The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (132 page)

Read The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life Online

Authors: Richard J. Herrnstein,Charles A. Murray

Tags: #History, #Science, #General, #Psychology, #Sociology, #Genetics & Genomics, #Life Sciences, #Social Science, #Educational Psychology, #Intelligence Levels - United States, #Nature and Nurture, #United States, #Education, #Political Science, #Intelligence Levels - Social Aspects - United States, #Intellect, #Intelligence Levels

34

The remaining possibility is that the increase in the SAT pool during the 1980s brought students into the pool who could score 700 but had not been taking the test before. This possibility is not subject to examination. It must be set against the evidence that extremely high proportions of the top students have been going to college since the early 1960s and that the best-of-the-best, represented by those who score more than 700 on the SAT, have been avidly seeking, and being sought by, elite colleges since the 1950s, which means that they have been taking the SAT. Note also that the proportion of SAT students who identify themselves as being in the top tenth of their high school class—where 700 scorers are almost certain to be—was virtually unchanged from 1981 to 1992. Finally, if highly talented new students were being drawn from some mysterious source, why did we see no improvement on the SAT-Verbal? It seems unlikely that the increase in the overall proportion of high school students taking the SAT can account for more than a small proportion, if any, of the remarkable improvement in Math scores among the most gifted during the 1980s.

35

Once again, the changes are not caused by changes in the ethnic composition of the pool (for example, by an influx of test takers who do not speak English as their native language). The trendline for whites since 1980 parallels that for the entire test population.

36

National Center for Education Statistics 1992, p. 57. We also examined the SAT achievement test results. They are harder to interpret than the

SATs because the test is regularly rescaled as the population of students taking the test changes. For a description of the equating and rescaling procedures used for the achievement tests, see Donlon 1984, pp. 21-27. The effects of these rescalings, which are too complex to describe here, are substantial. For example the average student who took the Biology achievement test in 1976 had an SAT-Math score that was 71 points above the national mean; by 1992, that gap had increased to 126 points. The same phenomenon has occurred with most of the other achievement tests (Math II, the more advanced of the two math achievement tests, is an exception). Put roughly, the students who take them are increasingly unrepresentative of the college-bound seniors who take the SAT, let alone of the national population. We focused on the students scoring 700 or higher by again assuming that since the 1960s, a very high proportion of the nation’s students who could score higher than 700 on any given achievement test took the test. We examined trends on the English Composition, American History, Biology, and Math II tests from three perspectives: the students scoring above 700 as a proportion of (1) all students who took that achievement test; (2) all students who took the SAT; and (3) all 17-year-olds. Method 1 (as a proportion of students taking the achievement test) revealed flat trendlines—not surprisingly, given the nature of the rescaling. Methods 2 and 3 revealed similar patterns. With all the reservations appropriate to this way of examining what has happened, we find that the proportion scoring above 700 on English Composition and Math II mirrored the contrast we showed for Verbal and Math scores on the SAT: a sharp drop in the English Composition in the 1970s, with no recovery in the 1980s; an equally sharp and steep rise in the Math II scores beginning in the 1980s and continuing through the 1992 test. The results for American History and Biology were much flatter. Method 2 showed no consistent trend up or down, and only minor movement in either direction at any time. Method 3 showed similar shallow bowl-shaped curves: reductions during the 1970s, recovery during the 1980s that brought the American History results close to the first year of 1972, and brought Biology to a new high, although one that was only fractionally higher than the 1972 results. This is consistent with a broad theme that the sciences and math improved more in the 1980s than the humanities and social sciences did.

37

Diane Ravitch’s account, one of the first, is still the best (Ravitch 1983), with Finn 1991; Sowell 1992; Ravitch 1985; Boyer 1983; and Porter 1990 providing perspectives on different pieces of the puzzle and guidance to the voluminous literature in magazines and journals regarding the educational changes in elementary and secondary schools. For basic texts by advocates of the reforms, see Goodman 1962; Kohl 1967; Silberman 1970; Kozol

1967; Featherstone 1971; Illich 1970; and the one that in some respects started it all, Neill 1960.

38

Fiske 1984; Gionfriddo 1985.

39

Sowell 1992, p. 7.

40

Bishop 1993b.

41

Bejar and Blew 1981; Breland 1976; Etzioni 1975; Walsh 1979.

42

By the early 1980s, when the worst of the educational crisis had already passed, the High School and Beyond survey found that students averaged only three and a half hours per week on homework (Bishop 1993b).

43

DES

1992b, Table 132.

44

DES

1992b, Table 129. The picture is not unambiguous, however. Measured in “Carnegie units,” representing one credit for the completion of a one-hour, one-year course, high school graduates were still getting a smaller proportion of their education from academic units than from vocational or “personal” units (National Center for Education Statistics 1992, p. 69).

45

We do not exempt colleges altogether, but there are far more exceptions to the corruption as we mean it at the university level than at the high school level, in large part because high schools are so much more shaped by a few standardized textbooks.

46

Gionfriddo 1985.

47

Irwin 1992, Table 1. The programs we designated as for the disadvantaged were the Title I basic and concentration grants, Even Start, the programs for migratory children, handicapped children, neglected and delinquent children, the rural technical assistance centers, the state block grants, inexpensive book distribution, the Ellender fellowships, emergency immigrant education, the Title V (drug and alcohol abuse) state grants, national programs, and emergency grants, Title VI (dropout), and bilingual program grants.

