The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society (31 page)

Read The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

I shouldn’t have been worried about the welfare of our neighbours’ vegetables, however, for our sheep’s designs turned out to be targeted much closer to home. It was four in the morning, on yet another hot, hot night and I was fast asleep. I was so deeply asleep, in fact, that when the sound of bells dimly percolated into the murk of my consciousness, I assumed it was a dream and rolled over. Later, as the edge of light sliding down the shutters became sharper, the sound came again and this time the dogs began to bark.

I leapt from the bed and rushed outside. There were sheep everywhere, frenetically devouring the plants that grow round the house. The dogs shot through the door barking; the sheep panicked, and rocketed as one down the steps. With Big and Bumble at my heel, I hurtled buck

naked – no time to bother with clothes – in pursuit. The flock thundered through the vegetable patch, out by the pool and hurled themselves over the stone wall, down to that part of the farm that belongs to them.

I turned and looked at what had previously been the lovingly tended fruits of Ana’s labours. It was hardly a

catastrophe

on the scale of earthquakes and hurricanes, almost farcical in fact (‘SHEEP RAVAGE VEGETABLE PATCH’). But it put me in shock, this orgy of herbivorous gluttony that had just taken place. The sheep had been eating Ana’s organic fruit and vegetables, and the flowers that were planted around them, all night long. The only things that had survived were the courgettes, which, it would seem, are abhorrent to sheep. The rest was just a miserable mess of trampled and half-masticated plants, spattered here and there with glistening

cagarrutas,

sheep turds.

I stood there in the first light of day, still wearing

nothing

but my boots, slack-jawed and appalled by the damage, and wondering how the hell I was going to break the news to Ana. But Ana was already there, stooping amongst the remains of her raspberries. She had followed me down, and as she looked about her I could hear that she was sobbing. I put my arms around her. I couldn’t think of anything to say. What

would

you say?

There was little she could say, either, though I worried at once as the words trickled out: ‘I can’t put this right… I can’t do it all over again… All that work and… and there’s nothing left…’ This was so unlike Ana – the stoic among us who always kept going, who always saw the funny side.

What was exercising me immediately, though, was to establish where the wretched sheep had got in, and to fix things so that it wouldn’t happen again. The whole

lamentable episode had, I was bitterly aware, been my fault: I was the one who had delayed feeding the alfalfa to the sheep, and I was the one responsible for the fencing. I examined the boundary minutely, looking for tracks in the dust, or wool on the thorns, but the fencing was all intact. I couldn’t make it out. There was one possibility though. We had built a high stone wall to support the terraced garden that surrounds the pool. The entrance to this terrace was contrived according to a drawing I had seen of the

fortified

entrance to the crusader castle of Crac des Chevaliers in Syria, which was conceived to discourage attacking armies, who would find themselves hemmed in amongst stone walls with defenders pouring boiling oil and other substances inimical to their well-being upon their heads. I figured this ought to scotch any incursions planned by mere sheep into that part of the farm we had designated as our garden.

I crouched down and scanned this piece of

formidable

medieval military architecture for tell tale signs.

Cagarrutas…

there were

cagarrutas

all the way up the steps. They must have been nervous. They couldn’t have got through the wooden gate, but a patch of heavily scuffed earth at the top of the wall attested to the fact that they had walked up the steps and then leapt the remaining wall. Fifty sheep – that’s two hundred scrabbly little hooves… The evidence wasn’t hard to see.

Later that morning, Manolo turned up; I found him crouched down among the remains of the vegetable patch. He turned and looked at me as he heard me enter. There was a diplomatic edge to his usual grin of greeting. ‘The sheep been here, then?’ he said, perhaps a little

unnecessarily

.

‘The buggers jumped up the wall. They’ve been here all night. They’ve had the lot. A bad business…’

‘A bad business,’ repeated Manolo, tossing a bunch of ravaged radishes onto the compost heap. ‘But not as bad as all that – a lot of this ought to come back. Maybe not those cabbages, but you don’t like cabbages anyway; you told me so yourself.’

‘No… You’re right. None of us do. I don’t know why Ana plants them. We usually end up giving them to the sheep anyway.’

‘Well, there you go, then,’ said Manolo matter-of-factly, ‘and the tomatoes and garlic will be fine, the sheep didn’t manage to break through onto the triangle patch.’ I hadn’t thought to check but this was a huge relief to hear. ‘Give me a couple of hours and I’ll have this all sorted out, and in a month you won’t even remember the sheep were here,’ he promised.

A

S

A

NA RESTORED HER EQUANIMITY

and the integrity of her vegetable patch by spending the cool of the day clearing beds, I would head down to the fields to cut bundles of fresh alfalfa for the sheep. This is one of my very favourite jobs. I used to cut the crop with a Grim Reaper-style scythe, but Manolo so ridiculed my scythe work that I’ve come round to his traditional Alpujarran way – down on my knees with the

hoz

(pronounced ‘oth’) or sickle. It’s slow work, and a little tedious, but it does groom the land in a most appealing way. The cut part of the field is left mown like a lawn, while the face of the tall, uncut alfalfa curls away like steep green cliffs and headlands. And the kneeling also puts you in touch with the insect world, that population supposed to dwarf human numbers by several million to one.

