The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future (17 page)

Authors: Chris Guillebeau

How can you construct an offer that your prospects won’t refuse? Remember, first you need to sell what people want to buy—give them the fish. Then make sure you’re marketing to the right people at the right time. Sometimes you can have the right crowd at the wrong time; marathon runners are happy to eat donuts after the race, but not at mile 18. Then you take your product or service and craft it into a compelling pitch … an offer they can’t refuse.

Here’s how you do it.

1. Understand that what we want and what we say we want are not always the same thing

.

The next time you get on a crowded plane and head to your cramped middle seat in the back, with a screaming infant seated behind you at no extra charge, remember this principle. For years travelers have been complaining about crowded planes and cramped seats, and for years airlines have been ignoring them. Every once in a while, an airline creates a campaign to respond to the concern: “We’re giving more legroom in coach!”

It sounds great, but a few months later they inevitably reverse course and remove the extra inches of space. Why? Because despite what they say, most travelers don’t value the extra legroom enough to pay for it; instead, they value the lowest-priced flights above any

other concerns. Airlines have figured this out, so they give people what they want—not what they say they want. A good offer has to be what people

actually

want and are willing to pay for.

2. Most of us like to buy, but we don’t usually like to be sold

.

An offer you can’t refuse may apply subtle pressure, but nobody likes a hard sell. Instead, compelling offers often create an illusion that a purchase is an invitation, not a pitch. Social shopping services such as Groupon (see

Chapter 8

) and Living Social have been successful in recruiting their customers to do most of their marketing for them. Indeed, the biggest complaint about these businesses is often that they sell out of deals too quickly, also known as “They won’t let me give them my money!”

As you might imagine, the path of least resistance is a good place to stand. Visitors to Alaska quickly understand why a $100 coupon book is worth much more than $100. Marathon runners do not need to be sold on the benefits of fresh oranges after three hours of running. Adventurous college students will grasp the value of a $20,000 “go travel somewhere and do what you want” fellowship without much explaining.

Offer Construction Project

MAGIC FORMULA: THE RIGHT AUDIENCE,

THE RIGHT PROMISE, THE RIGHT TIME =

OFFER YOU CAN’T REFUSE

BASICS

What are you selling? ______

How much does it cost? ______

Who will take immediate action on this offer? ______

BENEFITS

The primary benefit is ______

An important secondary benefit is ______

OBJECTIONS

What are the main objections to the offer?

1.

2.

3.

How will you counter these objections?

1.

2.

3.

TIMELINESS

Why should someone buy this now?

What can I add to make this offer even more compelling?

3. Provide a nudge

.

The very best offers create a “You must have this right now!” feeling among consumers, but many other offers can succeed by creating a less immediate sense of urgency. Providing a gentle nudge to encourage immediate action separates a decent offer from a high-performing one. Let’s look at a few examples.

EXAMPLE 1: THE YOGA STUDIO

Jonathan Fields, a hedge fund lawyer turned fitness entrepreneur, owned a Manhattan yoga studio that sought to be at the top of the

market. A single class cost $18, and membership cost $119 a month. Toward the end of summer, the studio saw a significant drop-off in business, but when October rolled around, people got back to their routine and started coming in more often.

Jonathan wanted to find a way to inspire people to come back earlier than expected and get as much commitment from them as possible. He had an idea for an offer they couldn’t refuse: Starting September 1, first-time members could get unlimited classes through the end of the year for $180. This was essentially four months of yoga for the price of 45 days, or 62 percent off the normal price. Two additional factors were added to make it even more interesting: First, the sooner a new member signed up, the more classes he or she could attend, thus creating instant urgency. Second, the offer could be withdrawn at any time; if someone came in on September 3 and wasn’t sure about committing to the rest of the year, the staff made sure to let that person know that the offer might not be available later in the week.

Thanks to New Year’s resolutions, most fitness centers take in the bulk of their new members in January. Jonathan’s strategy helped his business gain a big increase in September, traditionally a difficult month. Also, September was close enough to January that by the time the new year rolled around, many of the members were committed enough to transfer to a monthly plan—at the regular price.

EXAMPLE 2: THE INEFFICIENT BUSINESS MODEL

(MARKET INEFFICIENCY = BUSINESS OPPORTUNITY)

Whenever something is more complicated than it should be or any time you spot an inefficiency in the market, you can also find a good business idea.

Priceline.com

took advantage of hotel inefficiencies by creating a system that allowed consumers to book rooms at name-brand hotels for much less than the retail rates. Then other companies took

advantage of Priceline’s lack of transparency by creating a business model that allows travelers to know which hotels Priceline works with. Each of these models includes a compelling offer:

Priceline’s compelling offer: Save 40 percent or more on name-brand hotels, guaranteed.

Third-party compelling offer: Learn exactly which hotel you’ll get with Priceline … and save even more when you know exactly how much to bid.

You can also derive a powerful business model from traditional systems that lack transparency. If you want to make a traditional real estate agent mad, ask the agent about Redfin, the Seattle-based service that splits commissions with home buyers. I learned this lesson when one agent told me that Redfin “should be illegal” and that I was doing a disservice to hardworking people by endorsing it. Why are (some) agents so testy, and why should it be illegal to save consumers money? Oh, because the money is coming from the pockets of real estate agents, who are used to receiving full, hefty commissions regardless of the amount of work they perform. Redfin has succeeded by challenging gatekeepers and addressing a huge inefficiency in the marketplace.

Speaking of home owners, the DirectBuy franchise was started in order to offer “ordinary people” (i.e., non-contractors) access to retailer pricing on appliances and home electronics. To get around the concerns of retailers and manufacturers, DirectBuy structured its business model on charging a flat fee for consumers to join. The compelling offer is: Invest in our membership, and you’ll save thousands on home remodeling.

