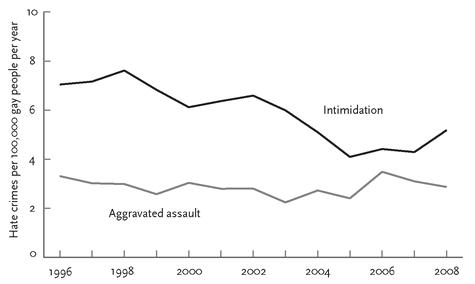

FIGURE 7–25.

Antigay hate crimes in the United States, 1996–2008

Antigay hate crimes in the United States, 1996–2008

Source:

Data from the annual FBI reports of Hate Crime Statistics (

http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.htm

). The number of incidents is divided by the population covered by the agencies reporting the statistics multiplied by 0.03, a common estimate of the incidence of homosexuality in the adult population.

Data from the annual FBI reports of Hate Crime Statistics (

http://www.fbi.gov/hq/cid/civilrights/hate.htm

). The number of incidents is divided by the population covered by the agencies reporting the statistics multiplied by 0.03, a common estimate of the incidence of homosexuality in the adult population.

So while we can’t say for sure that gay Americans have become safer from assault, we do know they are safer from intimidation, safer from discrimination and moral condemnation, and perhaps most importantly, completely safe from violence from their own government. For the first time in millennia, the citizens of more than half the countries of the world can enjoy that safety—not enough of them, but a measure of progress from a time in which not even helping to save one’s country from defeat in war was enough to keep the government goons away.

ANIMAL RIGHTS AND THE DECLINE OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALSLet me tell you about the worst thing I have ever done. In 1975, as a twenty-year-old sophomore, I got a summer job as a research assistant in an animal behavior lab. One evening the professor gave me an assignment. Among the rats in the lab was a runt that could not participate in the ongoing studies, so he wanted to use it to try out a new experiment. The first step was to train the rat in what was called a temporal avoidance conditioning procedure. The floor of a Skinner box was hooked up to a shock generator, and a timer that would shock the animal every six seconds unless it pressed a lever, which would give it a ten-second reprieve. Rats catch on quickly and press the lever every eight or nine seconds, postponing the shock indefinitely. All I had to do was throw the rat in the box, start the timers, and go home for the night. When I arrived back at the lab early the next morning, I would find a fully conditioned rat.

But that was not what looked back at me when I opened the box in the morning. The rat had a grotesque crook in its spine and was shivering uncontrollably. Within a few seconds, it jumped with a start. It was nowhere near the lever. I realized that the rat had not learned to press the lever and had spent the night being shocked every six seconds. When I reached in to rescue it, I found it cold to the touch. I rushed it to the veterinarian two floors down, but it was too late, and the rat died an hour later. I had tortured an animal to death.

As the experiment was being explained to me, I had already sensed it was wrong. Even if the procedure had gone perfectly, the rat would have spent twelve hours in constant anxiety, and I had enough experience to know that laboratory procedures don’t always go perfectly. My professor was a radical behaviorist, for whom the question “What is it like to be a rat?” was simply incoherent. But I was not, and there was no doubt in my mind that a rat could feel pain. The professor wanted me in his lab; I knew that if I refused, nothing bad would happen. But I carried out the procedure anyway, reassured by the ethically spurious but psychologically reassuring principle that it was standard practice.

The resonance with certain episodes of 20th-century history is too close for comfort, and in the next chapter I will expand on the psychological lesson I learned that day. The reason I bring up this blot on my conscience is to show what

was

standard practice in the treatment of animals at the time. To motivate the animals to work for food, we starved them to 80 percent of their freefeeding weight, which in a small animal means a state of gnawing hunger. In the lab next door, pigeons were shocked through beaded keychains that were fastened around the base of their wings; I saw that the chains had worn right through their skin, exposing the muscle below. In another lab, rats were shocked through safety pins that pierced the skin of their chests. In one experiment on endorphins, animals were given unavoidable shocks described in the paper as “extremely intense, just subtetanizing”—that is, just short of the point where the animal’s muscles would seize up in a state of tetanus. The callousness extended outside the testing chambers. One researcher was known to show his anger by picking up the nearest unused rat and throwing it against a wall. Another shared a cold joke with me: a photograph, printed in a scientific journal, of a rat that had learned to avoid shocks by lying on its furry back while pressing the food lever with its forepaw. The caption: “Breakfast in bed.”