The technique is to kneel on one knee, grasp a handful of alfalfa with your left hand and sever it at the base with the sickle, repeating the process over and over again until you have a huge green bundle to hoist on your shoulders. I like to haul it straight up to the stable, where the sheep fall ecstatically upon it – there’s nothing sheep like more than alfalfa.

I remember when I was young and of a more

contemplative

cast of mind, I would lie on the edge of a pond, looking through the shadow of my head into the depths of the water. At first I’d see nothing, but little by little, as my eyes became accustomed to the scale of this

microscopic

universe, I’d begin to see the teeming population of improbable animalcules – like some tiny version of the Serengeti. Hosts of infinitesimal creatures, flippered and legged and feelered and finned, perhaps even with tiny tooth and claw, but more probably armed with suckers and cilia and palps and invasive ovipositors. Daphne there were, and hydra, and

paramecia

(if that’s the correct plural of

paramecium);

also water fleas and pond skaters and beetles, spiders and boatmen.

Well, it’s a similar thing with the alfalfa field: after a while I get bored with the repetitiveness of the work, lay down my sickle and hunker down to see what’s going on at ground level. The alfalfa becomes a towering rainforest and slowly, in the dark of its depths, the jungle population is revealed. Creatures that are metallic green and scarlet and yellow scurry about like a spill of coloured beads in constant motion. Infinitesimal spiders, pale like ghosts, cast slender lianas and lines from the forest canopy to the floor, and spin webs for the capture of creatures so tiny as to be beyond human imagination. Beetles of every

persuasion

scuttle to and fro with peculiar purpose, and

everywhere

are columns of ants, engaged in their unfathomable tasks. More sinister are the hairy black caterpillars, giants wriggling through the green penumbra; Manolo tells me these huge beasts can reach plague proportions and devour whole crops of alfalfa, though, touch wood, that has never happened to us.

Higher in the canopy are the ladybirds, thousands of them, all welcome allies in the battle against the

piojos

– aphids – in the orange trees. And fluttering above the canopy are clouds of small blue butterflies; they look as if the alfalfa flowers themselves, which are a similar blue, have taken wing and come to life.

It was lucky that, in order to fit in with Ana’s astrological plans, our tomatoes had been moved to the sheep-proof triangle patch by the alfalfa, for a summer without

tomatoes

would be unthinkable. Above all else, tomatoes are the basis for gazpacho and, in common with most of the population of Andalucía, we make and eat gazpacho almost every day from July till September.

People are passionate about the way to make true

gazpacho

, or their own version of it: there are those who abhor, for example, the use of a cucumber; others who insist upon the juice of a lemon rather than vinegar. I add a fistful of basil and mint and leave the peppers out – and Domingo, who, it has to be said makes a good and gutsy gazpacho, tells me that the secret is to add a dash of honey. Now, part of the beauty of gazpacho – for us, at any rate – is the fact that in summer we can usually gather all the ingredients,

apart from the honey, fresh from the garden. This lends the dish an extra sanctimonious appeal.

Using honey from our own hives would, doubtless, be an even greater pleasure, and well-intentioned people have for years suggested we keep bees. And maybe we should, but then these same folk also counsel us to keep goats and make our own cheese, plough with our own mules,

slaughter

pigs for the pork and sausages, make our own wine and yoghurt and jams, and plait our own esparto grass into ropes and baskets. No thanks, we reply: we want more free time rather than less.

It’s curious how enthusiastic friends can be about ideas that would fill our lives with more work and drudgery; things they wouldn’t dream of doing themselves, but that seem to them just the thing to keep us from succumbing to boredom in our rural idyll. I have to admit, though, that we do feel a little tempted by bees; it would seem like the right thing to do for the farm. Bees are somehow fundamental to existence – why, Albert Einstein himself reckoned that if the bees went humanity would soon follow. But our farm is thick with wild bees anyway, and sometimes the humming from the eucalyptus or the blossoming oranges rivals even the sound of the rivers.

So for the present we leave beekeeping to the

beekeepers

. And besides, the whole business of keeping bees is fraught with difficulties. There’s the crop plane that sprays the valley with dimethoate, which is fatal to bees, and then there are the inevitable diseases which take their toll, not to mention the depredations of the

abejarucos,

the bee-eaters. The valley swarms with these beautiful birds. They live in the holes in the rocks above our neighbour’s farm, La Herradura, and swoop down across the road as you drive

past, winging their way out high across the valley. This gives you the opportunity to watch them from above as they twist and turn and hover and stall. And as the sun catches them they shine with all the colours of the most florid parrots you could imagine. The

abejarucos

are the most spectacularly exotic creatures that live here, and they fill us with wonder and delight. Of course the beekeepers take a different view, because bee-eaters do eat an awful lot of bees.

