The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future (13 page)

Authors: Chris Guillebeau

Persuasion marketing is still around and always will be, but now there’s an alternative. If you don’t want to go door to door with a vacuum cleaner in hand, consider how the people in our study have created businesses that customers desperately want to be a part of.

What do you sell? Remember the lesson from

Chapter 2

: Find out what people want and find a way to give it to them. As you build a tribe of committed fans and loyal customers, they’ll eagerly await your new offers, ready to pounce as soon as they go live. This way isn’t just new; it’s also better.

When you’re brainstorming different ideas and aren’t sure which one is best, one of the most effective ways to figure it out is simply to ask your prospects, your current customers (if you have them), or anyone you think might be a good fit for your idea. It helps to be specific; asking people if they “like” something isn’t very helpful. Since you’re trying to build a business, not just a hobby, a better method is to ask if they’d be willing to pay for what you’re selling. This separates merely “liking” something from actually paying for it.

Questions like these are good starting points:

• What is your biggest problem with ______?

• What is the number one question you have about ______?

• What can I do to help you with ________?

Fill in the blanks with the specific topic, niche, or industry you’re researching: “What is your biggest problem with getting things done?” or “What is the number one question you have about online dating?”

The fun thing about this kind of research, especially the open-ended questions to which people can respond however they’d like, is that you’ll often learn things you had no idea about before. It’s also a way to build momentum toward a big launch or relaunch, something we’ll look at more in

Chapter 8

.

You can ask for input either on a small, one-on-one basis or on a group basis. To check with a broader group of respondents, I use

a paid service provided by

SurveyMonkey.com

, but you can also create a free, less sophisticated version with Google Forms (available within Google Docs). Write to your group of respondents, tell them what you’re thinking about, and ask for help. It’s good to keep the survey very simple: Ask only what you need to know. All of us are busy, but if you construct a good survey, the response rate can be 50 percent or higher.

Once you’ve moved beyond the basics and have a good idea of what you’re hoping to offer, you can take this process further. I often write to my customer list and ask about specific product ideas, like this:

Here are a few projects I’m thinking about working on during the next few months, but I could be totally wrong. Please let me know what you think of each idea.

Idea 1

Idea 2

Idea 3

etc.

I then apply a simple ranking scale to each idea and ask the respondents to stick with their first impression. The ranking scale usually consists of answers such as “I love it!” “You should do it,” “Sounds interesting,” “Would need to hear more,” and “It’s not for me.”

Generally speaking, it’s good to keep surveys to less than ten questions or so. To get more overall responses, ask fewer questions. To get more detailed responses (but from fewer people), ask more questions. It’s up to you, but make sure that whatever you ask is something you actually need to know about. Pay close attention to

the feedback; it will either confirm your intention to proceed or make you think about restructuring your proposed project.

Either way, the information is valuable, but also remember that the majority opinion isn’t everything. Among other concerns, you’ll need your own motivations for building a project over time. If your motivations are based strictly on the preferences of someone else, you’ll run the risks of boredom, unhappiness, and simply being less purposeful than you could be otherwise. The lesson is to use surveys but use them carefully. Sometimes, deciding not to pursue a promising project or deliberately turning away business is one of the most powerful things you can do. (See “The Customer Is Often Wrong” for a story about that.)

The Customer Is Always Right Often Wrong

It was a big launch day, which meant I was up by 5 a.m., coffee in hand and ready to go. As the new website went live, hundreds of customers were ready and waiting to purchase. I watched the shopping cart fill up and closely monitored the in-box for support issues.

Happily, the launch was successful. By noon, more than a thousand people had purchased, and that number would double by the end of the day. I had sent so many customer thank-you emails that Google briefly shut down my email account, thinking I was a spammer. A friend at the company rescued me by restoring the account, and I went back to plowing through messages. In the in-box were hundreds of notes from excited new customers, as well as dozens of minor support requests: “I lost my password,” “The site is down,” “How can I change my log-in?” and so on.

And then there was Dan. The note from Dan read, “I’d like a refund.” I wrote him back quickly, “No problem, but what’s wrong?”

“Let me give you some free advice,” Dan wrote in a tone that was obviously sarcastic. “Give me a call and I’ll tell you how you lost my business.”

I looked at the shopping cart and the site comments—several orders and dozens of excited messages were coming through every minute—and replied to Dan: “Sorry, I can’t call you. I’ll issue the refund and I wish you well, but I don’t need any advice right now.”