†

EXAMPLE 3: THE GRAPHIC FACILITATOR

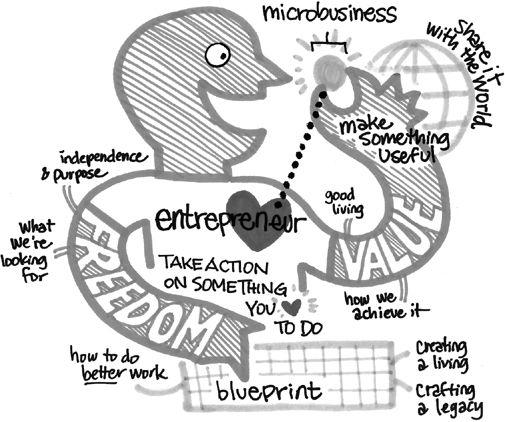

I’ll invite you to meet Brandy Agerbeck in these pages, but you can “meet” her first by examining the mindmap she made for us below.

‡

Brandy runs a business of one, with the philosophy “never have a boss, never be a boss.” Creating graphical representations of ideas—usually those expressed in meetings, retreats, or conferences—is Brandy’s full-time work. Over the last fifteen years, she’s worked with hundreds of clients at all kinds of events. It’s a beautiful business model from a talented artist, but it also raises a question: How do you nudge or win over executives who don’t get it at first?

From countless interactions about the valuable service she provides, here’s what Brandy learned. She starts every initial conversation by saying, “I have a fantastic, strange job.” This creates curiosity and also serves to make the other person not feel bad if he or she is unfamiliar with the world of graphic facilitation. Next, Brandy learned that her target market may be the executives or meeting leaders she serves, but they aren’t necessarily the ones who hire her. “I am most often hired by facilitators, acting as their visual silent partners,” she says. “They can focus entirely on their client knowing their process, and progress is documented.”

After nearing the end of a five-hour drive from Boise to Salt Lake City, I stopped off at a Starbucks about twenty minutes away from the bookstore I was speaking at that evening. On the way inside, I grabbed something from the trunk and left the keys inside. Nice move, Chris. It was even worse because I didn’t realize my mistake until I had finished my latte and email session an hour later, shortly before I was due to arrive at the bookstore.

I was mad at myself for being so stupid, but I had to think quickly. Using a combination of technology (iPod touch, MiFi, cell phone), I located the number of a local locksmith and quickly rang him up. “Uh, can you please come as soon as possible?” He agreed to be as fast as he could.

Much to my surprise, the locksmith pulled up in a van just three minutes later. Impressive, right? Then he got out his tools and approached the passenger door. In less than ten seconds, he had the door open, allowing me to retrieve my keys from the trunk and get on with my life. “How much do I owe you?” I asked. Perhaps it’s because I don’t own a car and the last time I paid a locksmith was

ten years ago, or maybe I’m just cheap, but for whatever reason I expected him to ask for something like $20. Instead, he said, “That will be $50, please.”

I hadn’t discussed the price with him before he came out and was in no position to negotiate, so I gave him the cash and thanked him. But something was unsettling about the transaction, and I tried to figure out what it was. I was mad at myself for locking my keys in the car—it was obviously no one’s fault but my own—but I also felt that $50 was too much to pay for such a brief service.

As I drove away, I realized that I secretly wanted him to take longer in getting to me, even though that would have delayed me further. I wanted him to struggle with unlocking my car as part of a major effort, even though that made no sense whatsoever. The locksmith met my need and provided a quick, comprehensive solution to my problem. I was unhappy about our exchange for no good reason.

Mulling it over, I realized that the way we make purchasing decisions isn’t always rational. I thought back to something that had happened in the early days of my business. I had produced a twenty-five-page report on booking discount airfare and sold it for $25. Many people bought it, but others complained:

Twenty-five pages for $25? That’s too expensive

.

I knew I couldn’t please everyone, but I didn’t understand this specific objection. The point of the report was to help people save money on plane tickets, and many readers reported saving $300 or more after one quick read. “What does the length of the report have to do with the price?” I remember thinking about that one complaint. “If I gave you a treasure map, would you complain that it was only one page long?” It turned out the joke was on me. All of us place a subjective value on goods or services that may not relate to what they “should” be.

Just as what we want and what we say we want aren’t always

the same thing, the way we place a value on something isn’t always rational. You must learn to think about value the way your customers do, not necessarily the way you would like them to.

FAQ, Guarantee, and Overdelivery

As you continue to work on your offer, three tools will assist you in making it more compelling: the FAQ page (or wherever you provide the answers to common questions), an incredible guarantee, and giving your customers more than they expect. Let’s look at each of them in detail.

1. Frequently Asked Questions, AKA “What I Want You to Know”

You might think that a frequently asked questions (FAQ) page is designed merely to answer questions. Surprise! It’s not … or at least, that’s not its only function. A well-designed FAQ page also has another, extremely important purpose. You could call it “operation objection busting”: The additional purpose of a FAQ is to provide reassurance to potential buyers and overcome objections. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to identify the main objections your buyers will have when considering your offer and carefully respond to them

in advance

.

Wondering what the objections to your offer will be? They fall into two categories: general and specific. The specific objections relate to an individual product or service, so it’s hard to predict what they might be without looking at a particular offer. General objections, however, come up with almost any purchase, so that’s what we’ll look at here. These objections usually relate to very basic human desires, needs, concerns, and fears. Here are a few common ones: