The Attacking Ocean (18 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

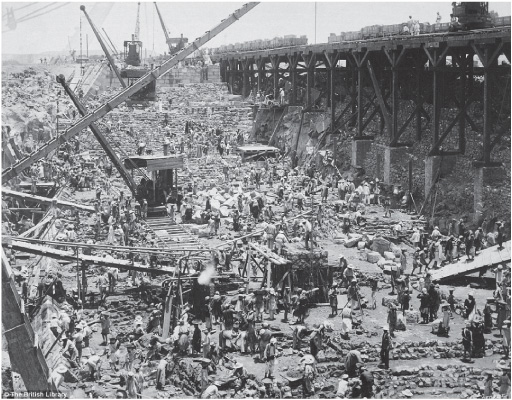

Figure 7.2

Constructing the first Aswan Dam around 1899. D. S. George/British Library.

Even the construction of the Aswan Low Dam affected the distant coastline, for reduced silt levels removed some of the natural barriers to coastal erosion. The High Dam has had much more widespread effects that may even be felt far from the delta, elsewhere in the eastern Mediterranean.

12

Groin and breakwater construction to refresh beach sand along popular beaches has had some beneficial results, but the long-term effects are impossible to discern. There are other problems as well. With many fewer nutrients carried to the coast, both lagoon and in shore marine fisheries are fading rapidly. Sardines off the delta depended heavily on phytoplankton during the flood season. Absent the inundation, the Egyptian sardine fishery declined from about eighteen thousand tons in 1960 to around six hundred tons in 1969, even less today. Stocks have now recovered considerably, largely because of winter outflows from coastal lakes, but there are signs that sardine migration

patterns have changed. Water hyacinths are clogging waterways and canals, increasing water loss through evaporation and transpiration (loss of water vapor from plants).

Quite apart from the ecological damage, escalating demands for water for industrial, urban, and agricultural purposes upstream of the delta mean that less and less of the Nile reaches the northern reaches behind the shoreline. Much of what does is polluted by industrial waste, municipal wastewater, and runoff from fields treated with heavy doses of chemical fertilizer. The polluted water flows into already shrinking coastal lagoons, threatening fisheries and waterfowl habitats.

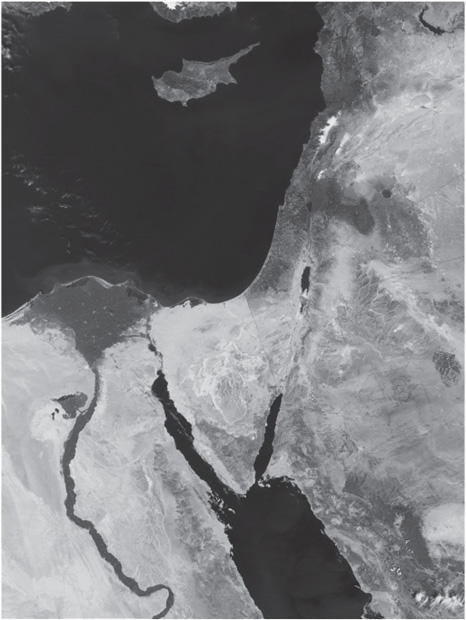

All this is before one factors in population growth and inexorable sea level rises associated with global warming. Egypt’s population is expected to exceed a hundred million people by 2025. Sea levels will rise by at least a millimeter a year into the foreseeable future without accounting for projected climate changes. Combine these sea level figures with estimates of the effects of natural land subsidence, commonplace, as we have seen, in the eastern Mediterranean, and the forecasts are even more depressing. Sophisticated computer models project a relative rise of sea level of between about 12.5 centimeters to an extreme of 30 centimeters in the northeastern delta. These are by no means vast rises in vertical terms, but they are potentially catastrophic horizontally across the northern delta, where the relief varies by little more than a meter. An estimated two hundred square kilometers of agricultural land will vanish under the ocean by 2025, at a time when the rural population density of the delta is rising rapidly.