Chloë has become party to Domingo’s affectation of putting honey in the gazpacho, and to humour her I usually add a spoonful or two. But that month our supplies ran out, and on a whim I decided to walk up to collect supplies from Juan Díaz, our favoured beekeeper, who lives high on Carrasco, the lush spring-watered hill that bounds the valley on its western side. I could have taken the car I suppose, but it wouldn’t have been the same; there was a certain romance in the idea of slogging up a hill on a hot summer day to fetch a pot of honey.

By the time I reached the little grove of walnut trees below Juan Díaz’s

cortijo,

my shirt was sticking to my skin and the cotton rag with which I wipe the sweat from my brow was limp and sodden. The sun hung

motionless

directly overhead, burning my nose and ears, and the super-heated air lay still and heavy. I stopped beneath the shade of a tree and looked out across the gulf of still air to Campuzano, the waterless hill on our own side of the valley. It had been eighteen months now without a drop of rain and the scrub-covered slopes were dull with that yellowish pallor of dying vegetation.

Approaching the house, I passed an open-cast rubbish dump, the universal element of a traditional Alpujarran farm, and called out to announce my presence. The Díaz house is, like many in the Alpujarras, built on a

camino

or mule track, so in following the way you pass right through its porch. Receiving no reply, I ducked under the

overhanging

vine and passed through to where the track continued on the other side.

There, holding a tin bucket, stood Juan’s wife, Encarna, a strong, bright-eyed sixty-year-old, who was wearing, in spite of the heat, an apron over an old floral printed dress, over a pair of woollen trousers.

‘Hola, vecino,’

she cried – Hallo, neighbour. ‘And what brings you up this way?’

‘Hola,

Encarna…

Qué tal?’

She wiped her hands on the apron and shook my hand. ‘Hot,’ she said – the Spanish talk about the weather just as much as the British – ‘Hot, and still no rain. It’s all going to ruin… but what can we do? We must just put up with what we’re given, no?’

This particular philosophical discourse is an almost formulaic greeting, and doesn’t really require an answer.

Juan was apparently seeing to his bees in the little poplar copse just up the slope behind the house. ‘Go and find him,’ she urged. ‘He loves to show people the hives.’

‘Okay, I will’, I answered and walked apprehensively off in the direction she indicated.

Juan Díaz, a tall, thin man whose grey hair and aquiline nose were hidden under a large veil, was leaning over a wooden box in the spindly shade of the poplars, engaged in one of those arcane tasks that beekeepers do. Half of him was obscured by a cloud of smoke and bees. He saw me and

nodded his head discreetly in greeting. ‘Come on over and take a look, Cristóbal, but gently,’ he intoned.

‘Not bloody likely, Juan. It’s alright for you – you’re veiled.’

‘So you’re nervous of the little bee, then?’

Spanish bees tend to be aggressive, so I don’t feel in the least feeble declining to poke around them without a veil. I watched from a safe distance as Juan broke the propolis seal of a hive and lifted its lid. The murmuring of the bees rose a little in pitch and the hundreds of bees that obscured his person turned into thousands. They crawled all over him, scores of them moving on his bare hands. He seemed perfectly calm, moving with a measured delicacy. Actually I thought it unlikely that a bee could get its sting into Juan’s hands anyway, given the cracked-leather texture of his work-hardened skin. He had told me that he cauterised the deep fissures that followed the folds of his hands and fingers by filling them with gunpowder – yes, gunpowder from a shotgun cartridge – and setting light to it. Juan Díaz was hard.

‘What are you doing there, Juan?’ I called in a manner calculated not to aerate bees. He was silent for a while as he performed a particularly tricky part of the operation. Eventually he said: ‘I’m looking for the queen. I think she may have escaped into the upper part of the hive. But I’ll leave it for now. It can take a long time to find a lost queen.’

He gently put back the lid and exchanged his veil for a battered straw hat proclaiming his affiliation to the ‘Caja Rural’ – the Country Bank – and came forward to shake my hand. Then he led me to the small store at the back of the house where he kept his honey. Most of the year’s crop

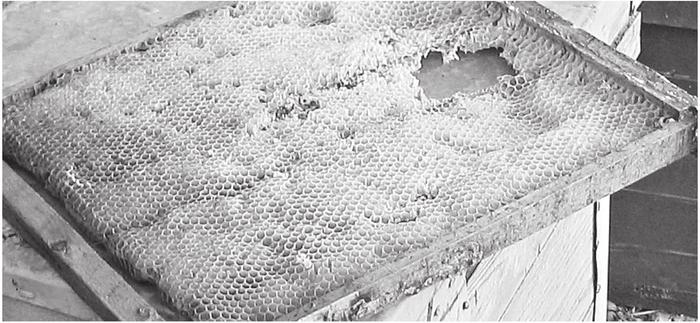

was still settling in a big plastic tub. On the surface was a thick crust of pollen, dead bees, flakes of wax and general detritus from the hive.