The Atheist’s Guide to Christmas (19 page)

Read The Atheist’s Guide to Christmas Online

Authors: Robin Harvie

Isn’t it enough to see that a garden is beautiful without having to believe that there are fairies at the bottom of it too?

—D

OUGLAS

A

DAMS

C

HRISTINA

M

ARTIN

Writing is a strange occupation. When you try really hard to think of ideas, you come up totally blank, and when you’re sitting around on your backside procrastinating, inspiration strikes. It really doesn’t do much to encourage any kind of work ethic, I can tell you.

Here’s a case in point. I was having a very unproductive day. None of the ideas I was working on seemed to have legs. As always in these situations, I abandoned what I was doing, made a cup of tea, and went online. I checked my Hotmail account, updated my Facebook status, had a quick glance at Google News . . . and that’s when I saw the headline that started it all off:

Gay Rights Don’t Trump Christian Rights Say Christian Rights Group

What a ridiculous statement,

I thought.

As though people’s rights and beliefs can be reduced to a metaphorical game of Top Trumps . . . Actually, now you come to mention it, that would be quite funny!

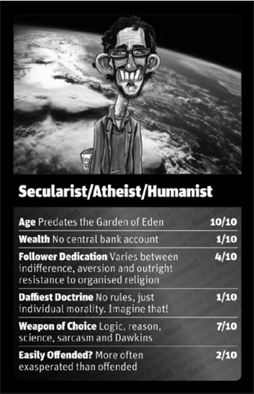

Fast-forward to a couple of months later (November 2008) and God Trumps—a card game that lists and ranks the habits and foibles of the major belief systems, and some minor ones—had been written by me, illustrated by

Guardian

cartoonist Martin Rowson, and published by

New Humanist

magazine.

I filed the issue away in a cupboard along with all my other clippings and thought no more about it.

Until, that is,

New Humanist

posted it on its website in February 2009 and, to quote the cool kids, it went viral. It was being forwarded, favorited, blogged about, and posted on discussion forums at an incredible rate. More than 56,000 people visited the

New Humanist

website the first day God Trumps went online—the average daily visitor count is about 3,000. At the time of writing, God Trumps has had more than 120,000 hits and is still the most viewed article in

New Humanist

’s online history.

This massive online proliferation obviously led to a lot of reaction and debate, and while most people, including religious folk, appreciated the God Trumps for what they are—a comment on the sheer number of belief systems that exist (they can’t all be right!) and the bickering that goes on between them—some people inevitably took them a tad too seriously.

I saw forums containing pages and pages of sober theological debate sparked by the trumps, which is weird when you consider, for example, that the Catholic card has “Popemobile” named as the “Weap

on of Choice.” It’s quite hard to take that seriously, I would have thought, much less have an impassioned debate about it!

There were also conspiracy theories flying about as to why certain religions were excluded. For example, there was no Mormon card in the first set, and one blogger wrote, in delightfully conspiratorial tones, “I think it’s more likely that the Mormons were left out on purpose. Yes, folks, the Mormons are that powerful.” Or perhaps we just didn’t have room? And besides, who’s scared of Mormons?

Anyway, we couldn’t have been that worried about bad reactions. We had the guts to include the famously shady and (allegedly) litigious Scientologists. I’m saying “allegedly” partly as a joke and partly because they really are famously litigious (allegedly). This could go on forever, so I’ll stop now.

Returning to people’s reactions, there was also the person who actually thought the trumps were a genuine set of cards to be used in the process of choosing a religion. No, really. Although maybe that’s not as ridiculous as it sounds—play the game, and whichever faith wins, you take it on. That’s no dafter than just following whatever was foisted on you by your parents, I suppose.

