The Attacking Ocean (22 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Over hundreds of years, the Yangtze Valley became a cockpit of competing states and chiefdoms until the first emperor, Qin Shi Huangdi, unified China in 221 B.C.E. The succeeding Han dynasty, which flourished from 206 B.C.E. to 220 C.E., brought great economic prosperity and fostered stable, highly productive irrigation agriculture, which endured into historic times. A wealthy and sophisticated imperial realm developed, to be sure, but one plagued by severe floods and droughts resulting from monsoon failures that killed tens of thousands.

LIFE ALONG THE Lower Yangtze was a constant adjustment to the realities of life very close to sea level. In time, high levees protected much of the surrounding countryside from the flooding river. But when these levees broke, water swept across the surrounding landscape, bringing death and disease in its train. The delta was home to small communities of rice farmers, who had more problems with river floods than with sea levels during the imperial centuries. Their difficulties with the ocean came from sea surges generated by typhoons, but these were temporary episodes, expensive in terms of destruction and human life without question, but not a permanent encroachment on land they had farmed for many generations.

There were some towns and small cities, notable among them a market town, now named Shanghai, founded as early as the tenth century C.E. in a swampy area east of Suzhou in the delta.

9

Shanghai prospered modestly before becoming a major center of cotton production and textile milling of all kinds. Silk from the Suzhou region became famous throughout China, creating a class of wealthy estate owners. These industries remained the mainstay of the Shanghai economy until the nineteenth century. The First Opium War (1839–1842) between Britain and China

ended with the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, which created five treaty ports for international trade. One of them was Shanghai, whose close proximity to the mouth of the Yangtze made it an ideal location for an explosion of trading activity.

Shanghai soon became a boom city. By the 1860s, the city boasted of a significant population of British and American merchants, who formed an international settlement centered on the waterfront area still known as the Bund. Three quarters of a century later, three million people lived in the city, now one of the largest in the world. Thirty-five thousand foreigners, Shanghailanders, controlled half of Shanghai, now the commercial center of Asia. The Japanese occupation of World War II brought the boom to a halt. Nor did the city prosper under early Communist rule, when it bore a heavy tax burden. Everything changed during the 1990s, when Shanghai-born politicians achieved some dominance in the central government. Since then, the city has been a commercial powerhouse, handling over a quarter of the trade passing through Chinese ports, an economic boom with potentially disastrous environmental consequences.

10

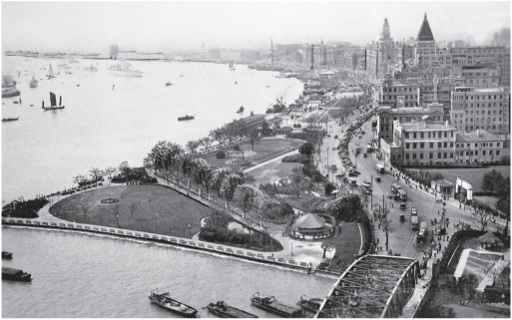

Figure 9.3

Shanghai’s Bund in about 1935. © Albert Harlingue/Roger-Viollet/The Image Works.

Today, over twenty-three million people live in the city and its environs, the population growth caused not by the birth rate, which is lower than that of New York, but by continual in-migration from people seeking work and opportunity. The administrative area of the city includes significant agricultural land, but construction proceeds at an astounding level, much of it fueled by government investment. Population growth, exploding industrial activity, and many more motor vehicles have created serious and in some respects unexpected environmental problems that not only place the low-lying city at serious risk from water pollution and solid-waste issues, but also, most important, from sea level rise.

Shanghai lies on the East China coastal plain, the city and its environs located on an alluvial flatland that forms a bulge of the Yangtze delta, averaging about 4 meters above the low tide mark. Since high tides can occasionally reach 5.5 meters, the city already relies on dikes and embankments to prevent flooding—this before one factors in rising sea levels. Until the construction of the Three Gorges Dam far upstream, the Yangtze generated a huge runoff of freshwater each flood season, delivering about 486 million metric tons of silt to its estuaries every year. The sediment formed submerged deltas and tidelands that gradually formed land ever farther out to sea, despite rising sea levels.

11

Like deltas everywhere, that of the Yangtze is subsiding every year. Until recently, the subsidence has always been due to natural tectonic forces. From 1921 through 1948, land subsidence in Shanghai was 2.4 centimeters a year. As industrial activity picked up after 1949, ground-water extraction accelerated dramatically. The underlying sediment became compacted and subsidence increased rapidly. By 1965, the cumulative effects formed two large depressions that covered more than four hundred square kilometers, the subsidence level reaching 2.63 meters, despite efforts to reduce groundwater pumping. At this point, fifty square kilometers of the city along the Huangpu River were below normal high tide level. Despite artificial groundwater replenishment, reduced pumping, and adjusted pumping layers, measures that are said to have brought the subsidence under control, the land surface continues to sink at a rate of 4 millimeters annually in the city, even more in suburban

industrial districts, where pumping still exceeds replenishment by 30 percent or more.

12

Ground subsidence obviously contributes to Shanghai’s vulnerability to rising sea levels. Flood defenses along the Huangpu River and in Suzhou Creek, major port areas, have already been raised several times, but they are still inadequate protection. The construction of floodgates and raising the existing flood walls even farther will require enormous financial investment on the part of the city.

HERE, AS ELSEWHERE in the world, significant sea level rise resumed after the mid-nineteenth century. According to official Chinese records, sea level rise along the East China Sea coast has averaged between 14 and 19 centimeters over the past century. A rise of about 2 to 3 millimeters a year is predicted for the foreseeable future. After correction for vertical movements caused by subsidence and earth movements, the average rise is about 2 millimeters annually. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has produced estimates of 18 centimeters by 2030 and 66 centimeters in 2100. The highest estimate is 110 centimeters. All these projections assume what is called business as usual—no efforts to curb greenhouse gases. However, it is hard to estimate sea level trends in the Yangtze delta, because of river runoff, the constant shifts in river channels, and land subsidence caused by pumping out groundwater. Expert calculations using tidal gauges and other data are in the 2.6 centimeter range. As far as one can discern, the rate of sea level rise in the delta is somewhat higher than elsewhere along the coast, perhaps because of river runoff, but everywhere, the trend is toward ever-higher levels.

Sea level rise in the Shanghai city area itself during the twentieth century has exceeded two meters, which represents a significant threat to the city and surrounding coastal plains. Now that the Three Gorges Dam on the Middle Yangtze has significantly reduced sediment discharge from upstream, the menace of accelerated coastal erosion also raises its ugly head.

13

(Fortunately, tributary rivers still bring down large sediment loads.) River runoff and shifting river channels are the major source of

erosion, for they cut back the low-lying coast and narrow, or completely remove, tidal flats that are valuable coastal protection. Nearly half the coastline in the Shanghai municipality is described as “eroding,” so much depends on the silt loads that arrive from upstream. If there is not enough sediment in future decades, rising water levels will decimate tidal flats and intensify erosion throughout the estuary. Widespread land reclamation and clearance of mangroves and marshes for agriculture and development add to the threat.

Subsidence, in part due to headlong development, especially the construction of high-rise buildings, means that much of Shanghai is only 1.5 meters above low tide level. In 1999, existing dikes and flood walls protecting the city extended 465 kilometers, with an average height of eight to nine meters, designed to withstand a Force 10 typhoon and a fifty-year high tide. They are currently being upgraded to withstand a thousand-year flood, but standards in the surrounding agricultural regions are still poor. Without such defenses, almost all of the city and surrounding districts would be flooded with every high tide. A half-meter rise in sea levels would inundate 855 square kilometers of the city, port, and environs. Nearly all the city would disappear underwater if the level rose by a meter. At the same time, sea level rise would aggravate the salinization of the soil and increase chronic waterlogging of low-lying agricultural land. The Pudong area with its major industrial facilities would lie below the water with a sea level rise of a half meter or slightly more. The only response short of the impossible task of moving the entire city is to raise and consolidate the existing coastal dikes and flood walls to prevent catastrophic inundation.

Then there are the effects of sea surges generated by typhoons and major gales. About two typhoons hit Shanghai each year; the highest sea surge on record reached 5.22 meters near the city center in 1981. A combination of sea level rises and a predicted higher frequency of typhoons in the future may, theoretically, have the effect of reducing the thousand-year flood frequency to a century or even less. Furthermore, heavy rains after typhoons and other major storms result in high flood levels upstream, which cause extensive waterlogging in the delta area.

High sea levels would also reduce the amount of runoff that can be handled naturally by gravity, so expensive pumping may be necessary.

Overpumping groundwater to supply cities and nourish irrigated fields as well as promiscuous construction in coastal cities like Shanghai has exacerbated the process, causing sediments to compact and sea levels to rise sharply. The faster-rising ocean of the immediate future will deepen the continental shelf close offshore and make it harder for waves to disperse coastal sediment. River gradients will become shallower, as they have elsewhere, decreasing sediment discharge. So will human activity upstream, like the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, which has reduced sediment discharge even further. Already coastal sand barriers are retreating; sediment is reduced, so beach erosion increases, especially with prolonged La Niña conditions and a predicted higher incidence of severe storms and their accompanying sea surges. As the sea level rises, so the coastline retreats, triggering significant environmental changes farther inland. Saltwater intrusion intensifies and freshwater supplies for towns and villages are affected, especially during the dry season. Between December and March, when water levels are lower, the authorities already restrict water supplies from the heavily polluted Huangpu River that flows through the city. Future sea level rises may seriously affect water quality in Shanghai at a time when local aquifers are already well drawn down, but fortunately not yet affected by seawater. The government is taking urgent steps to replenish groundwater not only in the Shanghai region but also elsewhere, but this will be effective only if strict controls govern the quality of the replenishment supplies, something that has been erratic in the past.

Almost half of Shanghai’s coastal zones have been reclaimed from marshes and tidal flats, this for an area that produces about a ninth of all China’s agricultural and industrial output, with but I percent of the national population. Shanghai is the most densely occupied city in China, but most of its more than twenty million already live below the high tide mark—or would do so if the ocean rose by a half meter. The situation is somewhat akin to that in Bangladesh, with the long-term prospect of millions of people becoming environmental refugees. The cost of

resettlement would be almost unimaginable, leaving effectively only one option—huge capital expenditure on flood defenses. The future depends on effective long-term planning of all construction in areas subject to erosion and potential inundation, strengthening of seawalls, and systematic experiments with salt-resistant crops while accelerating land reclamation from marshes and tidal flats to tap the potential of foreshore areas as quickly as possible. A range of other measures might also be effective. One option might be to construct freshwater reservoirs upstream to receive floodwaters, which could then be released during the dry season. But here again there are environmental consequences, for a reduced flood downstream would also mean less sediment deposition, which would not be so bountiful if the flow came from controlled reservoir releases.

All of this requires closely integrated, even authoritarian, planning and proactive construction of sea defenses and other facilities against the day when sea levels will be effectively higher than Shanghai. An expensive era of very long-term planning and massive capital expenditure for a future beyond the lifetimes of those currently living and working

in Shanghai may yield few immediate benefits in today’s world. But future generations will bless the foresight that protected one of the great cities of the world from inundation.