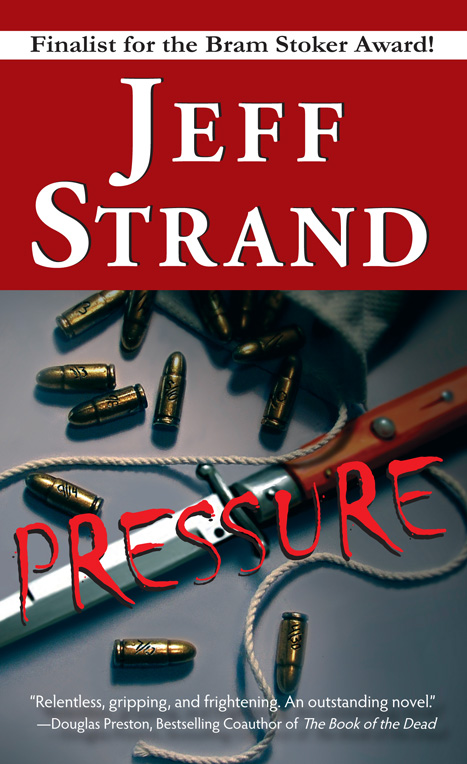

Pressure

PRESSURE

LEISURE BOOKS NEW YORK CITY

NEW YORK CITY

The woman whimpered and cried softly.

“I’m not doing it,” I said to Darren. “You might as well just let her go.”

Darren shook his head. “I’m not gonna let her go. We both know that. But I’m also not going to make you slice her up at gunpoint. Instead, we’re going to do this as a game. See the dresser next to the bed? Open the top drawer.”

“No.”

“Goddamn it Alex, don’t get all resistant on me! Open the drawer!”

Avoiding the woman’s eyes, I stepped over to the dresser and opened the top drawer.

Inside was a brand new, shiny hatchet.

“It’s yours,” Darren said. “Take it.”

I picked up the hatchet and clenched it in my fist, wanting nothing more than to hurl it at him, to imbed it in his throat.

“Here’s the game,” he said. “We’re going to let her loose in the yard. You have ten minutes to bring me back her head. Nothing else; just her head…”

This book is dedicated to my mother.

(I’d previously dedicated

How to Rescue a Dead Princess

to her, but she’ll like this one better.)

Simplicity is hard.

Sometimes the easiest story to tell is the most complicated. Fill multiple plotlines with dozens of characters, and you’re guaranteed unending variety. If one plot stalls, switch to a fresh one. You’ve always got an escape hatch.

But what if you have only a handful of characters, all seen from a single narrator’s point of view? What if your story involves one central relationship, which gradually—and ominously—changes and deepens over time?

That’s when it gets tough. And if your story plays out over an extended period—not weeks or months, but years or decades—then it’s even tougher.

A lot of writers wouldn’t tackle that project. Maintaining tight focus in a story that spans a generation is an intimidating prospect. On the other hand, if you can pull it off, you’ve done something really hard. And really special.

In

Pressure

, Jeff Strand pulls it off.

He gives us a narrator we instantly identify with: the good kid briefly tempted to go just a little bit bad.

And this passing weakness inaugurates a sequence of events that culminates, years later, in passionate hatred and raging violence.

The swift, remorseless unfolding of the story might be almost intolerably intense if it weren’t relieved by humor. Fortunately, there’s enough of it to keep us from going crazy. The narrator’s wry awareness of his own foibles is the lifeline we cling to as we plunge into these dark waters.

But it’s a slender lifeline. By the end, there’s not much to smile about.

Pressure

takes us to a place we don’t want to be, in the company of a hero we wouldn’t want to be without.

The title tells you in one word what the book is all about. There’s the ticking-bomb pressure of a one-on-one relationship that’s increasingly out of control. There’s the chronic itchy-palms pressure of waiting, with paranoid certainty, for things to get bad, really bad. And there’s the more subtle pressure of social conformity, the pressure to disregard your own scruples and instincts in order to make or keep a friend. This last is the deadliest pressure of all, because without it, the nightmare would never get started.

It would be simplicity itself for our hero to wave off that social pressure and just walk away, saving himself.

But doing what’s simple—well, it’s hard.

Jeff Strand knows that. After reading

Pressure

, so will you.

Michael Prescott

November 2005

For a while, the bullets were the only things keeping me alive.

It was a sack of one hundred and fourteen of them, each with a date scratched onto the casing. The first date was nearly four months ago, a Thursday. I’d spent that entire morning in the bathtub, tears streaming down my face, the barrel of a revolver in my mouth, garbage bags taped to the wall so the landlord wouldn’t have to repaint. I wasn’t sure that I really wanted to commit suicide, but yet I couldn’t force myself to pry the gun barrel from between my teeth.

