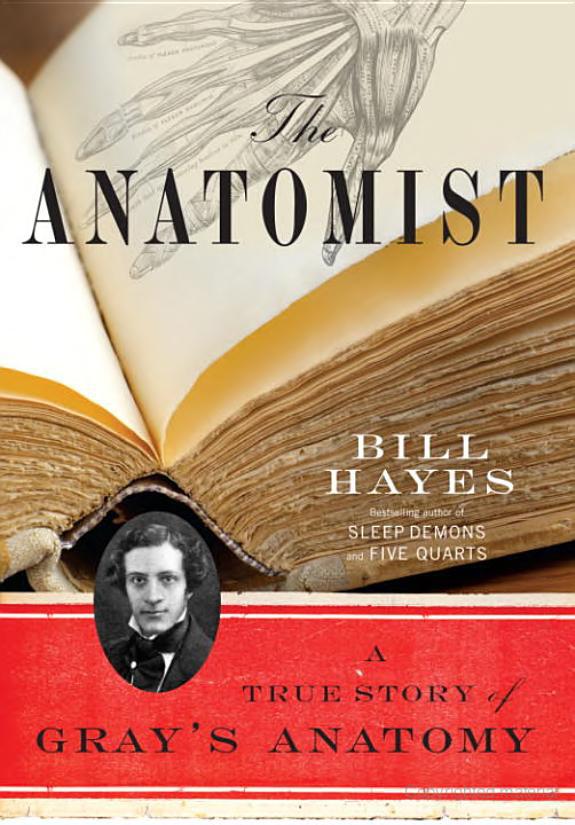

The Anatomist: A True Story of Gray's Anatomy

Read The Anatomist: A True Story of Gray's Anatomy Online

Authors: Bill Hayes

Contents

For Steve Byrne

Prologue

LOOKING BACK, I CAN SEE HOW MY WHOLE LIFE HAS LED TO THIS

: a book about a book about anatomy and about the education of an anatomist, albeit an amateur one. Sigmund Freud was right, it turns out:

Anatomy is destiny

—or mine, at least.

A bloom in a boulder crack, my fascination with human anatomy took root in the less-than-accommodating conditions of a strict Irish Catholic upbringing in the 1960s.

You are made in God’s image,

I remember being told by the nuns in catechism classes, which struck me as wonderful news; to cherish your body was to cherish the Creator. At the same time, though, the story of Adam and Eve made it frighteningly clear that the body is a shameful vessel for sin. Even today, while I no longer consider myself Catholic or even religious, the tale of their fall from innocence haunts me: God warning Adam, you shall die if you eat of the tree of knowledge, and then Eve—poor, gullible Eve—sweet-talked by the snake, pulling an apple from the tree. I still just want to stop her—

No!

“Then the eyes of both were opened; and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together.” Banishment from the garden was but one part of their sentence. “You are dust,” God tells them, “and to dust you shall return.”

The moral, simple enough for a child to grasp, is that when God says no, he really means no. But the story also conveys a more insidious notion: awareness of the body may lead to spiritual death.

To the eight-year-old me, fresh from making my first confession, Adam and Eve were especially effective in promoting the idea that nakedness went hand in hand with sin. And yet, making matters morally confusing, there were some naked people it was okay to look at, whose nakedness you were meant to take notice of, beginning, ironically enough, with Adam and Eve. Even in my children’s Bible, those two appeared as delectable as a couple of ripe Red Delicious apples. The most frequent naked body I saw while growing up, though, belonged to Jesus. In our house, crucifixes were as common as light fixtures. A small bronze one hung above my bed, and I prayed to it every night. But, in a curious design choice, as I think of it now, the largest crucifix was posted right outside the bathroom my five sisters and I shared. Jesus, as if clad in a towel rather than a loincloth, appeared to be waiting his turn for the shower. I can still recall every detail of that crucifix, a wooden one my dad had bought in Mexico. The body was carved with such care, so that legs and arms were finely muscled and veined and the torso made long and sinuous. His nakedness exposed every crucifixion wound and was crucial to reinforcing a central tenet of the church: The gash along his ribs was due to our sin. The trickle of blood down his forehead was our fault. Christ’s pain was meant to cause you the same. His death, we were never to forget, was for us.

