The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (98 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

12.29Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

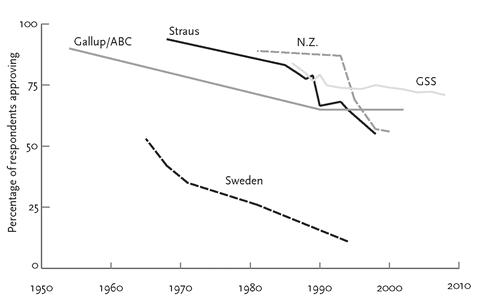

FIGURE 7–17.

Approval of spanking in the United States, Sweden, and New Zealand, 1954–2008

Approval of spanking in the United States, Sweden, and New Zealand, 1954–2008

Sources:

Gallup/ABC: Gallup, 1999; ABC News, 2002. Straus: Straus, 2001, p. 206. General Social Survey:

http://www.norc.org/GSS+Website/

, weighted means. New Zealand: Carswell, 2001. Sweden: Straus, 2009.

Gallup/ABC: Gallup, 1999; ABC News, 2002. Straus: Straus, 2001, p. 206. General Social Survey:

http://www.norc.org/GSS+Website/

, weighted means. New Zealand: Carswell, 2001. Sweden: Straus, 2009.

What about actual behavior? Many parents will still slap a toddler’s hand if the child reaches for a forbidden object, but in the second half of the 20th century every other kind of corporal punishment declined. In the 1930s American parents spanked their children more than 3 times a month, or more than 30 times a year. By 1975 the figure had fallen to 10 times a year and by 1985 to around 7.

182

Even steeper declines were seen in Europe.

183

In the 1950s, 94 percent of Swedes spanked their children, and 33 percent did so every day; by 1995, the figures had plunged to 33 and 4 percent. By 1992, German parents had come a long way from their great-grandparents who had placed their grandparents on hot stoves and tied them to bedposts. But 81 percent still slapped their children on the face, 41 percent spanked them with a stick, and 31 percent beat them to the point of bruising. By 2002, these figures had sunk to 14 percent, 5 percent, and 3 percent.

182

Even steeper declines were seen in Europe.

183

In the 1950s, 94 percent of Swedes spanked their children, and 33 percent did so every day; by 1995, the figures had plunged to 33 and 4 percent. By 1992, German parents had come a long way from their great-grandparents who had placed their grandparents on hot stoves and tied them to bedposts. But 81 percent still slapped their children on the face, 41 percent spanked them with a stick, and 31 percent beat them to the point of bruising. By 2002, these figures had sunk to 14 percent, 5 percent, and 3 percent.

There remains a lot of variation among countries today. No more than 5 percent of college students in Israel, Hungary, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Sweden recall being hit as a teenager, but more than a quarter of the students in Tanzania and South Africa do.

184

In general, wealthier countries spank their children less, with the exception of developed Asian nations like Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong. The international contrast is replicated among ethnic groups in the United States, where African Americans and Asians spank more than whites.

185

But the level of approval of spanking has declined in all three groups.

186

184

In general, wealthier countries spank their children less, with the exception of developed Asian nations like Taiwan, Singapore, and Hong Kong. The international contrast is replicated among ethnic groups in the United States, where African Americans and Asians spank more than whites.

185

But the level of approval of spanking has declined in all three groups.

186

In 1979 the government of Sweden outlawed spanking altogether.

187

The other Scandinavian countries soon joined it, followed by several countries of Western Europe. The United Nations and the European Union have called on

all

their member nations to abolish spanking. Several countries have launched public awareness campaigns against the practice, and twenty-four have now made it illegal.

187

The other Scandinavian countries soon joined it, followed by several countries of Western Europe. The United Nations and the European Union have called on

all

their member nations to abolish spanking. Several countries have launched public awareness campaigns against the practice, and twenty-four have now made it illegal.

The prohibition of spanking represents a stunning change from millennia in which parents were considered to own their children, and the way they treated them was considered no one else’s business. But it is consistent with other intrusions of the state into the family, such as compulsory schooling, mandatory vaccination, the removal of children from abusive homes, the imposition of lifesaving medical care over the objections of religious parents, and the prohibition of female genital cutting by communities of Muslim immigrants in European countries. In one frame of mind, this meddling is a totalitarian imposition of state power into the intimate sphere of the family. But in another, it is part of the historical current toward a recognition of the autonomy of individuals. Children are people, and like adults they have a right to life and limb (and genitalia) that is secured by the social contract that empowers the state. The fact that other individuals—their parents—stake a claim of ownership over them cannot negate that right.

American sentiments tend to weight family over government, and currently no American state prohibits corporal punishment of children by their parents. But when it comes to corporal punishment of children

by

the government, namely in schools, the United States has been turning away from this form ofof violence. Even in red states, where three-quarters of the people approve of spanking by parents, only 30 percent approve of paddling in schools, and in the blue states the approval rate is less than half that.

188

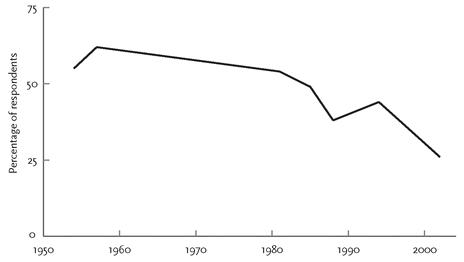

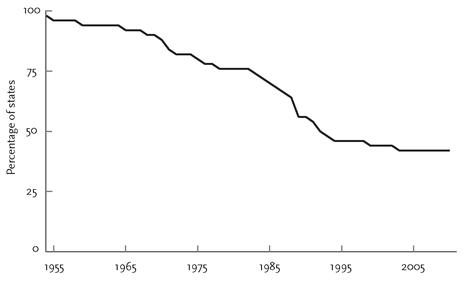

And since the 1950s the level of approval of corporal punishment in schools has been in decline (figure 7–18). The growing disapproval has been translated into legislation. Figure 7–19 shows the shrinking proportion of American states that still allow corporal punishment in schools.

by

the government, namely in schools, the United States has been turning away from this form ofof violence. Even in red states, where three-quarters of the people approve of spanking by parents, only 30 percent approve of paddling in schools, and in the blue states the approval rate is less than half that.

188

And since the 1950s the level of approval of corporal punishment in schools has been in decline (figure 7–18). The growing disapproval has been translated into legislation. Figure 7–19 shows the shrinking proportion of American states that still allow corporal punishment in schools.

FIGURE 7–18.

Approval of corporal punishment in schools in the United States, 1954–2002

Approval of corporal punishment in schools in the United States, 1954–2002

Sources:

Data for 1954–94 from Gallup, 1999; data for 2002 from ABC News, 2002.

Data for 1954–94 from Gallup, 1999; data for 2002 from ABC News, 2002.

FIGURE 7–19.

American states allowing corporal punishment in schools, 1954–2010

American states allowing corporal punishment in schools, 1954–2010

Source:

Data from Leiter, 2007.

Data from Leiter, 2007.

The trend is even more marked in the international arena, where corporal punishment in schools is now seen as a violation of human rights, like other forms of extrajudicial government violence. It has been condemned by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, the UN Human Rights Committee, and the UN Committee Against Torture, and has been banned by 106 countries, more than half of the world’s total.

189

189

Though a majority of Americans still endorse corporal punishment by parents, they draw an increasingly sharp line between mild violence they consider discipline, such as spanking and slapping, and severe violence they consider abuse, such as punching, kicking, whipping, beating, and terrorizing (for example, threatening a child with a knife or gun, or dangling it over a ledge). In his surveys of domestic violence, Straus gave respondents a checklist that included punishments that are now considered abusive. He found that the number of parents admitting to them almost halved between 1975 and 1992, from 20 percent of mothers to a bit more than 10 percent.

190

190

A problem in self-reports of violence by perpetrators (as opposed to self-reports by victims) is that a positive response is a confession to a wrongdoing. An apparent decline in parents beating their children may really be a decline in parents owning up to it. At one time a mother who left bruises on her child might consider it within the range of acceptable discipline. But starting in the 1980s, a growing number of opinion leaders, celebrities, and writers of television dramas began to call attention to child abuse, often by portraying abusive parents as reprehensible ogres or grown-up children as permanently scarred. In the wake of this current, a parent who bruised a child in anger might keep her mouth shut when the surveyor called. We do know that child abuse had become more of a stigma in this interval. In 1976, when people were asked, “Is child abuse a serious problem in this country?” 10 percent said yes; when the same question was asked in 1985 and 1999, 90 percent said yes.