was

standard practice in the treatment of animals at the time. To motivate the animals to work for food, we starved them to 80 percent of their freefeeding weight, which in a small animal means a state of gnawing hunger. In the lab next door, pigeons were shocked through beaded keychains that were fastened around the base of their wings; I saw that the chains had worn right through their skin, exposing the muscle below. In another lab, rats were shocked through safety pins that pierced the skin of their chests. In one experiment on endorphins, animals were given unavoidable shocks described in the paper as “extremely intense, just subtetanizing”—that is, just short of the point where the animal’s muscles would seize up in a state of tetanus. The callousness extended outside the testing chambers. One researcher was known to show his anger by picking up the nearest unused rat and throwing it against a wall. Another shared a cold joke with me: a photograph, printed in a scientific journal, of a rat that had learned to avoid shocks by lying on its furry back while pressing the food lever with its forepaw. The caption: “Breakfast in bed.”

I’m relieved to say that just five years later, indifference to the welfare of animals among scientists had become unthinkable, indeed illegal. Beginning in the 1980s, any use of an animal for research or teaching had to be approved by an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), and any scientist will confirm that these committees are not rubber stamps. The size of cages, the amount and quality of food and veterinary care, and the opportunities for exercise and social contact are strictly regulated. Researchers and their assistants must take a training course on the ethics of animal experimentation, attend a series of panel discussions, and pass an exam. Any experiment that would subject an animal to discomfort or distress is placed in a category governed by special regulations and must be justified by its likelihood of providing “a greater benefit to science and human welfare.”

Any scientist will also confirm that attitudes among scientists themselves have changed. Recent surveys have shown that animal researchers, virtually without exception, believe that laboratory animals feel pain.

240

Today a scientist who was indifferent to the welfare of laboratory animals would be treated by his or her peers with contempt.

240

Today a scientist who was indifferent to the welfare of laboratory animals would be treated by his or her peers with contempt.

The change in the treatment of laboratory animals is part of yet another rights revolution: the growing conviction that animals should not be subjected to unjustifiable pain, injury, and death. The revolution in animal rights is a uniquely emblematic instance of the decline of violence, and it is fitting that I end my survey of historical declines by recounting it. That is because the change has been driven purely by the ethical principle that one ought not to inflict suffering on a sentient being. Unlike the other Rights Revolutions, the movement for animal rights was not advanced by the affected parties themselves: the rats and pigeons were hardly in a position to press their case. Nor has it been a by-product of commerce, reciprocity, or any other positive-sum negotiation; the animals have nothing to offer us in exchange for our treating them more humanely. And unlike the revolution in children’s rights, it does not hold out the promise of an improvement in the makeup of its beneficiaries later in life. The recognition of animal interests was taken forward by human advocates on their behalf, who were moved by empathy, reason, and the inspiration of the other Rights Revolutions. Progress has been uneven, and certainly the animals themselves, if they could be asked, would not allow us to congratulate ourselves too heartily just yet. But the trends are real, and they are touching every aspect of our relationship with our fellow animals.

When we think of indifference to animal welfare, we tend to conjure up images of scientific laboratories and factory farms. But callousness toward animals is by no means modern. In the course of human history it has been the default.

241

241

Killing animals to eat their flesh is a part of the human condition. Our ancestors have been hunting, butchering, and probably cooking meat for at least two million years, and our mouths, teeth, and digestive tracts are specialized for a diet that includes meat.

242

The fatty acids and complete protein in meat enabled the evolution of our metabolically expensive brains, and the availability of meat contributed to the evolution of human sociality.

243

The jackpot of a felled animal gave our ancestors something of value to share or trade and set the stage for reciprocity and cooperation, because a lucky hunter with more meat than he could consume on the spot had a reason to share it, with the expectation that he would be the beneficiary when fortunes reversed. And the complementary contributions of hunted meat from men and gathered plants from women created synergies that bonded men and women for reasons other than the obvious ones. Meat also provided men with an efficient way to invest in their offspring, further strengthening family ties.

242

The fatty acids and complete protein in meat enabled the evolution of our metabolically expensive brains, and the availability of meat contributed to the evolution of human sociality.

243

The jackpot of a felled animal gave our ancestors something of value to share or trade and set the stage for reciprocity and cooperation, because a lucky hunter with more meat than he could consume on the spot had a reason to share it, with the expectation that he would be the beneficiary when fortunes reversed. And the complementary contributions of hunted meat from men and gathered plants from women created synergies that bonded men and women for reasons other than the obvious ones. Meat also provided men with an efficient way to invest in their offspring, further strengthening family ties.

