Ted & Me (7 page)

Authors: Dan Gutman

The Kid

“WAKE UP!”

I woke up.

Ted Williams was screaming at me. For a few seconds, I didn't remember where I was or

when

it was. I thought that maybe I was late for school. But my mom never yelled at me like that. It was like a bomb had gone off.

“What time is it?” I asked, bolting upright from my makeshift bed on the floor.

“Eight thirty!” he shouted. “What, are you gonna waste your life away? Let's go get some grub.”

The guy was amazing. He could go from being perfectly nice to a screaming maniac and then back again in an instant. It was as if he could turn it on and off like a light switch.

I pulled on the same shirt I had been wearing the day before and went to the bathroom. There was some

toothpaste in there called Pepsodent, which I had never heard of. On the tube were the words “You'll wonder where the yellow went when you brush your teeth with Pepsodent.”

I used my finger as a toothbrush. The Pepsodent stuff didn't taste bad. Then Ted and I went to a little coffee shop around the corner from the hotel.

I decided not to ask him whether he was going to play or take the day off and finish the season at .3995535. I was afraid I had already said too much and that I had influenced his decision. But he brought up the subject himself.

“I'm going to go for it,” he said quietly as we waited for the waitress to get to our table. “You want to know why?”

“Why?”

“Because if I sat on the bench today,” he whispered, “for the rest of my life I would know in my heart that I took the easy way out. And The Kid never takes the easy way out.”

The Kid. I had never met anybody before who talked about himself as if he was another person. It was a little strange.

“You're making a good decision,” I told him.

“I made another one too,” he added as the waitress arrived. “You're coming with me.”

We ordered eggs and toast, but I could barely taste them. I couldn't stop thinking about how lucky I was. I was sitting across the table from one of the

two greatest baseball players of his age (the other one being Joe DiMaggio), and I was going to be a witness to the greatest day of his career.

I would wait until later to bring up Pearl Harbor, I decided. And hopefully, there would be time after the game to talk him out of enlisting in the military so he wouldn't lose all those years of playing ball. It was all good.

Ted gobbled down his eggs as if he thought somebody would steal them off his plate. He no longer seemed to care about where my parents were or why a thirteen-year-old kid from Louisville was hanging around Philadelphia all by himself. He was focused on the task at hand: to hit .400 for the season. While he ate, I noticed that his fingernails were chewed down to the quick.

Nobody recognized Ted in the coffee shop. Either that or they pretended not to. He paid the bill and we stepped outside. It was a gray day. That could be good for a hitter, I thoughtâno shadows.

It was Sunday, so there weren't a lot of cars on the street. But when Ted put his hand up in the air, a taxi almost magically appeared.

“Shibe Park,” Ted said as we climbed in.

The driver recognized Ted.

“I'm an A's fan,” he said, “but today I'm rootin' for you, Mr. Williams. Good luck out there.”

“I'm gonna need it,” Ted replied.

We drove through the streets of Philadelphia, passing all kinds of stores. I noticed the movies that

were playing in the theaters:

Citizen Kane. Abbott and Costello in the Navy. Dumbo. Million Dollar Baby

, starring Ronald Reagan. I laughed to myself when I saw a sign on a movie theater that boasted

WE HAVE AIR-CONDITIONING!

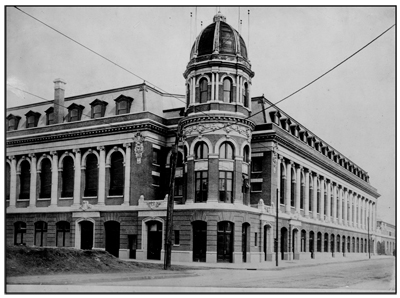

In about fifteen minutes, we pulled up to a big building at the corner of Lehigh Avenue and 21st Street. It filled the whole city block, but it didn't look like a ballpark at first. There was a dome at the corner that made it look a little bit like a church. But there was a sign that said

SHIBE PARK.

A smaller sign said

TODAY: ATHLETICS VS. BOSTON RED SOX.

It looked almost like a church.

Athletics. I always thought that was a dumb name for a team. Of

course

they were athletic. They were professional athletes. That's sort of like naming a basketball team the Philadelphia Tall Guys.

I wasn't sure, but I didn't think that Shibe Park was still around in the twenty-first century. Neither were the Philadelphia Athletics. I recalled reading that they had moved to Kansas City at some point and later to Oakland. Maybe if they changed their name to something other than Athletics, they could stay in one town.