Providing a ballast to the Irish Catholicism of my father was my mother. Mom had once been an aspiring painter in New York City before meeting Dad, and she was not Catholic. Only on the rarest occasions did Mom join us at church. I remember how, every year on Ash Wednesday, the first day of Lent, when a thumb-press of ash was placed on your forehead as a reminder of your mortality, Mom’s unsmudged brow marked her as unlike my father and sisters and me. Dad would jokingly call her “a heathen” but, almost in the same breath, say earnestly to his six children, “Mom’s a saint—that’s why she doesn’t need to go to Mass.”

To me, Mom represented the everyday, but also another, higher world—a world of artists; of passionate, driven people; a world I glimpsed in her little library of art books. Above the table where her sewing machine sat was a pinewood bookshelf that held histories of famous painters as well as exhibition catalogs from far-off places such as the Museum of Modern Art in New York. While the book

Picasso’s Picassos

only confused me, the thick tomes on Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Matisse introduced me to the sensual body as art. These books were full of nudes, not naked people, a distinction I began to understand as I edged toward puberty.

Lining the shelf on the opposite wall was our 1965

World Book

encyclopedia, twenty-two volumes, straight-spined and orderly, like the cadets in a photo nearby: the 1949 graduating class of West Point, with Dad standing third from the left, front row. It was in

World Book

volume H that I got my first peek inside the human body. Between entries on

hairstyling

and

hysterectomy,

there was a spectacular anatomical illustration composed of ten bright transparent overlays. The body illustrated was male, although, in a nod to modesty, no genitalia were shown. To this day, I still recall the smell of the plastic sheets and the sticky sound they made when you turned each overlay. Sometimes I would run up to one of my sisters and flash Encyclopedia Man in her face, eliciting a guaranteed

ick!!

—this form of teasing worked especially well on Julia, three years younger than me, and Shannon, two years older—but we would then often sit down and look at the illustrations together, drawn into the illusion of a deep body adventure, as though we wore X-Ray Specs that actually worked. Paging from left to right performed a crude dissection, salmon-colored muscle giving way to the wet worms of viscera giving way to less and less until, finally, on the last transparency, only the unadorned skeleton remained.

My two best friends’ dads were both doctors, one a G.P., one a dermatologist. Their family bookshelves held volumes that I would never be able to find even at the Spokane Public Library: old medical textbooks. Kept on topmost shelves, they were meant to be out of reach, out of sight, which is of course exactly why I would urge Chris or Andy to fetch them. What I will never forget is the deformities and disfigurements pictured: photos, as artless as mug shots, of elephantiasis, leprosy, gargantuan tumors, and other conditions that made the body seductively grotesque.

Though I confided this to neither Chris nor Andy nor any of my sisters, I dreamed of becoming a doctor one day. But whether because I did so poorly in high school biology and chemistry or because I did so well in English and writing classes, I eventually shelved the idea of a medical career. Still, my interest in the workings of the body remained; indeed, I think it intensified in direct proportion to my burgeoning interest in sex. But by the time I was actually having sex, after moving to San Francisco in the early 1980s, the body had turned virtually overnight into something to fear, a vessel not for mortal sin but for a deadly virus. That was when I bought my first copy of

Gray’s Anatomy.

I got it for the pictures: hundreds of drawings of lean muscle, bones, and organs, each meticulously rendered and labeled as if it were a rare entomology specimen. Lying on a bookstore table, the thick volume’s cover image had first drawn me in: a profile of a man whose face is intact but whose neck is not, to put it mildly. The skin from the chin to the collarbone is missing, revealing strips of muscle and a tangle of blood vessels. As gruesome as it was, I found the image incongruously beautiful. The young man wore such a serene expression, and there was something so intimate in his pose—the way his head was gently turned to expose every detail, as if in invitation:

Here, come closer, take a look.

Marked down to $9.95, the book was also a deal I could not pass up.

Gray’s Anatomy,

like

Bulfinch’s Mythology

or Plato’s

Republic,

seemed a classic every person should have—if only just to have—so I bought a copy. This was almost exactly half my life ago. Aside from occasionally spell-checking anatomical terms while writing my two previous books,

Sleep Demons

and

Five Quarts,

I ended up using the book most often to ID parts on their way out: A good friend’s cancerous pancreas. My sister’s uterus, at the time of her partial hysterectomy. My boyfriend’s pituitary gland tumor. Being able to picture the affected organs helped put those surgeries into clearer focus.

Gray’s Anatomy

became like the list of emergency numbers taped next to the phone—good in a crisis. Whenever I used the book, its language, the opposite of lyrical, always impressed me; no detail seemed too small to be harpooned with a handful of finely honed sentences. Such occasions, though, were few and far between. Like my copy of

Bulfinch’s Mythology, Gray’s

mainly collected dust on a shelf.