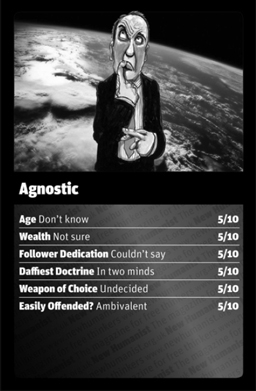

One of my personal favorites out of all the reactions was from the agnostics. They were discussing the trumps on their forum and got really annoyed at their card, which gives them a noncommittal 5/10 in every category. They retaliated by mocking up a sarcastic “atheist” card to get us back, thus replicating in real life the inter-belief bickering that the trumps attempt to lampoon. (And just to digress for a brief moment, what on earth does one discuss all day on an agnostic forum—“I’m still not sure,” “Me neither, I remain completely undecided”? Most odd.)

But returning to the topic at hand, there were quite a lot of people mocking up their own cards. Some of these people were motivated by a desire to see their faith included in the fun and games, others by a sense of dissatisfaction with the original version. One blogger, for example, mocked up an alternative Muslim card, because some considered our version to have been a cop-out. Which leads me neatly to the biggest reaction we received—and yes, it was about Islam. But not in the way you would expect.

Telegraph

blogger and editor of the

Catholic Herald

Damien Thompson wrote an article titled “

Humanist Attack on Religions Chickens Out of Criticising Islam” wherein he accused the piece of not tackling Islam properly for fear of reprisals. Which begs the obvious question: if we were scared of reprisals, why did we include them at all?

I should explain that the Islam card does not have conventional categories like the others. It is instead blanked out and designated as the ultimate trump card on the grounds that nobody is allowed to joke about it.

The irony went over Mr. Thompson’s head, and he used it as an opportunity to knock us for it. In seriousness, all of thi

s surprised me greatly, because when I wrote the piece, although I had expected the Islam card to cause some degree of controversy, I had thought it would be for quite the opposite reason.

The card employs a deliberate (and I would say possibly controversial) stereotype that Muslims are humorless, that they react badly to jokes made at their expense, that they burn effigies over trifling things like cartoons and therefore cannot be treated with the same good-humored approach as everyone else.

In my view I was neither targeting them nor copping out of dealing with them. The fact is that the cards used stereotypes about each faith to comic effect. This was the Muslim stereotype, and at the risk of offending them, as a comedy writer, I had to run with it, because I have more interest in matching the right joke to the right person than in being either politically correct or politically motivated.

Their positioning as the unbeatable trump card also came down to the very mundane fact that I used to play Top Trumps Ghouls and Ghosts as a kid. This game contained an ultimate trump card that had 100 points for every category and was pretty much invincible. As I was modeling my piece on the actual Top Trumps I used to play, I had planned in advance to replicate this feature in my version, for old time’s sake.

What’s more, Islam wasn’t even the front-runner for the title of ultimate trump. I had initially considered the pope as a contender because of his papal infallibility—that must come in extremely handy for someone so often in the wrong—but after some thought I came to the conclusion that, certainly in the current climate, it was more suited to Islam.

My real thought process couldn’t have been further away from the false motives that were being assigned to me—cowardice, hedging my bets, fudging the issue. But what surprised me even more than this gross misunderstanding of my methods was the total lack of humor displayed by not only Mr. Thompson but the many people who shared his view.

The gag on its own was patently obvious, and was further elucidated by some very clear signposting, such as the illustration—a mad mullah—and the very pointed wording: “Well done to the extremist section of this faith for making it impossible to have any kind of reasoned debate or even a good-humored laugh around this subject. You trump everyone, even the integrity of this feature. . . . Remember, whilst this card may be good for the purposes of the game, it’s bad for the purposes of society at large.”

Although, having accused Mr. Thompson of being humorless, I must admit that the tags he used for his piece did make me laugh: “Tags: Islam,

New Humanist

, politically correct atheist cowards.” Now that is funny.

Because of the interest, the fuss, the fantastic reception, and multiple requests for more cards, I ended up creating a second set to accompany the originals, the intention being to ultimately produce a full pack of playable cards, which would be distributed by

New Humanist

.

The second set was previewed in the March/April issue and sparked yet more requests for further sets. At the time of writing, I think we’ll be leaving it at twenty-four cards, but who knows? With more than 4,000 differing belief systems filling up the world, maybe we’ll produce more eventually.