Finally I did pull the gun away and removed the bullet. Then I scratched 12/25 onto the casing with a pocketknife, as a reminder that I hadn’t killed myself that day.

I was in the bathtub even longer on Friday, but I still didn’t shoot myself. This time I wanted to. Desperately. I was biting down so hard on the barrel that when my front tooth cracked I thought for a second that the gun had fired. I’m not sure what ultimately kept me from pulling the trigger—probably cowardice—but in the end I had a second unused bullet and another date.

This became a daily ritual. Sometimes it got really, really bad. There were times, usually late at night, when the only thing keeping me from killing myself was the sight of the bag of bullets, the knowledge that I’d survived each of those days, so why couldn’t I survive just one more?

Other times I’d casually put the gun to my head for half a second and then plop down on the couch and watch some TV.

As the sack of bullets grew heavier, it became easier not to want to pull the trigger. My life became less about escape and more about the realization that I couldn’t hide away forever. I didn’t need to. I’d made it through one hundred and fourteen days.

On the hundred and fifteenth day, I decided that I probably had better things to spend my money on than bullets I wasn’t shooting. That freakishly cold evening I dropped the revolver in the sack, tied it tight, and walked six miles to the Winston Bridge. As I tried to ignore the happy father walking on the other side, his daughter perched up on his shoulders, I prepared to fling the sack into the pond below and begin a new era of my life.

Then I thought, no, bad idea. The last thing I needed was for the sack to wash up onshore and some kids to find it. I’d just have to begin this new era of my life without a symbolic act.

I looked at the father again, burst into tears, and walked to the nearest bar, where I got so drunk that I knocked myself unconscious when I fell off the bar stool. I woke up outside with blood in my eyes and the change missing from my pockets.

I’m sure I would have shot myself right then and there, except that the bastards had also taken the sack with my gun and bullets.

I just lay on the ground, shivering, unable to see anything beyond my breath misting in the air, trying to remember if there had ever been happy times.

There had been. In fact, there’d been wonderful times.

But that’s not where the story begins.

CHILDREN

“That’s all you’ve gotta do. Steal the condoms and you’re in the club.”

I nervously shifted my weight on the propped-up bicycle as we waited across the street (a dirt road that seemed to be comprised of one part dirt, nine parts jagged rocks) from the small drugstore. “I don’t know. Can’t I just steal a candy bar or something?”

Paul shook his head. “It’s gotta be rubbers.”

“But what if I get caught? I could go to jail.”

Marty chuckled. “Then you can be an honorary member from your cell.”

I sighed. At age twelve, I knew the basic function of the product they were asking me to shoplift, but I also knew that we weren’t going to be getting any actual use out of it.

“How about this? I’ll steal

three

candy bars. That’s a lot harder, don’t you think?”

“If we wanted candy bars, we could just buy candy bars,” Paul explained, scratching the stick-on cobra tattoo on his right arm and then pushing up his thick glasses. “And it’s not going to be hard. He’s half blind.”

“But what are you going to do with them?”

“What do you think?” Marty asked. “Use them.”

“You are not.”

“Sure we are. They make great water balloons.”

“C’mon, guys,” I protested. “Let me steal something else. Anything else.”

Paul nodded. “Okay, steal a box of Maxi Pads.”

“No way.”

“Rubbers or Maxi Pads. Your choice.”

If I’d still lived in Dayton, Ohio, I wouldn’t so much as stolen a soggy straw wrapper for the privilege of hanging out with kids like Paul and Marty. They were both gargantuan nerds who’d somehow convinced themselves that they belonged to the tough-guy crowd. The first time I ever saw Marty, he was sucking on his inhaler after an unsuccessful attempt to rough up a ten-year-old for his lunch money. Paul’s mom still cut the crusts off his peanut butter and jelly sandwiches and included a daily note expressing her motherly love, though he always made a big show of crumpling it up and throwing it into the garbage.

But Trimble, Arizona, population 6000, was not an easy place for a newcomer. The children all knew each other, and had known each other their entire lives. The cliques were firmly in place. There was no room for a skinny, introverted, completely non-athletic kid with an ugly purple birthmark covering his chin. I’d sat by myself at lunch for three full weeks, hoping somebody would take pity on me, but the other kids seemed perfectly content to go on pretending that I either didn’t exist or carried a communicable disease, perhaps one with an oozing flesh motif.

So when Paul and Marty asked me to go on a bike ride one day after school, I enthusiastically agreed.

“Chicken!” said Paul. “Chick-chick-chick-chicken!” He tucked his hands under his armpits and began making what he apparently thought were chicken noises.

“You sound like a duck,” Marty told him.

“I do not.”

“Then you sound like a retarded chicken.”

“I do not.”

