The Battle for Gotham (27 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

These were direct impacts. No way exists to measure the ripple effects of the lost businesses, residences, and institutions near the newly formed gaping hole. It is safe to say, however, that once the undermining began in one area, fraying of the larger surrounding fabric took on its own momentum.

Gay Talese described how a big project’s clearance spreads deterioration beyond the specific cleared site. In a 1964

New York Times

story about the massive dislocation impacts in Bay Ridge following the demolition of five hundred homes and the dispossessing of seven thousand people for the expressway leading to the new Verrazano Bridge, Talese wrote:

In all, it took 18 months to move out the 7,000 people. Eventually, even the most stubborn—or out-of-touch residents of Bay Ridge abandoned their homes because of resignation or fear—fear of being alone in a spooky neighborhood; fear of the bands of young vagrants who occasionally would roam the area smashing windows or stealing doors, picket fences, light fixtures or shrubbery; fear of the derelicts who would sleep in empty apartments or hallways; fear of the rats that people said would soon be crawling up from the shattered sinks and sewers because, it was explained, “rats also are being dispossessed from Bay Ridge.”

14

The federal official in charge of the program in the early years told Caro, “Because Robert Moses was so far ahead of anyone else in the country, he had great influence on urban renewal in the United States—on how the program developed and on how it was received by the public—more than any other single person.”

Urban renewal became a favorite of mayors across the country because of the lava flow of federal funds that came with it, especially if coupled with a highway project. Few cities resisted like Savannah, where, a local resident reports, “it was resisted as a communist plot.” Where the demolition derby got started, it was hard to stop. Each massive project inevitably led to further decay and an accelerated cycle of clearance. The holes in the urban fabric of American cities are still visible today from Buffalo to Cleveland to St. Louis and beyond.

Title I was, indeed, producing middle-income housing, as progressive Democrats, Regional Plan advocates, the press, and all Moses’s supporters wanted. Between June 29 and July 2, 1959, the

New York Times

published a series of articles, “Our Changing City,” surveying the state of public housing and urban renewal. Barren looking, devoid of hope, and overwhelmed with relocation problems are how the articles found public housing. Ford Foundation staffers “became convinced that Title I had aggravated the city’s housing shortage, destroyed many Old Law tenements that could have sheltered low-income residents, and created sterile, crime-ridden environments.”

15

Deborah Wallace and Rodrick Wallace wrote a very important book,

A Plague on Your Houses: How New York Was Burned Down and National Public Health Crumbled

, that shows the enormous impact all this dislocation had on the mental and public health of the distressed population and the entire city and region. They wrote:

Many poor neighborhoods simply collapsed from the spatial concentration and temporal peaking of these modes of housing destruction. Health areas of the South-Central Bronx, for example, lost 80 per cent of both housing units and population between 1920 and 1980. About 1.3 million white people left New York as conditions deteriorated from housing overcrowding and social disruption. About 0.6 million poor people were displaced and had to move as their homes were destroyed. A total of almost two million people were uprooted, over 10 percent of the population of the entire Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (25 counties).

Just thinking about the magnitude of this forced migration helps focus on why, by the 1960s and ’70s, New York was a collapsing mess. As Moses said, it was the “meat ax” approach to city building.

THE HUMAN TOLL

What is not recognized sufficiently in regards to any of Moses’s cataclysmic urban development schemes is exactly what the Wallaces were referring to: the thousands upon thousands of lives disrupted, the downward spiral of so many lives often jump-started by such massive demolition projects, the endless tales of social dislocation. The Wallaces have provided additional insights not often discussed.

Based on years of study, they document how the fires of the 1970s continued to destroy what Urban Renewal started. What they shockingly outline is that this occurred within a framework of deliberate city policies that were based on erroneous information, pseudoscience, manipulated data, and malevolent policy goals.

16

The Wallaces effectively show that the closing of firehouses, guaranteeing inadequate responses, and the withdrawal of other municipal services in the most vulnerable neighborhoods purposefully continued the clearance that Moses started.

17

This all occurred under the post-Urban Renewal policy of “Planned Shrinkage” with the overt goal of killing off “sick” neighborhoods.

18

What was often destroyed, the Wallaces note, were, in fact, “stable ‘slums,’ i.e. poor neighborhoods of old, mildly overcrowded housing that are not experiencing rapid deterioration physically or socially, are true communities, often with a history decades long.” They then quote a 1977 book on public health and the built environment by Loren Hinkle, published by the Centers for Disease Control. It goes to the heart of the issue: “It is the social environment and not the physical environment which is the primary determinant of the health and well-being of people who live in cities. . . . The importance of the social milieu is such that the dislocation and disruption of social relations that are produced when one moves a family from a dilapidated dwelling [within a functioning community] to a modern apartment [outside that community] may have adverse effects upon health and behavior that are not offset by the clean, comfortable, and convenient new dwelling.”

19

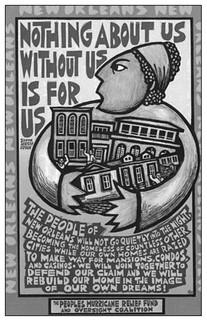

5.1 Ricardo Levins Morales designed this poster in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina for the people left out of the rebuilding planning process in New Orleans. He could just as well have designed it for the people of New York City left out of Robert Moses’s construction process. (To view it in splendid color, visit his website

www.rlmarts.com

.)