G

RAHAM

N

UNN

Had it been necessary to apply for the position of Atheist Bus Campaign designer, I’d never have got the job. My CV, in a brief review en route to the wastepaper basket, would have shown no previous experience of design work apart from an apologetic mention under “hobbies,” and even that would have been a vain attempt to pad the whole thing out a bit. I’m the sort of person who needs to type his CV in an oversize font just to ensure the need for a staple.

I was therefore rather fortunate that it all fell into my lap. The organizer, Ariane Sherine, in a couple of comment articles for the

Guardian

, had already garnered some interest in the idea of running an alternative to the religious adverts that were appearing on London buses at the time, some of which indirectly threatened all non-Christians with eternal torment in hell. As if public transport wasn’t bad enough. Her proposal was to respond with the cheery slogan “There’s probably no God. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.” It wasn’t an altogether serious notion at first, but it became s

o as more people registered their support and asked how they could make it happen.

It was a good question. Why had nobody done it before? Perhaps they’d considered the idea of getting a large group of freethinking non-believers to work together and decided that their efforts would be better focused on tackling simpler tasks, like giving pigs the power of flight. In any case, Ariane persisted with the proposal and, knowing that I was reasonably competent with a computer, asked me if I could lend the fledgling campaign some visual impetus by creating a mock-up of how the advert might look on a bendy bus. These serpentine vehicles were cheaper to advertise on

than normal buses and were therefore a realistic target financially, despite being universally loathed by pedestrians and road users alike.

My brief was simple enough—to produce a clear, stark representation of the slogan using Ariane’s choice of colors. I duly selected a rugged-looking font, gave her a few layout options and, once the ad’s appearance had been settled upon, applied it to a bus photograph. And that was that. I was pleased that this image would be used for promotional purposes but didn’t anticipate any further involve

ment. Even if by some non-divine miracle these bus ads ever made it onto the roads, Ariane would obviously get a proper designer in for the serious stuff. With no experience of such matters, I naively assumed that you can’t produce final advertising artwork on a modest PC in your bedroom. Surely there were secret requirements that take such powers away from hapless amateurs like me? It was probably for our own good.

Anyhow, nothing was going to happen unless enough money was raised on the official donation site when it went live. This was where the idea could easily fall flat on its face, as members of the public had to be persuaded to part with hard cash. Despite the many positive comments that had been posted online, it wasn’t easy to gauge whether enough people were prepared to open their wallets, especially as the response to an earlier pledge scheme had been lukewarm. Seizing on this early event, the

Daily Telegraph

had run the headline “Atheists Fail to Cough Up for London Bus Ad” and

pronounced the idea dead with little chance of resurrection. There was soon reason for optimism, though, as the British Humanist Association had offered to administer donations to the campaign, and Richard Dawkins had also declared his support by offering to match every donation up to the target of £5,500—which meant, effectively, that only half that sum was required in total from everybody else.

Even so, I tried not to get my hopes up as I logged on for the first time that morning. According to the media, the credit crunch was stomping all over the financial markets like a video game baddie and bankers were fleeing for their bonus lives. We were all feeling the pinch. Surely a bus advert would be seen as an unnecessary extravagance while the nation collectively tightened its belt. The answer was emphatic. On

Blue Peter

they used to make elaborate “totalizers” for their appeals, which crept up slowly week by week in true “will they, won’t they?” goal-reaching drama. Had their

props team been charged with building one for the bus campaign, they would no doubt have been a bit miffed to see it become redundant before they’d finished packing up their tools.

The suddenly modest-looking target was met with almost embarrassing ease, but far from tailing off, the rate of contributions kept increasing. Administrators for the donation site reported unprecedented activity as people from all over the world gave generously, and in many cases repeatedly, leaving supportive messages as they did so. The “herding cats” analogy that is sometimes applied to atheists had been made to look rather foolish, along with any lingering doubts, as the total soared to over £100,000 in just four days. Eat that,

Daily Telegraph

! It was now clear that not only were the

buses going to happen, they were going to happen on a much grander scale than anyone had dared to anticipate.

