The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society (33 page)

Read The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

It’s the nicest critical review I’ve ever had.

So is it the people, as much as the farm, that keep you in Andalucía?

Without a doubt. We’ve been made incredibly welcome here. And the Spanish rural way of life suits us. But the land has got into our blood, too. When you spend twenty-odd years building and gardening and planting trees on a plot of land, you develop a connection that runs deeper than the normal sense of

‘home’. All those repetitive chores of tilling, sowing and harvesting exert a subtle influence that affects the essence of who you are. And if you believe that you are what you eat, then we’ve become Andaluz through and through, since for two decades now we have turned the earth and pulled up vegetables, picked fruit from the trees on the terraces we’ve tended, collected and eaten the eggs from the chickens whose care is the first imperative of every day, and eaten the sheep that graze amongst the wild plants that grow on the hills around the house.

And there’s the water, too. Nearly eighty percent of us, give or take a few bottles of wine, is made up from the water from our very own spring – I’ve wondered a little what we look like inside, given the amount of limescale at the bottom of our kettle. But I feel sure this place has seeped into us. We’ve been formed by all the little griefs and agonies, and triumphs and delights, that have peppered our lives since we moved here.

So how could you ever leave a place like this? How could you sell it? How could you put up with estate agents tramping around it with notebooks and snooty clients pointing out loudly how sub-standard and illconceived everything is? El Valero was never a buying and selling property. We didn’t buy it as an investment; we bought it as a home. Which is lucky because it may well be the only property in Spain worth less than it cost twenty years before… and I’m glad because I’ve never wanted to sell the place anyway.

What do you think Spaniards in general see in the books? You’d think the humour is peculiarly English.?

I thought so, too, and the books weren’t published here for some years. But it turns out that the Spaniards find just the same bits funny as the British. They enjoy the way the rural Spanish are portrayed. I’ve had all sorts of people coming up, some of whom I didn’t know could even read, wanting to tell me the bits they find funny. That said, the urban Spaniards think that we are completely bonkers. Our farm – and the Alpujarras – is very far from the spotless way that most modern Spaniards like to live.

Translation’s a funny thing, though. I was interviewed by two young Taiwanese journalists,

who explained to me what a humorous book the Chinese had found

Driving Over Lemons.

Out of curiosity I asked them if they could translate the title. I know a bit of Chinese and it struck me as peculiarly long. They scratched their heads, then said

Sheep’s Cheese and Guitar Heaven: a Ridiculous Drama of Andalucia.

What did Chloë think about the books?

Well, she was mystified by the English title! I have a vivid memory of her worried face when she first heard us discussing it. ‘Driving Over Lemons – an Octopus in Andalucía… what on earth does that mean?’ I think she was about seven at the time. So ever since then I have been the ‘Octopus in Andalucía’.

She once said she would much rather I wrote novels: to her, my books are really just diary pieces and too familiar to be interesting. But secretly I think she gets quite a kick out of my success. A few months ago, she went to open a bank account in Granada, and as she handed across her ID card, the woman behind the counter exclaimed, ‘Ay, Chloë Stewart… you must be the girl in the book! Ay, how I loved the book.’ It’s no bad thing to be known at the bank.

Do you think Chlöe – or Ana – might write her own version of life at El Valero one day?

No. Ana has not the remotest desire to write, although she types with style and wit. (And has just reminded me that she might still go into competition with a plot for a ‘body-stripper book’). It’s hard to say with Chloë; I hope that we’ve given her a childhood that could give her something to write about. But right now she’s a university student – and has flown the nest. She shares a flat in Granada and, as you might expect, has euphorically embraced urban life. Nothing is more likely to induce an enthusiasm for all things urban than a country childhood.

So now there’s just Ana and me again on the farm, rattling like peas in a drum. This has been a tough rite of passage, and nobody tells you about it. You spend eighteen years living your life around, and for, your offspring in the most unimaginably close and intimate way… and then they’re gone. There’s nobody to wake in the morning and make sandwiches

and breakfast for before heading off to the school bus.

Of course, we get a lot of pleasure from Chloë’s happiness in her new life, and we’re proud of her independence and her making her way in the world. But it’s an odd stage, nonetheless.

What is the menagerie cast these days? You’ve got the sheep, and chickens…

It’s the same old crew really, with occasional losses due to ‘natural wastage’, which of course is where I’m headed myself. The top of the pecking order is the wife, my favourite member of the menagerie, along with Chloë – who still, I think, sees this as her home. Then there’s there the unspeakable parrot, Porca, Ana’s lieutenant and familiar, who arrived by chance to make his home with us about nine years ago. This creature is one of the villains of my second book,

A Parrot in the Pepper Tree.