191

Straus argued that the downward trend in his violence survey captured both a decline in the acceptance of abuse and a decline in actual abuse; even if much of the decline was in acceptance, he added, that would be something to celebrate. A decreasing tolerance of child abuse led to an expansion in the number of abuse hotlines and child protection officers, and to an expanded mandate among police, social workers, school counselors, and volunteers to look for signs of abuse and take steps that would lead to abusers being punished or counseled and to children being removed from the worst homes.

191

Straus argued that the downward trend in his violence survey captured both a decline in the acceptance of abuse and a decline in actual abuse; even if much of the decline was in acceptance, he added, that would be something to celebrate. A decreasing tolerance of child abuse led to an expansion in the number of abuse hotlines and child protection officers, and to an expanded mandate among police, social workers, school counselors, and volunteers to look for signs of abuse and take steps that would lead to abusers being punished or counseled and to children being removed from the worst homes.

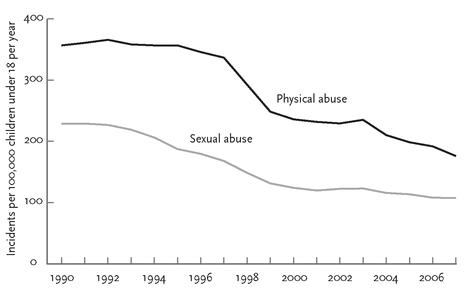

Have the changes in norms and institutions done any good? The National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System was set up to aggregate data on substantiated cases of child abuse from child protection agencies around the country. The psychologist Lisa Jones and the sociologist David Finkelhor have plotted their data over time and shown that from 1990 to 2007 the rate of physical abuse of children fell by half (figure 7–20).

FIGURE 7–20.

Child abuse in the United States, 1990–2007

Child abuse in the United States, 1990–2007

Sources:

Data from Jones & Finkelhor, 2007; see also Finkelhor & Jones, 2006.

Data from Jones & Finkelhor, 2007; see also Finkelhor & Jones, 2006.

Jones and Finkelhor also showed that during this time the rate of sexual abuse, and the incidence of violent crimes against children such as assault, robbery, and rape, also fell by a third to two-thirds. They corroborated the declining numbers with sanity checks such as victimization surveys, homicide data, offender confessions, and rates of sexually transmitted diseases, all of which are in decline. In fact over the past two decades the lives of children and adolescents improved in just about every way you can measure. They were also less likely to run away, to get pregnant, to get into trouble with the law, and to kill themselves. England and Wales have also enjoyed a decline in violence against children: a recent report has shown that since the 1970s, the rate of violent deaths of children fell by almost 40 percent.

192

192

The decline of child abuse in the 1990s coincided in part with the decline of adult homicide, and its causes are just as hard to pinpoint. Finkelhor and Jones examined the usual suspects. Demography, capital punishment, crack cocaine, guns, abortion, and incarceration can’t explain the decline. The prosperity of the 1990s can explain it a little, but can’t account for the decline in sexual abuse, nor a second decline of physical abuse in the 2000s, when the economy was in the tank. The hiring of more police and interveners from social service agencies probably helped, and Finkelhor and Jones speculate that another exogenous factor may have made a difference. The early 1990s was the era of Prozac Nation and Running on Ritalin. The massive expansion in the prescription of medication for depression and attention deficit disorder may have lifted many parents out of depression and helped many children control their impulses. Finkelhor and Jones also pointed to nebulous but potentially potent changes in cultural norms. The 1990s, as we saw in chapter 3, hosted a civilizing offensive that reversed some of the licentiousness of the 1960s and made all forms of violence increasingly repugnant. And the Oprahfication of America applied a major stigma to domestic violence, while destigmatizing—indeed beatifying—the victims who brought it to light.

Other books

Pressure by Jeff Strand

The Cannabis Breeder's Bible by Greg Green

Prowling the Vet by Tamsin Baker

When We Were Real (Author's Preferred Edition) by William Barton

Mars Prime by William C. Dietz

Blue Dawn by Perkin, Norah-Jean

The Italian Matchmaker by Santa Montefiore

The Shocking Truth About Ramsey by Ray, Jennifer L.

Nefertiti by Nick Drake

Disturbia (The 13th) by Manuel, Tabatha