At present, the Mediterranean is winning the long standoff between land and sea. More sediment now leaves the delta than arrives there. As a result, the ocean will cut back the shore vigorously, even at points of resistance like promontories. Sand washed ashore by storms will infill coastal lagoons. Constantly shifting dunes will form in many places, which will be hard to stabilize by any form of artificial protection. Coastal sand barriers will migrate inland, filling the remaining coastal lagoons, which are already subdivided by expanded irrigation work, roads, and other modern industrial infrastructure. As marshes and swamps disappear, already decimated reserves for migrating birds and

waterfowl will vanish. By 2025, inexorable pumping will encourage the inland migration of saltwater-laden groundwater at a time when more and more land is being diverted from agriculture to urban and industrial use.

Figure 7.3

The Nile River valley and delta from space, an image taken on September 13, 2008, with MODIS, NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer aboard the Aqua satellite. Courtesy: NASA.

The delta has ceased to function as a balanced system. What can be done to solve these daunting problems of land shortage, groundwater pollution, and environmental degradation resulting from an exploding population and increasingly scarce water supplies? In many respects, the Nile delta is akin to the Netherlands, a land trapped between a rising ocean and the land. Egypt does not have the financial resources to embark on a massive coast protection project like those along the North Sea. Nor are there the funds to construct the artificial wetlands and treatment facilities for recycling wastewater—or regenerating mangrove swamps to protect the coast. To restrict and control the increasingly limited waters of the Nile will require strong political will, and also an infrastructure and mechanisms for ensuring fair shares for all, from individuals to industry and agriculture. The stakes are literally life and death. One estimate has it that food shortages resulting from environmental degradation and rising sea levels will trigger massive famines that could turn more than seven million people in Egypt into climate refugees by the end of the twenty-first century–and that figure is conservative. Herodotus was right when he wrote that the Egyptians would suffer if the Nile flood dried up, for drying up it is just as sea levels rise inexorably.

8

“The Whole Is Now One Festering Mess”

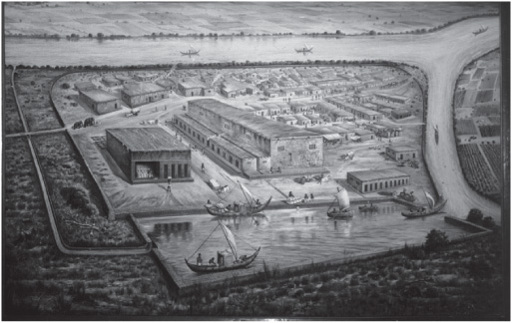

Lothal, Gujarat, India, 2100 B.C.E. The rectangular dockyard bakes under the summer sun. Densely packed cargo ships with battered, sewn planked hulls lie cheek by jowl alongside the quays. Sweating laborers in white loincloths heft bundles of cotton over narrow gangplanks and toss them into empty holds. The tide is high, so the lock gates are open. A heavily laden vessel moves slowly into the narrow defile, her crew straining against long poles. She clears the lock; the stone gate closes. The steersman catches the first of the ebb with his oar and pilots his clumsy charge toward the open sea. High above the port, white figures gaze down from the mud-brick citadel that broods over the bustling harbor.

LOTHAL, EIGHTY KILOMETERS southwest of the modern city of Ahmadabad, was an important, almost unique port on the western Indian coast three thousand years ago.

1

Its anonymous rulers, their names lost to history, commanded the navigable estuaries of the Sabarmati and Bhogavo Rivers where they emptied into the narrow Gulf of Khambhat (Cambay). At the time, the ocean was a mere five kilometers from the prosperous city. From Lothal, cargo ships passed far upstream up the two rivers. Stone anchors in the now-dried-up river channels have been unearthed at least fifty kilometers inland. Today, massive silt deposits laid down by river floods and ancient storm surges have isolated Lothal from the ocean with its predictable monsoon winds that once gave it sustenance.

No one knows when farmers first settled at Lothal, but it was at least five thousand years ago, when a small agricultural settlement rose on a low mound on higher ground on a wide alluvial plain protected from river floods by a mud dike. The village gradually became a town and craft center, well known for its stone-bead workshops, and also for lustrous red pottery, made from a glittering micaceous clay. By 2400 B.C.E., the growing town was part of a much larger interconnected world, that of the Harappan civilization, a tapestry of cities, towns, and villages centered on the Indus and Saraswati Rivers to the north.

2

Lothal’s appeal came from the fertile soils in its hinterland, which were ideal for irrigation agriculture and cotton cultivation, the latter an important export to distant lands. The city itself became not only a manufacturing center but also one of the major ports that linked the cities of the Indus Valley to other lands.

The monsoon winds of the Indian Ocean are among the most useful of all prevailing breezes, for they obligingly blow in opposite directions seasonally.

3

The winter brings the gentle northeast monsoon, the summer the more boisterous, less predictable southwesterlies when the west coast of India forms a lee shore and is best avoided. As a result, a ceaseless rhythm of sporadic voyaging developed over the centuries. These were coasting passages that passed from village to village, bay to bay, between the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf and lands perhaps as far away as Southern India’s Malabar Coast, where shipbuilding timber could be found. Cotton, stone beads, fine pottery, and other goods passed east. Gold, silver, copper, and other commodities came from ports in the west, perhaps in modern-day Bahrein. This coasting trade never assumed the dimensions of later long-distance Indian Ocean commerce, for the Indus Valley cities were oriented more toward the land and terrestrial trade networks than to the ocean. Nevertheless, Lothal became the most important port in their world. The mouth of the Indus River to the north ended in an extensive delta of braided channels near Karachi that presented formidable navigational challenges with its shallows. According to an Egyptian-Greek pilot of the first century C.E., “The water is shallow, with shifting sandbanks occurring continually and a great way from the shore.” Numerous sea serpents and “a very great ebb and slow of tides” added to the hazards.

4

At first ships visiting Lothal had to tie up alongside a primitive quay in fast-moving tidal waters. When the rivers overflowed their banks in 2350 B.C.E. and destroyed the town, the port’s leaders transformed the strategic ruined location into an imposing metropolis where the principal buildings stood above flood level on brick platforms. The entire undertaking took years and involved building an artificial dockyard thirty-seven meters long, twenty-two meters wide, and four and a quarter meters deep. An inlet at the northern end with gates connected the dockyard to the Sabarmati River at high tide—the earliest known lock in history. A 260-meter-long wharf on the east side of the dockyard connected it to a huge warehouse built on a platform over three meters above flood level. Beyond the docks lay the upper town, also built on a platform, where the rulers and prominent individuals built imposing houses. A short distance away was the lower town with its workshops, bead makers, and potters. The entire city boasted of an elaborate drainage and sewage system.

For all its thriving export trade, Lothal was never a completely safe port. Two unpredictable forces were in play: river silt and the occasional

tropical cyclone. The city lay on a slightly elevated portion of river floodplain, formed by silt carried downstream by monsoon floods between July and September. Fine silt made for fertile soils; irrigation agriculture worked well for cotton and other groups, except in years when the monsoon rains were exceptionally heavy. Such rainfall tended to arrive in La Niña years in the distant southwestern Pacific Ocean, when the southwestern monsoon was more powerful than usual. Such rains bred catastrophe. Swollen rivers burst their banks. Silt-laden flood-waters submerged villages and destroyed irrigation canals and growing crops. On many occasions, thousands perished both from the inundation and from the famine and epidemics that ensued. The same hazard menaces much of Pakistan and the Lothal region today. In 2010, monsoon floods in the western Punjab and Sindh affected over 570,000 hectares of cropland and inundated a million dwellings. Over two thousand people perished. Another major flood in 2011 left two hundred thousand people near Karachi alone homeless. Such monsoon floods in the past would have had devastating effects far downstream at Lothal, where rapid silt buildup and rushing floodwaters could inundate much of the city.