“Okay, you sound like a

special

chicken.”

“What does that mean?” Paul asked.

“A retarded chicken.”

“Kiss my ass.”

My fervent hope was that this conversation would continue until it was time for us to go home for dinner, but unfortunately “kiss my ass” turned out to be its natural conclusion. “Do it, Alex,” said Paul. “Otherwise you don’t get to be in the club.”

“I don’t even want to be in the club.”

“Yeah, right.”

Yeah, right. “Are you sure he’s half blind?”

“He probably won’t even look up,” Marty insisted. “We steal stuff from him all the time.”

My stomach was churning and I could feel a headache coming on, but I nodded, slung my backpack over my shoulder, and silently walked toward the drugstore. This was stupid. This was so stupid. This was truly, deeply, incredibly, astoundingly, jaw-droppingly stupid.

But I was going to do it.

A bell tinkled as I pushed open the door. Mr. Greystein looked up from his

Christian Living

magazine and frowned. From the way Paul and Marty had been talking, I’d expected some shriveled geezer in his nineties, but Mr. Greystein didn’t look any older than fifty.

The drugstore was small and poorly lit; not much more than three aisles and a cooler. Behind Mr. Greyste in was a display of cigarettes. “Leave it at the counter,” he said.

“What?”

“Your backpack. Leave it at the counter.”

I walked over and placed my backpack on the counter. Since the backpack was to be the vessel through which my dastardly crime would be committed, this wasn’t a good development.

Mr. Greystein glared at me for a moment longer, and then returned his attention to his magazine. I walked over and pretended to look over the candy selection.

The boxes of condoms were on a rack right next to the front counter. Even if I’d had my backpack, they’d be nearly impossible to swipe. How could I possibly do this? Why was I even willing to try?

My stomach had gone from the churning sensation to outright pain, and the headache was throbbing with full force. I read the nutrition information on a Snickers bar while I tried to decide what to do.

Just leave. Who cared what Marty and Paul thought? Maybe if I bought them each a candy bar, they’d let me join the club anyway; after all…

Then I realized something that should have been obvious from the beginning. I didn’t need to steal the condoms. I could just buy them. Marty and Paul would never know that they weren’t stolen merchandise. I could be a liar instead of a thief.

Of course, not having researched prophylactic purchasing restrictions, I wasn’t sure if it was legal for a twelve-year-old to buy them. This wasn’t like alcohol or cigarettes, was it?

Quickly, before I lost my nerve, I returned to the register. I grabbed a random box of condoms, set it on the front counter, and then set the Snickers bar next to the box as if that might distract Mr. Greystein from my other purchase.

He regarded me for a long moment.

“How old are you?”

“Twelve.”

“Do your parents know you’re buying these?”

I shook my head.

“Don’t you think you’re a little young?”

I shrugged.

“I think you’re a

lot

young. I really don’t think I should be selling you these. I can’t imagine that a boy your age is responsible enough for that kind of thing, can you?”

I shrugged again.

He stared at me for a moment longer, and then his mouth curled up into the beginning of a smile.

“See, I don’t think you’ve fully considered this purchase,” he said, tapping the box. “These are lambskin condoms, which aren’t as trustworthy as the latex variety. The only reason you would want these is if you or your partner had an allergy to latex. Do you or your partner have an allergy to latex?”

I didn’t respond.

“Don’t be shy. If you’re not comfortable discussing the product, you’re certainly not comfortable using it. Do you or your partner have an allergy to latex?”

“No, sir.”

“Well, then, this isn’t what you want.” He shoved the box aside, leaned over the counter, and retrieved another box. “Now, this brand is ribbed for her pleasure. Do you know what ribbed means?”

“No.” My ears were ringing so loudly that I could barely hear him.

“It means that it has ridges that help with stimulation. That’s definitely something you want. It’s only common courtesy. I’m not sure about spermicidal lubricant…you seem like you might be too young for that even to be a problem, although I guess by the time you work through the entire box it could be a different story. What do you think?”

“I don’t know.”

“You can’t be an informed consumer with an attitude like that. You wouldn’t just grab any old candy bar off the shelf, would you? You’d make sure that if you were in the mood for peanuts, it had peanuts, or if you wanted nougat, that it had nougat, and so on, right?”

“I guess so.”

“Of course so. May I ask your name?”

“Alex.”

“Tell me, Alex, do you honestly feel that you’re ready to buy these condoms? Or should you maybe call the whole idea off? The

whole

idea, if you know what I mean.”

I like to call what happened next the trigger event for everything else that was to happen in my life. That’s probably not accurate. The trigger could have been agreeing to steal the condoms in the first place, or meeting Paul and Marty, or my parents moving us to Trimble, or, hell, just my being born if you wanted to get technical about it. However, I can say with absolute certainty that in twelve years of a life that included no small number of poor judgment calls, this was far and away the worst decision I’d made up to that point.