The parrot dominates the five cats, who range far and wide on the farm, feasting abundantly on rats. Then there are two dogs: Big, a hairy terrier we found abandoned by the road, and Bumble, an enormous and amiable mongrel, whose function is to monopolise the space before the fire and bark at intruders. And since we’re so remote and there are few visitors, he and Big keep in practice by barking all night long at the boar and foxes and other nocturnal creatures. Which makes it hard to sleep. The dozen or so chickens earn their keep by providing us, as you might expect, with eggs. And we’ve got a colony of fan-tailed doves, which are on the increase again after a winter when a pair of Bonelli’s eagles reduced their number from around a hundred to just seven. They are more cautious now and don’t go outside much. Paco, my pigeonfancier friend and telephone engineer, is going to get me some stock from Busquistar, up in the high Alpujarra. Apparently those pigeons know how to deal with eagles, because the crags and valleys up there are thick with them.

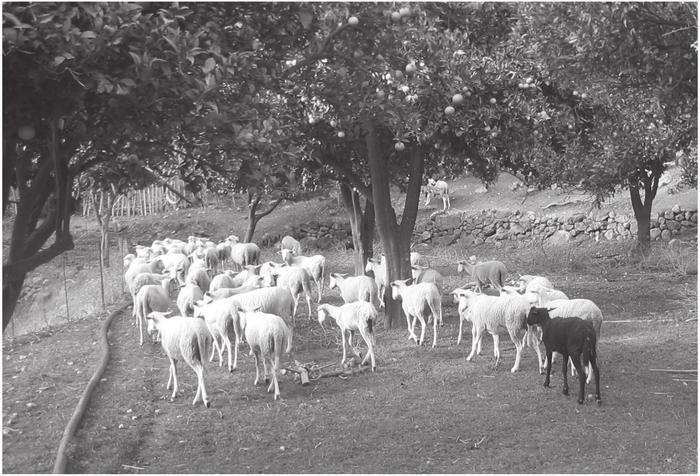

And finally there’s the sheep, and there always will be the sheep, for I cannot imagine the dull silence of the farm without the bongling of the bells and the bleating of lambs. They provide us with the most delicious meat and, take it from me, eating home-grown lamb is one of the best treats of country

life. The flock keeps the grass beneath the orange and olive trees neatly trimmed like a lush lawn. And then they range far and wide on the hills above the house, grazing on the woody aromatic plants that grow there: rosemary, thyme, broom, anthyllis, wild asparagus. At night they return to the stable, and there they copiously deposit the little heaps of beads and berries that, trodden into the straw, make the rich dung which goes to nourish the fruit and vegetables and, at one remove, us. The whole, wonderful circular ecological system.

It sounds like farming is still a passion, even if you’ve become more of a writer than a farmer?

I’ve loved farming since I discovered it at twenty-one, but if truth be told I’m not very good at it. Maybe it is a vocational gift, like medicine or music, neither of which I’m particularly good at, either. I long for the model farm, but under my care weeds seem to get the upper hand, the livestock seize every chance to destroy the plants, and every agricultural villain seems to be stalking me – mosaic virus, red spider, scale insect, aphids, blossom-end rot. You name it.

So it is lucky that, in terms of making a living, I’ve gravitated to becoming a writer. Albeit a writer who spends a lot more time farming than writing. If you’ve spent your life doing physical work it’s hard to take entirely seriously the idea of sitting down for a day’s work at a computer. I still do a bit of shearing, too, which is something I am quite good at – and which nobody else around here can do, except my-friend-aka-Domingo. So at least there’s something that enables me to hold my head up in an agricultural way.

I made a living out of shearing for thirty years, but it’s hard when you hit your fifities, and now I only do a few days a year – my own sheep, Domingo’s, and one or two other jobs in the village. I dread these shearing days because I know what a physical effort it’s going to be. But when I actually get down and stuck in, it’s like dancing a dance you knew and loved long ago. Also, I get to see my handiwork year-round, idling on the hillsides, happily scratching themselves.

And it means that people still know me around the town as the Englishman who shears sheep. I know most of the farmers and they’ll come and holler into my ear in bars. So I’ve got two different kinds of local identities. The sheep man and the book man.

Orange trees and sheep – the mainstay of the El Valero eco-system

You originally had a peasant farm with no running water, no electricity, no phone for miles around. Are things now very different?