Such a massive scale of social disruption would not have occurred if organic change and a different scale and form of progress had been allowed to take hold—the kind that Jane Jacobs identified as building up the fertility of the land instead of eroding it. So many dismembered lives could have been uplifted instead of undermined, given a different path of development. Voices advocating that alternative path were drowned out by Moses and stilled by the deaf ear of a press and the policy-making community enthralled with his message and accomplishments. Projects on the scale that Moses built inevitably and severely and destructively disrupt the social, economic, and psychological life of thousands. Destabilization is a given. The benefits cannot match the losses.

LEARNING BY LISTENING

Jacobs’s views about city development evolved. As noted in the introduction, she first learned in East Harlem how the delicate urban fabric worked to stabilize neighborhoods. By visiting the area, walking the streets, and talking to residents, she learned how the row houses, small apartment houses, tenements, stores, and local businesses created an intricate web, the whole of which gained strength from the complex, often invisible connection of the parts. Through the eyes of Union Settlement House director and Episcopal minister William Kirk and social worker Ellen Lurie, she also watched it being torn apart by one public housing project after another, wiping out an estimated tens of thousands of dwellings and 1,500 businesses.

Moses plowed through the South Bronx to build the seven-mile Cross Bronx Expressway, connecting the George Washington Bridge to I-95, as Caro vividly details.

20

In just one mile, 1,530 families (more than 60,000 people) and businesses were dislocated and 159 buildings demolished.

21

This occurred despite the existence of an alternate route a few blocks away that would have been quicker and cheaper. Only six tenements and nineteen families were in the way of the alternate route. Moses dismissed the thousands of Bronx residents and businesses pleading for the alternate route to save their homes, livelihoods, and community, saying only, “It was a political thing that stirred up the animals there.” Residents and businesses were given ninety days to leave. Like so many other wiped-out neighborhoods, it had solid schools with involved parents, local businesses, seven movie houses, synagogues, churches, old walk-ups with affordable apartments that had light and air, and all manner of social institutions and networks.

And what do we have there now? A traffic nightmare with four of the eleven worst bottlenecks in the country. Nineteen of the country’s fifty worst bottlenecks are either in the five boroughs or in nearby counties, as Tom Namako reported in the

New York Post

on February 26, 2009. On September 20, 2002, Alan Feuer in the

New York Times

described the truck-clogged, congested road as “arguably the most savage road in New York City.”

THE HUMAN TOLL

What is seldom mentioned in regards to any of Moses’s cataclysmic urban development schemes is the thousands of lives disrupted. Caro’s chapter “One Mile” recounts how this devastation undermined the South Bronx and is famously cited for detailing the resulting human pain and suffering. Rare is any similar examination of the human costs of other such disruptive projects. Moses and his public relations machine, along with the political leaders, did such a good job of selling the public on the false notion that these strategies cleaned up “slums,” cleared “blight,” and replaced “deteriorated” neighborhoods that most people today are unaware of the true condition and quality of these communities and the lives of the people in them.

The true mark of Robert Moses has to be the way he treated the people who stood in his way. Elizabeth Yampierre, a Brooklyn lawyer and citywide leader of the city’s environmental justice movement, recalls:

My family lived on the Upper West Side, in a blue-collar community. We had a family infrastructure that made it possible for the women in my family to work, for the children to be cared for, and although we were not wealthy by any means, we were doing okay. When we were displaced, we became “roadkill” in Robert Moses’ vision. Our family was scattered to the Bronx to Queens and throughout Manhattan. I went to five schools in eight years, and, in my family, some people went on to become drug addicts and some women went on public assistance. The entire fabric of my family was destroyed as a result of that displacement.

Yampierre told her story at a public celebration of Jane Jacobs’s life held in Washington Park after Jacobs’s death in 2006. Yampierre had not read Jacobs’s books.

A similar human tragedy unfolded in South Brooklyn when Moses ignored the pleas of residents of Park Slope and Windsor Terrace to move the Brooklyn/Queens Expressway to avoid razing five hundred buildings, mostly homes. An alternate route, again only a few blocks away, would use mostly vacant lots and “save money and heartache,” the

Brooklyn Eagle

newspaper reported in March 1945. Even the state legislature unanimously voted a resolution asking for relocation since the road was partially state funded. He ignored them all.

Moses became known as the country’s foremost “master builder,” an American Baron Haussmann, the man who shaped nineteenth-century Paris. But Moses didn’t start out in that direction.

A REFORMER TO START

Moses started out as an advocate of government reform and rose to power under Governor Alfred E. Smith, who in 1919 assigned him the task of reorganizing state government, heavily centralizing it and shifting considerable power from the legislature to the governor. As Moses filled an assortment of appointments, he learned how to navigate that governmental power better than anyone. He didn’t override the political system; he used it. With each agency and authority he created and then took over, he began building, first with the Long Island Park Commission, then the New York City Parks Department, the New York State Power Commission, and eventually twelve state and city positions at one time.

The concept of the public authority—an independent agency separated from normal government process of checks and balances and with the ability to issue its own revenue bonds—was Moses’s. Proceedings are secret, and records are not public. Authorities were purposely designed to be impervious and impregnable to outside voices and impacts. The public authority, Caro notes, “became the force through which he shaped New York and its suburbs in the image he personally conceived.” To this day, the public authority remains a favorite government device “to get things done” and to avoid a genuine public process that includes community input, real negotiation, and compromise.