I grabbed the box of condoms and ran.

I shoved open the door at full speed and sprinted across the dirt road toward Paul and Marty. “Go!” I screamed. “Get out of here! Go, quick!”

They took off riding without hesitation, knocking over my bicycle in the process. Nearly hyperventilating with panic, I pulled it upright, jumped on, and began frantically pedaling after them.

I didn’t dare look behind me because I just

knew

that Mr. Greystein was standing outside of his drugstore, holding a shotgun, not afraid to use it, even on a kid.

I cringed and gritted my teeth, waiting for the sound of the shotgun blast and the unwelcome sensation of my head being blown apart.

It didn’t come, but I still didn’t turn around. Maybe the only thing preventing my death was his unwillingness to shoot me in the back.

Would he call the police?

Would they be able to find me?

Of course they would. In a town this small, the police would have no problem finding a shoplifter based on Mr. Greystein’s physical description…

…especially when the idiot shoplifter had left his backpack right there on the counter.

I squeezed the hand brakes, leaned over, and threw up onto the dirt.

Just go back there. Return the condoms, apologize, and beg him not to call the police. Tell him you’ll pay twice as much as they cost…three times, if he wants. You don’t have that much right now, but next week when you get your allowance…

Marty and Paul, far ahead, turned the corner and vanished from sight.

Still no sound of a shotgun.

I needed to go back.

Instead, I threw up again, and then rode home as fast as I could.

I parked my bicycle behind the house in case Mr. Greystein drove around looking for it. Since he had access to my name and address in multiple places in my backpack, it was unlikely that he’d resort to prowling the town looking for my bicycle, but I wasn’t exactly thinking at maximum logical capacity. Then I went to my room, sat on my bed, and stared at my pillow for the next hour until I was called to dinner.

“Did you get your homework done?” my father asked, disinterestedly, taking a bite of broccoli.

“Most of it.”

“Why not all of it?”

“Too hard.” Not to mention that Mr. Greystein was probably rifling through my backpack at this very moment.

My father made no comment and took another bite.

The phone rang.

My stomach lurched.

My mother got up, pushed back her hair, and went into the kitchen to answer.

I tried to scoop up a forkful of macaroni and cheese, but I couldn’t force my hand to work. Even if I could, I didn’t see any possibility of swallowing it without puking again.

I waited, desperately listening for some sign to indicate who my mother was talking to. The police wouldn’t phone beforehand, would they? “

Hi, Mrs. Fletcher, this is the law. We’re on our way to apprehend your son, so if you’ve got any furniture you don’t want riddled with bullet holes, we recommend that you move it into the garage as soon as you can.

”

“Mmmm-hmmm,” my mom said from the kitchen.

Then she laughed.

Thank God. It wasn’t about me. Unless the person on the other end had used some light humor to break the ice before informing my mother that her son was a wanted criminal.

My mother talked on the phone for less than a minute and then returned to dinner. I told her that I had a stomachache (the truth) and was excused from the table.

The next morning my stomachache was worse than ever, like I’d spent the night swallowing shards of glass with a chaser of rusty nails. I had to go to school anyway.

I talked to Paul and Marty briefly at lunch. That is, they talked to me, laughing about our close call and welcoming me into the club, while I silently kept a close watch on the lunchroom entrance, waiting for Mr. Greystein to show up, flanked by a pair of armed police officers.

Because I didn’t have any of my homework or textbooks, I received two hours of detention, which was a long time to sit after school with nothing to do but worry about whether or not Mr. Greystein had contacted my parents.

When I finally got home, he was seated on the living room sofa.

I immediately burst into tears.

“Go to your room,” said my mother, sounding neither angry nor upset. Her voice was barely audible, which was unusual for her. “Your backpack is at the foot of the stairs. Do your homework.”

I grabbed my backpack, ran upstairs, sat in my doorway, and tried to listen in on the conversation below.

I could only catch quick pieces. “…a good kid…” I heard Mr. Greystein say.

“…no excuse…” said my father.

“…a tough age…” said Mr. Greystein.

And finally, perfectly clear from my father: “We’ll take care of it.”

The front door opened, and then closed.

I sat there, waiting to be called downstairs for my unimaginable punishment.

Five minutes passed. Ten minutes. Twenty.

This was going to be a scary one if it was taking them this long to decide. Usually my mother could blurt out punishments mere seconds after the offending action, or, just as often, before the infraction even occurred. Of course, I’d never done anything nearly this bad before, so there was no precedent for this level of discipline.

One hour.

I wasn’t called down to dinner.

I didn’t dare go downstairs.

Two hours. Three.

I went to bed. I didn’t sleep.