The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (67 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

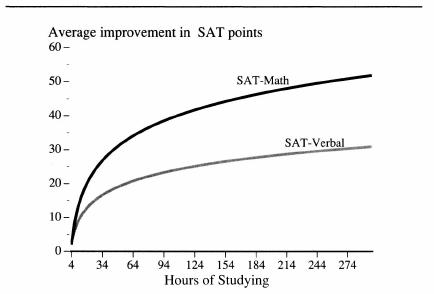

The diminishing returns to coaching for the SAT

Source:

Messick and Jungeblut 1981, Figs. 1, 3.

Although intended for utterly different purposes, the benefits of the Venezuelan program and of SAT coaching schools are remarkably similar. The sixty lessons of the Venezuelan course, representing forty-five hours of study, added between .1 and .4 standard deviation on various intelligence tests. From the figure on SAT coaching, we estimate that 45 hours of studying adds about .16 standard deviation to the Verbal score and about .23 standard deviation to the Math score.

46

These increases in test scores represent a mix of coaching effects—“cramming” is the process, with a quite temporary effect, that you may remember from school days—and perhaps an authentic increase in intelligence. We also are looking at short-term results here and must keep in mind that whenever test score follow-ups have been available (see the next section), the gains fade out. The net result is that any plausible estimate of the long-term increase in real cognitive ability must be small, and it is possible to make the case that it approaches zero.

Taken together, the negative findings about the effects of natural variation in schools, the findings of no effect except maybe to slow the falling-behind process in the evaluations of compensatory education, and the results of the Venezuelan and SAT coaching efforts all point to the same conclusion: As of now, the goal of raising intelligence among school-age children more than modestly, and doing so consistently and affordably, remains out of reach.

During the 1970s when scholars were getting used to the disappointing results of programs for school-age children, they were also coming to a consensus that IQ becomes hard to budge at about the time children go to school. Longitudinal studies found that individual differences in IQ stabilized at approximately age 6.

47

Meanwhile, developmental psychologists

found that the year-to-year correlations in mental test performance were close to zero in the first few years of life and then rose to asymptotic levels by age 6.

48

These findings conformed with the intuitive notion that, in the poet’s words, “as the twig is bent the tree’s inclined.”

49

Any intervention designed to increase intelligence (or change any other basic characteristics of the child) must start early, and the earlier the better.

50

Here, we will characterize the more notable attempts to help children through preschool interventions and summarize the expert consensus about them.

H

EAD

S

TART.

One of the oldest, largest, and most enduring of the contemporary programs designed to foster intellectual development came about as the result of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, the opening salvo of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. A year later, the mandated executive agency, the Office of Economic Opportunity, launched Project Head Start, a program intended to break the cycle of poverty by targeting preschool children in poor families.

51

Designed initially as a summer program, it was quickly converted into a year-long program providing classes for raising preschoolers’ intelligence and communication skills, giving their families medical, dental, and psychological services, encouraging parental involvement and training, and enriching the children’s diets.

52

Very soon, thousands of Head Start centers employing tens of thousands of workers were annually spending hundreds of millions of dollars at first, then billions, on hundreds of thousands of children and their families.

The earliest returns on Head Start were exhilarating. A few months spent by preschoolers in the first summer program seemed to be producing incredible IQ gains—as much as ten points.

53

The head of the Office of Economic Opportunity

54

reported the gains to Congress in the spring of 1966, and the program was expanded. By then, however, experts were noticing the dreaded “fade-out,” the gradual convergence in test scores of the children who participated in the program with comparable children who had not. To shorten a long story, every serious attempt to assess the impact of Head Start on intelligence has found fade-out.

55

Cognitive benefits that can often be picked up in the first grade of school are usually gone by the third grade. By sixth grade, they have vanished entirely in aggregate statistics.

Head Start programs, administered locally, vary greatly in quality. Perhaps, some have suggested, the good programs are raising intelligence, but their impact is diluted to invisibility in national statistics.

56

That remains possible, but it becomes ever less probable as time passes without any clear evidence for it emerging. To this point, no lasting improvements in intelligence have ever been statistically validated with

any

Head Start program. Many of the commentators who praise Head Start value its family counseling and public health benefits, while granting that it does not raise the intelligence of the children.

57

One response to the disappointment of Head Start has been to redefine its goals. Instead of raising intelligence, contemporary advocates say it reduces long-term school failure, crime, and illegitimacy and improves employability.

58

These delayed benefits are called sleeper effects, and they are what presumably justify the frequent public assertions that “a dollar spent on Head Start earns three dollars in the future,” or words to that effect.

59

But even these claims do not survive scrutiny. The evidence for sleeper effects, such as it is, almost never comes from Head Start programs themselves but from more intensive and expensive preschool interventions.

60

P

ERRY

P

RESCHOOL.