One day a few years ago, however, I pulled it out to double-check a spelling, and as I paged through the text, the word in question slipped from my mental grasp and a new thought surfaced:

Who wrote this thing?

I found nothing on the jacket flap but his first and last names, Henry Gray. There was no “About the Author” page in the back of the book. Curious, I checked an encyclopedia and other reference sources at home. Still nothing. Surely there must be a biography of the man, I thought, as I logged on to the public library’s online catalog. Alas, “No matches found.” So, too, said Amazon as well as those usually trusty procurers of the obscure, the International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, which struck me as odd.

Gray’s Anatomy

is widely considered one of the most famous books in the English language and is the only medical text most people know by name.

Gray’s

has been cited as a major influence by figures ranging from fitness icon Jack LaLanne to the artists Jean-Michel Basquiat and Kiki Smith. Fascinating “biographies” have been written about everything from the number zero to the color mauve, yet there is not one on Gray. Can he simply have gone unnoticed by historians, been taken for granted, as he had by me till now?

Well, no, there was a far more reasonable explanation: when trying to piece together the life of Henry Gray, the unknowns simply outnumber the knowns. What I discovered through additional digging at local libraries, in fact, is that surviving records are more extensive about his father. Thomas Gray, born in Hampshire, England, in 1787, was a private messenger to King George IV, a position in which he was entrusted to carry the most sensitive of documents, including, one can assume, the love letters sent back and forth between George and Maria Anne Fitzherbert, the king’s secret, illegal, and Roman Catholic wife. Thomas Gray later served in the same capacity for George’s successor, William IV, which suggests that he possessed a remarkable ability to be discreet and inconspicuous—a trait that he seems to have passed on to his son. To this day, it is not known where or when exactly Henry Gray was born. The year 1825 has been suggested, but 1827 is generally more agreed upon. Similarly, where he spent his earliest years is uncertain. Some historians cite London while others suggest Windsor, England, while others, connecting imaginary dots, say the lad was raised in Windsor Castle, a commoner among royalty, which is an enchanting notion but nevertheless wrong. When Henry was around three years old, Thomas Gray moved his family—wife Ann and Henry and his three siblings—into a house near Buckingham Palace, but the address itself, No. 8 Wilton Street, is the only verifiable fact of his boyhood. It is almost as if Henry Gray did not fully exist as a flesh-and-blood being until the sixth of May 1845, the day he stepped inside London’s St. George’s Hospital and signed his name to the register as a medical student.

St. George’s Hospital

From this point forward, one can retrace his path by way of exams passed, awards won, and scientific papers published, all of which are noted in official records. Among the major milestones: Gray received the equivalent of an M.D. in 1848, and four years later, at the precocious age of twenty-five, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, an exclusive group of scientists that had counted Isaac Newton and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek among its members. Still, I found it maddening that I could not scrape together more. While I had long since missed my chance at a medical career, I’d begun to hope I could make a contribution to the field as Henry Gray’s biographer. But what I had gathered about him thus far would amount to little more than a CV. No anecdotes or reminiscences about him seemed to have survived. His rise through the ranks of St. George’s is marked merely by the titles and dates of his positions, as if the man, like one of his book’s drawings, were just a neatly tagged specimen: postmortem examiner (1848), curator of the Anatomical Museum (1852), lecturer in anatomy (1854), and so forth.

Critically praised author was added to the list in 1858.

Anatomy, Descriptive and Surgical,

as Gray’s tome was originally titled, received excellent reviews, sold well, and was picked up by an American publisher the following year, by which point he was already working on a revised and enlarged second edition. In what came as a complete surprise to me, however, Gray did not create any of the book’s nearly four hundred signature anatomical drawings. These were the work of another Henry, one Henry Vandyke Carter, whose contribution was not even credited in the 1901 American edition of the book that I own. While this revelation raised a slew of new questions, others were put to rest when I learned how Henry Gray’s story ended: On Wednesday, June 12, 1861, he was scheduled to appear before the board of governors of St. George’s Hospital. As one of three finalists for a prestigious surgical position, he was expected to make a brief statement on his own behalf. But he never showed up. And word eventually reached the panel as to why. Henry Gray had died that very same day. When all the details emerged, it turned out that he had contracted smallpox while treating his young nephew who was suffering from the disease. Ten-year-old Charles Gray recovered and went on to live into his fifties, but Henry, who had been vaccinated against smallpox in childhood, died at his family’s longtime home, one week after falling ill. He was thirty-four years old.