We still rely on solar power, but more and better – enough, in fact, to run a freezer, which is a boon. Meantime, our house becomes ever more ecological. We’ve just installed ‘green roofs’ – a flat roof, lined and covered with soil and drought-resistant plants and grasses – by means of which insulation we have managed to raise the winter temperature in our bedroom to a comfortable six degrees. And we’ve got a solar water heating system that I’m currently working on.

If it weren’t for the great thug of a four-wheel drive parked on the track, our carbon footprint would be virtually nothing at all. That has become of the utmost importance to us… and, at the risk of sounding sanctimonious, so it should be to all of us.

You care a great deal about environmental issues. Do you think your views have become more trenchant since moving to Spain?

I’m not so sure about that. I was a pretty trenchant ecologist long before I moved to Spain. But one of the amazing things about writing a successful book is that people suddenly start to listen to what you have to say. This is rather gratifying, as you may imagine, but it’s not that you are saying anything different. It’s just that you no longer have to raise your voice to be heard. I think it’s the duty of anybody who finds themselves with access to the public ear to use that platform to expound ideas for reducing the sum total of human damage and misery.

The building of a dam casts a shadow over both

Driving Over Lemons

and its sequel,

A Parrot in the Pepper Tree.

How did that work out?

Well, as you can see, we’re not underwater yet. By great good luck, the authorities ended up building a dam much lower than their original plan, so unless they knock it down and start again the water level will never affect our farm. It is a sediment trap rather than a reservoir, so it’s filling up at a great rate with rich alluvial silt, which is wonderful for spreading on the land. It’s beautiful, too, the way the river meanders amongst the banks of mud, and there’s an aquatic ecosystem developing

there, with ducks and herons and legions of frogs.

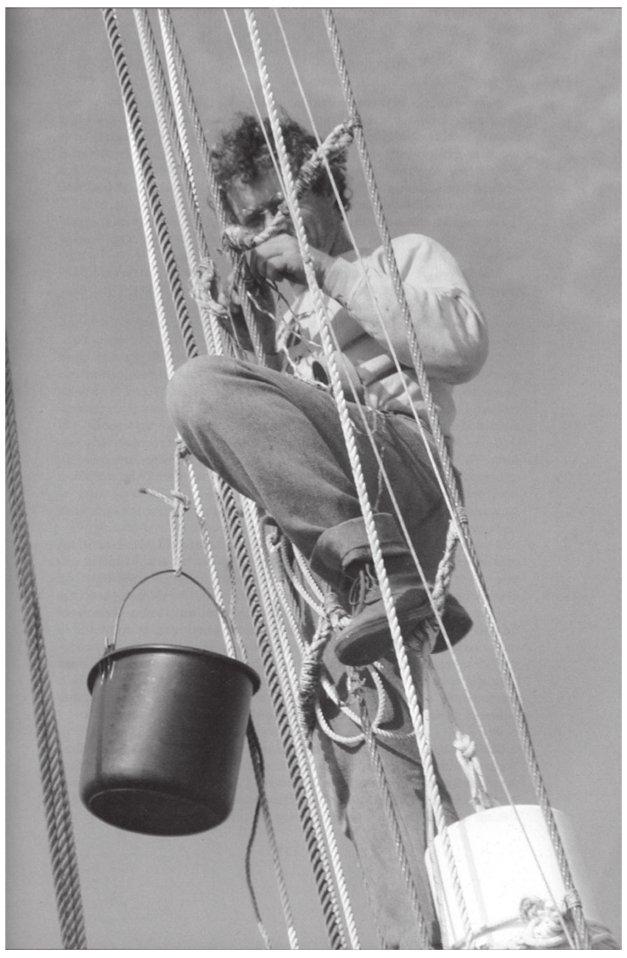

Up the mast during an epic trip across the Atlantic, told in Chris’s new book, Three Ways to Capsize a Boat

Talking of water, in your latest book,

Three Ways to Capsize a Boat,

you leave the land altogether to recall some epic and extremely funny seafaring adventures?

I’m glad you enjoyed it. Yes, Capsize is a book that I had to get out of my system. It seems odd, but I found myself writing snippets of it throughout the last ten years, maybe even longer. It was as if my mind was fixating on the sea. In buying El Valero I had to make a choice between the mountains and the coast. It’s curious how being born and raised in inland Sussex I should come to see these two types of landscape – neither of them prominent around Horsham – as somehow fundamental to my wellbeing.