The ecological importance of meat over evolutionary time left its mark in the psychological importance of meat in human lives. Meat tastes good, and eating it makes people happy. Many traditional cultures have a word for meat hunger, and the arrival of a hunter with a carcass was an occasion for village-wide rejoicing. Successful hunters are esteemed and have better sex lives, sometimes by dint of their prestige, sometimes by explicit exchanges of the carnal for the carnal. And in most cultures, a meal does not count as a feast unless meat is served.

244

244

With meat so important in human affairs, it’s not surprising that the welfare of the entities whose bodies provide that meat has been low on the list of human priorities. The usual signals that mitigate violence among humans are mostly absent in animals: they are not close kin, they can’t trade favors with us, and in most species they don’t have faces or expressions that elicit our sympathy. Conservationists are often exasperated that people care only about the charismatic mammals lucky enough to have faces to which humans respond, like grinning dolphins, sad-eyed pandas, and baby-faced juvenile seals. Ugly species are on their own.

245

245

The reverence for nature commonly attributed to foraging people in children’s books did not prevent them from hunting large animals to extinction or treating captive animals with cruelty. Hopi children, for example, were encouraged to capture birds and play with them by breaking their legs or pulling off their wings.

246

A Web site for Native American cuisine includes the following recipe:

246

A Web site for Native American cuisine includes the following recipe:

ROAST TURTLEIngredients:

One turtle

One campfireDirections:Put a turtle on his back on the fire.

When you hear the shell crack, he’s done.

247

The cutting or cooking of live animals by traditional peoples is far from uncommon. The Masai regularly bleed their cattle and mix the blood with milk for a delicious beverage, and Asian nomads cut chunks of fat from the tails of living sheep that they have specially bred for that purpose.

248

Pets too are treated harshly: a recent cross-cultural survey found that half the traditional cultures that keep dogs as pets kill them, usually for food, and more than half abuse them. Among the Mbuti of Africa, for example, “the hunting dogs, valuable as they are, get kicked around mercilessly from the day they are born to the day they die.”

249

When I asked an anthropologist friend about the treatment of animals by the hunter-gatherers she had worked with, she replied:

248

Pets too are treated harshly: a recent cross-cultural survey found that half the traditional cultures that keep dogs as pets kill them, usually for food, and more than half abuse them. Among the Mbuti of Africa, for example, “the hunting dogs, valuable as they are, get kicked around mercilessly from the day they are born to the day they die.”

249

When I asked an anthropologist friend about the treatment of animals by the hunter-gatherers she had worked with, she replied:

That is perhaps the hardest part of being an anthropologist. They sensed my weakness and would sell me all kinds of baby animals with descriptions of what they would do to them otherwise. I used to take them far into the desert and release them, they would track them, and bring them back to me for sale again!

The early civilizations that depended on domesticated livestock often had elaborate moral codes on the treatment of animals, but the benefits to the animal were mixed at best. The overriding principle was that animals exist for the benefit of humans. In the Hebrew Bible, God’s first words to Adam and Eve in Genesis 1:28 are “Be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” Though Adam and Eve were frugivores, after the flood the human diet switched to meat. God told Noah in Genesis 9:2–3: “The fear of you and the dread of you shall be upon every beast of the earth, and upon every fowl of the air, upon all that moveth upon the earth, and upon all the fishes of the sea; into your hand are they delivered. Every moving thing that liveth shall be meat for you; even as the green herb have I given you all things.” Until the destruction of the second temple by the Romans in 70 CE, vast numbers of animals were slaughtered by Hebrew priests, not to nourish the people but to indulge the superstition that God had to be periodically placated with a well-done steak. (The smell of charbroiled beef, according to the Bible, is “a soothing aroma” and “a sweet savor” to God.)

Other books

Rome Burning by Sophia McDougall

Stay With Me by Marchman, A. C.

Christmas With Mr. Jeffers by Julie Kavanagh

Colorblind (Moonlight) by Dubrinsky, Violette

The Towers of Love by Birmingham, Stephen;

The Nostradamus File by Alex Lukeman

The Forgotten 500 by Gregory A. Freeman

Más Allá de las Sombras by Brent Weeks

The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers Beneath the Queen's Window by Rachel Swirsky

Disappearances by Linda Byler