The study invoked most often as evidence that Head Start works is known as the Perry Preschool Program. David Weikart and his associates have drawn enormous media attention for their study of 123 black children (divided into experimental and control groups) from the inner city in Ypsilanti, Michigan, whose IQs measured between 70 and 85 when they were recruited in the early 1960s at the age of 3 or 4.

61

Fifty-eight children in the program received cognitive instruction five half-days

62

a week in a highly enriched preschool setting for one or two years, and their homes were visited by teachers weekly for further instruction of parents and children. The teacher-to-child ratio was high (about one to five), and most of the teachers had a master’s degree in appropriate child development and social work fields. Perry Preschool resembled the average Head Start program as a Ferrari resembles the family sedan.

The fifty-eight children in the experimental group were compared with another sixty-five who served as the control group. By the end of their one or two years in the program, the children who went to preschool were scoring eleven points higher in IQ than the control group. But by the end of the second grade, they were just marginally

ahead of the control group. By the end of the fourth grade, no significant difference in IQ remained.

63

Fadeout again.

Although this intensive attempt to raise intelligence failed to produce lasting IQ gains, the Ypsilanti group believes it has found evidence for a higher likelihood of high school graduation and some post-high school education, higher employment rates and literacy scores, lower arrest rates and fewer years spent in special education classes as a result of the year or two in preschool. The effects are small and some of them fall short of statistical significance.

64

They hardly justify investing billions of dollars in run-of-the-mill Head Start programs.

O

THER

L

ONGITUDINAL

S

TUDIES OF

P

RESCHOOL

P

ROGRAMS.

One problem faced by anyone who tries to summarize this literature is just like that faced by people trying to formulate public policy. With hundreds of studies making thousands of claims, what can be concluded? We are fortunate to have the benefit of the efforts of a group of social scientists known as the Consortium for Longitudinal Studies. Initially conceived by a Cornell professor, Irving Lazar, the consortium has pulled together the results of eleven studies of preschool education (including the Perry Preschool Project), chosen because they represent the best available scientifically.

65

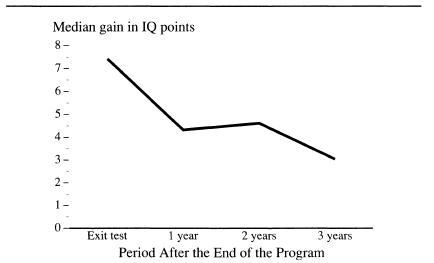

None of them was a Head Start program, but a few were elaborations of Head Start, upgraded and structured to lend themselves to evaluation, as Head Start programs rarely do. The next figure summarizes the cognitive outcomes in the preschool studies that the consortium deemed suitable for follow-up IQ analysis. The reported changes control for pretest IQ score, mother’s education, sex, number of siblings, and father presence.

Soon after completing one of these high-quality experimental preschool programs, the average child registers a net gain in IQ of more than seven IQ points, almost half a standard deviation. The gain shrinks to four to five points in the first two years after the program, and to about three points in the third year.

66

The consortium also collected later follow-up data that led the researchers to conclude that “the effect of early education on intelligence test scores was not permanent.”

67

The preschool programs we have just described were targeted at disadvantaged children in general. Now we turn to two studies that are more intensive than even the ones analyzed by the consortium and deal with

children who are considered to be at high risk of mental retardation, based on their mothers’ low IQs and socioeconomic deprivation.

IQ gains attributable to the Consortium preschool projects

Source:

Lazar and Darlington 1982, Table 15.

A case can be made for expecting interventions to be especially effective for these children, since their environments are so poor that they are unlikely to have had any of the benefits that a good program would provide. Moreover, if the studies have control groups and are reasonably well documented, there is at least a hope of deciding whether the programs succeeded in forestalling the emergence of retardation. We will briefly characterize the two studies approximating these conditions that have received the most scientific and media attention.

T

HE

A

BECEDARIAN

P

ROJECT.

The Carolina Abecedarian Project started in the early 1970s, under the guidance of Craig Ramey and his associates, then at the University of North Carolina.

68

Through various social agencies, they located pregnant women whose children would be at high risk for retardation. As the babies were born, the ones with obvious neurologic disorders were excluded from the study, but the remainder were assigned to two groups, presumably randomly. In all, there were four cohorts of experimental and control children. Both groups of babies and their families received a variety of medical and social work services, but one group of babies (the “experimentals”) went into a day care

program. The program started when the babies were just over a month old, and it provided care for six to eight hours a day, five days a week, fifty weeks a year, emphasizing cognitive enrichment activities with teacher-to-child ratios of one to three for infants and one to four to one to six in later years, until the children reached the age of 5. It also included enriched nutrition and medical attention until the infants were 18 months old.

69

The Abecedarian Project is the apotheosis of the day care approach. This is extremely useful from a methodological perspective: Even if the nation cannot afford to supply the same services to the entire national population of children who qualified for the Abecedarian Project, it serves as a way of defining the outer limit of what day care can accomplish given the current state of the art.