You’ve probably heard the expression “The customer is always right,” but most small business owners quickly discover this is not true. Yes, you want to focus on meeting people’s needs and going above and beyond them whenever you can, but any single customer does not always know what’s best for your whole business. These customers may not be the right ones for your business, and there’s nothing wrong with saying farewell to them so you can focus on serving other people.

I didn’t have time to call Dan on launch day, and perhaps I missed a good opportunity to learn from him. But I’m pretty sure it was the better decision to get back to work on my core market instead of spending time with one disgruntled customer who had already received a refund.

As you learn more about your customers and what they want, you may find yourself overwhelmed with ideas. What should you do when you have more ideas than time to pursue them? Two things: First, make sure you’re capturing all the ideas and writing them down, since you might want them later; second, find a way to evaluate competing ideas. Creating a “possibilities list” helps you retain ideas for when you have more time to implement them.

Most of the time, however,

having

an idea isn’t a problem for entrepreneurs.

†

Once you begin to think of opportunities, you’ll probably end up with no shortage of ideas written on napkins, scrawled in notebooks, and floating around in your head. The

problem is evaluating which projects are worth pursuing, and then deciding between different ideas. Sometimes you may know intuitively what the best move is. In those cases, you should proceed without hesitation. Other times, though, you’ll feel conflicted. What should you do?

The decision-making matrix will help you evaluate a range of projects and separate the winners from the “maybe laters.” Putting something off doesn’t mean you’ll never do it, but prioritization will help you get started on what makes the most impact. First of all, keep in mind the most basic questions of any successful microbusiness:

• Does the project produce an obvious product or service?

• Do you know people who will want to buy it? (Or do you know where to find them?)

• Do you have a way to get paid?

Those questions form a simple baseline evaluation. If you don’t have a clear yes on one of them, go back to the drawing board. Let’s assume, however, that you can answer yes to all of them but know you can’t pursue five big projects at one time. In that case, you’ll need some method of evaluation. Here’s one option: the decision-making matrix.

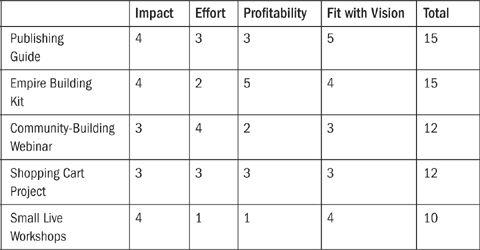

In this matrix, you’ll list your ideas in the left-hand column and then score them on a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being the highest. Granted, the scoring will be subjective, but since we’re looking for trends, it’s OK to estimate. Score your ideas according to these criteria:

Impact

: Overall, how much of an impact will this project make on your business and customers?

Effort

: How much time and work will it take to create the project? (In this case, a lower score indicates more effort, so choose 1 for a project that requires a ton of work and 5 for a project that requires almost no work.)

Profitability

: Relative to the other ideas, how much money will the project bring in?

Vision

: How close of a fit is this project with your overall mission and vision?

Rank each item on a scale of 1 to 5 and then add them up in the right-hand column. Remember, you’re looking for trends. If you have to cut one project, cut the lowest one; if you can only take on one project, proceed with the highest one.

Here’s an example from my own business, when I was deciding which business projects to pursue in the second half of 2011:

When you don’t know where to start and have a bunch of ideas, this exercise can help. In my case, the live workshops would have a big impact on the people who attended them (or so I hoped) but not on anyone else. They would require a great deal of prep time and energy and wouldn’t be very profitable. Therefore, I put them on hold.

The decision-making matrix also helps you see the strengths and weaknesses of your ideas. I liked the idea of small live workshops until I realized they would require a great deal of work for little reward and impact. That was a big weakness! On the other hand, a project like the webinar represented a middle ground: I didn’t expect the workload to be overwhelming, and I expected it to deliver above-average (although not amazing) results.

When we last left off with James Kirk in

Chapter 1

, he had moved from Seattle to South Carolina and opened the coffee shop he had been thinking about for the last six months. What happened next? As he settled into a slower way of life and got to know his customers, he made a few changes. “I learned there was no way you could have a breakfast place down here and not sell biscuits,” he said. “If you had told me back in Seattle that my coffee shop would sell biscuits, I would have laughed.” He also sold a great deal of iced tea almost every day of the year, something that would be ordered only once in a while on a hot summer day in the Pacific Northwest.