The upshot of this was that instead of having 30 buses in central London, there would now be 800 all over the UK. Bus spotting—long the preserve of bespectacled cagoule-wearers wielding spiral-bound notepads—was now a genuinely tantalizing prospect for atheists across the country. It was fitting that many more people would get to see them, given that donations had come in from far and wide.

In spite of my doubts, I remained the official designer. I believe that, due to Ariane’s misplaced cheerleading on my behalf, the British Humanist Association were under the impression that, far from being a nerdy enthusiast with some expensive software, I did this kind of thing for a living. It was a fair assumption on their part but laughably inaccurate all the same. I wasn’t about to correct them, though. After all, the only difference between me and the professionals was that they’d gone to the terrible inconvenience of attending university and gaining a degree in the subject. Who’

s got time for all that nonsense?

I was gaining in confidence and started to feel less out of my depth. I don’t wish to denigrate the work of professional designers, of course—you’ve only got to look at some of the adverts in local services directories to see the embarrassing results of the “why pay someone when we can do it ourselves” approach—it’s just that it wasn’t the hardest of jobs to tackle. Align some text, change the colors, try not to spell

God

incorrectly . . . okay, so there was slightly more to it than that, but nothing worth boring you with. It was still reasonably straightforward, and by now I was in rec

eipt of the specifications from the advertising company, which were surprisingly straightforward and revealed that there weren’t any secret requirements after all. Thinking about it now, it would have been madness to pay a proper company an exorbitant fee to re-create what I’d already done.

As interesting as the bus advert, though, from my point of view, was the decision to spend some of the extra funds on adverts for the London Underground network. There would be four different versions, each featuring a quote from a notable atheist, which meant that more design work was required. And so I set to work again, amused by the idea that people might ponder these adverts while their faces were buried in the armpit of a fellow passenger during rush hour. Well, any distraction had to be a good one, right?

On the day of the official campaign launch, I armed myself with a cheap camcorder and hopped on the train to London. I was wearing my badge and T-shirt, which had also fallen under the design remit, and felt pleasingly out of place amid the suited commuters around me. The temperature would barely nudge above freezing all day, but a heated marquee awaited the gathering media presence, which included not only national press but correspondents from all over the world. I was meant to bring a large banner with me to hang abo

ve the stage, but unfortunately it never turned up, and the banner company claimed the courier had “lost” it. I might have believed them, but this happened not just once but twice—so I reckon they’d taken some kind of anti-atheist umbrage to it and tossed it in the Thames (although it’s more likely that the banner company had refused to print it in the first place and lied). This was a shame, not least because Ariane completely forgot that it wasn’t hanging behind her and mistakenly alluded to it in her speech.

The launch itself was a great success. On the stage we had set up easels with enlarged versions of the four different tube adverts, which were unveiled individually by the guest speakers. The mood was positive, and the complementary T-shirts were more popular than the complementary snacks. Afterward I learned that some of the press had been asking which design company was responsible for the artwork. Presumably they were going to mention it in their articles, but on learning that it was some tin-pot chancer working in his bedroom, they obviously thought better of it.

Before returning to Suffolk I made a point of stopping off at Oxford Street. The post-Christmas sales were in full flow, but it wasn’t bargain housewares that had lured me there. Opposite the Bond Street tube station were two animated screens displaying our slogan on a thirty-second rotation with the other ads. I’d knocked up the animation myself after hastily learning the basics and, to my eyes at least, it looked really good. It was the day after Twelfth Night, and it seemed like a fitting replacement for all the Christmas light displays. No one was paying much attention to the screens, a

part from me with my camcorder as I failed not to look like a weird tourist, so they probably gave me more satisfaction than anything else. These animations were later used in news reports both here and abroad as passers-by were stopped in front of them and asked for their opinions. A few shocked old ladies are always good value for a vox pop. And that, of course, was the point—not to shock old ladies, but to get people talking. Shocking old ladies isn’t big or clever.

The media coverage following the launch was extensive. The unusual nature of the campaign proved irresistible, and the story was featured on television and radio stations all over the world. While this generated extensive debate, there were only three notable adverse reactions. First, a marginal group called Christian Voice (who, somewhat ironically, I had never heard of up until this point) tried to get our adverts banned but succeeded only in exposing their general intolerance and giving us more publicity. Their leader, Stephen Green, cut a desperate figure as he spluttered his d

isapproval from a soapbox around which no one appeared to be gathered.

The second vocal objector was Ron Heather, a Christian bus driver from Southampton who had refused to do his job after seeing

one of our ads on the side of his trusty steed one morning. If Christians were looking for a heroic figure to defend their faith against the terrifying onslaught of—

scream!

—an alternative viewpoint, they couldn’t have done much worse than the limp-as-lettuce Mr. Heather. His defiant gesture was to wander home and call B

BC

Radio Solent. He enjoyed his fifteen minutes in the spotlight but didn’t do much to further his cause. If I were being childish, I could point out that he is one pen stroke away from being Mr. Heathen, but then with my surname I’m not in the best position to do so.

The third and most interesting response—for me at least—came from a political group called the Christian Party. Their leader, George Hargreaves, was someone I remembered from the Channel 4 series

Make Me a Christian

in which he had tried to imbue various unlikely candidates with a more godly outlook on life while confiscating “unhelpful” possessions such as sex toys and books on witchcraft. His success had been rather limited, to say the least, but perhaps he had agreed to the program with a wincing nod to his own past; prior to his foray into ministry he had been responsible for writing and pro

ducing pop records, among which was Sinitta’s gay disco anthem “So Macho.” Now, I would wholeheartedly agree that this act alone required a great deal of forgiveness, but becoming a reverend was perhaps one apology too far.

Anyway, it transpired that he didn’t like our adverts very much and had taken it upon himself to launch a riposte. Seemingly missing the point, as many had done, that our adverts had been a response themselves, his considered effort was to run his own bus adverts that copied ours almost entirely. The colors, the font, the layout . . . the only difference, in fact, was the wording, which now read: “There definitely is a God. So join the Christian Party and enjoy your life.” My initial reaction was one of amused confusion. Was this a brilliantly conceived appropriation or the workings o

f the least imaginative man in Britain? Was this copycat campaign just a case of So Match-o?

The answer could be found in a statement from the man himself on the party’s website. After acknowledging that his tolerance had been tested by our slogan, he quoted from Proverbs 26:5: “Answer a fool according to his folly, lest he be wise in his own eyes.” In other words, decry a rational and positive statement with one that can only be digested with a heaped spoonful of blind faith. Folly indeed. And what about “Thou shalt not steal”? Perhaps I’d missed an exemption footnote. At least ripping off our advert meant that he didn’t have to design one for himself, which you have to admit was c

lever if somewhat lazy. All he needed was a mate with the right software. Maybe Sinitta had done it for old times’ sake.

A few people asked me if I was going to take action for copyright infringement, but I think that would have been rather petty. At a glance, the Christian Party adverts looked like ours anyway, so if people were recalling the original slogan when they saw them, it was hardly doing us any harm. Some things just ridicule themselves, and so we did the decent thing and turned the other cheek. There’s a tip for you, George. Now give the nice ladies their dildos back and stop being such a spoilsport.

Atheist buses weren’t unique to the UK. Taking Ariane’s lead, other countries ran similar campaigns, including the United States, Canada, and Spain. Attempts to run ads in Italy and Australia were shelved following resistance from advertising authorities, but efforts persist. It was a pertinent reminder that the freedom of speech we take for granted in the UK isn’t as common as we might imagine. The ads in the United States carried their own slogan (“Why believe in a god? Just be good for goodness’ sake”), but those behind the campaign in Canada asked if they could use the s

ame slogan as we had. I happily sent them the artwork and was delighted to see photographs of it paraded on buses in Calgary and Toronto.