48

DES

1992b, Table 347.

49

Calvin Lockridge, quoted in “Old debate haunts Banneker’s future,”

Washington Post,

March 29, 1993, p. A10.

50

Ibid.

51

Bishop 1993b.

52

For a coherent and attractive list of such reforms, see Bishop 1990b.

53

Stevenson et al. 1990.

54

E.g., 63 percent of respondents in a recent poll conducted by Mellman-Lazarus-Lake for the American Association of School Administrators thought that the nation’s schools needed “major reform,” compared to only 33 percent who thought their neighborhood schools needed major reform. Roper Organization 1993.

55

E.g., Powell, Farrar, and Cohen 1985.

56

Bishop has developed these arguments in several studies: Bishop 1988b, 1990a, 1990b, 1993a, 1993b.

57

Bishop 1993b (p. 20) cites the example of Nationwide Insurance, which in the single year of 1982 sent out over 1,200 requests for high school transcripts and got 93 responses.

58

Bishop 1988a, 1988b, 1990a, 1993a, 1993b.

59

Bishop 1990b.

60

Ibid.

61

The Wonderlic Personnel Test fits this description. For a description, see E. F. Wonderlic & Associates 1983. The value of a high school transcript applies mainly to recent high school graduates who have never held a job, so that employers can get a sense of whether this person is likely to come to work every day, on time. But after the first job, it is the job reference that will count, not what the student did in high school.

62

The purposes of such a program are primarily to put the federal government four-square on the side of academic excellence. It would not appreciably increase the number of high-scoring students going to college. Almost all of them already go. But one positive side effect would be to ease the financial burden on many middle-class and lower-middle-class parents who are too rich to qualify for most scholarships and too poor to send their children to private colleges.

1

Quotas as such were ruled illegal by the Supreme Court in the famous Bakke case.

2

Except as otherwise noted, our account is taken from Maguire, 1992.

3

A. Pierce et al., “Degrees of success,”

Washington Post,

May 8, 1991, p. A31.

4

Seven COFHE schools provided data on applicants and admitted students, but not on matriculated students. Those schools were Barnard, Bryn Mawr, Carleton, Mount Holyoke, Pomona, and Smith. The ethnic differences in scores of admitted students for these schools were in the same range as the differences for the schools shown in the figure on page 452. Yale did not supply any data by ethnicity. Data are taken from Consortium on Financing Higher Education 1992, Appendix D.

5

“Best Colleges,”

U.S. News & World Report,

Oct. 4, 1993, pp. 107-27.

6

Data for the University of Virginia and University of California at Berkeley are for 1988 and were obtained from Sarich 1990 and L. Feinberg, “Black freshman enrollment rises 46% at U-Va,”

Washington Post,

December 26, 1988, p. C1.

7

The figures for standard deviations and percentiles are based on the

COFHE schools, omitting Virginia and Berkeley. The COFHE Redbook provides the SAT scores for the mean, 25th percentile, and 75th percentile by school. We computed the estimated standard deviation for the combined SATs as follows:

Estimated standard deviation for each test (Verbal and Math): given the scores for the mean and any percentile, the corresponding SD is given by (x−m)/z, where

x

is the score for the percentile,

m

is the mean, and

z

is the standardized score for that percentile in a normal distribution. Two separate estimates were computed for each school, based on the 25th and 75th percentiles. These two estimates were averaged to reach the estimated standard deviation for each test.

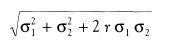

The formula for estimating the standard deviation of combined tests is , where

, where

r

is the correlation between the two tests and represents the standard deviation of the two tests. The correlation of the verbal and math SATs as administered to the entire SAT population is .67 (Donlon 1984, p. 55). The correlation for elite schools is much smaller. For purposes of this exercise, we err on the conservative side by continuing to use the correlation of .67. We further err on the safe side by using the standard deviation for the entire student population, which is inflated by the very affirmative action admissions that we are analyzing. If instead we were to use the more appropriate baseline measure, the standard deviation for the white students, the Harvard standard deviation (known from unpublished data provided by the Admissions Office) would be 105 instead of 122. For both reasons, the analysis of the gap between minority and white students in the COFHE data is understated. To give an idea of the magnitude, our procedure underestimated the known black-white gap at Harvard by 14 percent.

8

The Berkeley figure for Latinos is an unweighted average of Chicanos and other Latino means.

9

Scholars who have tried to do work in this area have had a tough time obtaining data, up to and including researchers from the Office for Civil Rights in the Department of Education (Chun and Zalokar 1992, note, p. 108).

10

The Berkeley figure for Latinos is an unweighted average of Chicanos and other Latino means. For Davis, only a Chicano category is broken out. Virginia had no figure for Latino students.

11

Chun and Zalokar 1992.

12

Committee on Minority Affairs 1984, p. 2.

13

Chan and Wang 1991; Hsia 1988; Li 1988; Takagi 1990; Bunzel and Au 1987.

14

K. Gewertz, “Acceptance rate increases to 76% for class of 1996,”

Harvard University Gazette,

May 15, 1992, p. 1.

15

F. Butterfield, “Colleges luring black students with incentives,”

New York Times,

Feb. 28, 1993, p. 1

16

For Chicano and other Latino students at Berkeley, the comparative position with whites also got worse. SAT scores did not rise significantly for Latino students during the 1978-1988 period, and the net gap increased from 165 to 254 points for the Chicanos and from 117 points to 214 points for other Latinos.