Players need to get to the ballpark hours before game time, of course. There were only a few fans milling around: the hardcore autograph seekers. Even so, six or seven newsboys were on the corner hawking their papers. Each one had a different newspaper. I reminded myself that there was no internet in the 1940s. No CNN. They didn't even have

television

yet. People got their news from the newspaper, so there had to be more of them.

I peered out the window of the taxi. The men all wore hats, of course. The women wore bright red lipstick. General admission was $1.10. You could get a bleacher seat for 50¢.

“Fifty cents!” I exclaimed.

“Highway robbery,” Ted said.

He told the taxi driver to pull around to the players' entrance to avoid the fans. But as soon as we stepped out of the cab, Ted was accosted by a guy with a pad and pen.

“Oh, crap,” Ted muttered as the guy approached. “I can't stand this cockroach.”

“G'morning, Ted,” the guy said cheerfully.

“Well, if isn't Dave Egan of

The Boston Record

,” Ted sneered. “The Knight of the Keyboard. I see they let you out of your cave.”

“You gonna play today, Ted?” Egan asked. “Or take the easy way out and coast to .400?”

“You think I'd give

you

the scoop, Egan?” Ted snapped. “Take a hike! You'll find out soon enough when they post the lineups.”

Egan scribbled something in his pad.

“What do you think of the rumors that, after the season is over, the Sox are gonna trade you to the Yankees for DiMaggio?” he asked.

“No comment,” Ted said. “But I'd sure love a crack at that dinky little rightfield fence in Yankee Stadium. If I played half my games there, I'd probably hit 80 homers a year.”

Egan smiled and scribbled in his pad.

“Ted, how do you respond to critics who say you're selfish?” Egan asked. “They say you don't come through in the clutch. They say you wait for walks, and you're not aggressive enough at the plate.”

“I'd give 'em a knuckle sandwich,” Ted said. “Did any of those creeps ever hit .400?”

Egan laughed. He seemed to enjoy taunting Ted, and Ted seemed to enjoy giving it right back to him. But he'd had enough. He was anxious to go inside and get ready for the game.

“Hey, who's your little friend?” Egan asked, pointing at me with his pen.

“None of your business,” Ted replied. “Look, I've got better things to do than make small talk with

you

, Egan. So scram.”

“Good luck today, Ted.”

Ted replied by spitting in Egan's direction. Then he pulled open a door that led to a tunnel that led to the visitors' locker room. I asked him if he wanted me to be his batboy or something, and he said I could do whatever I want. Nobody would care. I guess when you hit .400, you can do anything you'd like

and nobody can do anything about it.

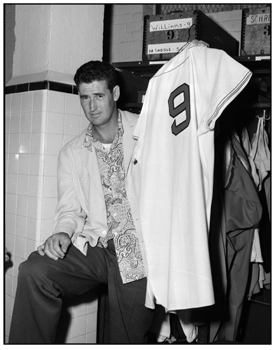

Ted at his locker.

We walked into the locker room, and it was filled with guys playing cards, reading letters, and smoking. In those days, they didn't know that smoking caused cancer.

Ted walked in like he owned the place.

“Hey, Whale Belly!” he shouted to the first guy he saw. “How's it goin'?”

He shook hands all around, calling teammates Sport or Meathead or various combinations of curse words.

“Didn't expect to see

you

here today, Teddy,” a player with glasses said. “Thought you'd take the day off and coast.”

“I never coast, Dommie,” Ted replied. “I go full speed all the way.”

That was for sure. If Ted Williams had been around in the twenty-first century, he would probably have been diagnosed with ADD or hyperactivity or something. From the moment he walked into the locker room, he was in constant motion: talking non-stop, clapping guys on the back, cracking jokes. He seemed wired, edgy. I wasn't sure if he was always like that or if he was particularly pumped up and nervous on this day. Finally, he went to put his uniform on.

I looked around, just taking it all in. The players were putting on those old-fashioned, heavy, gray flannel uniforms with buttons down the front. None of them had long hair, a beard, or a mustache. And

none of them were African-American or Hispanic. It would be six years, I calculated, before Jackie Robinson would break the color barrier.

The uniforms didn't have the players' names on the backs, but names were written on masking tape above each locker. I noticed Bobby Doerr, who is a Hall of Famer most people don't know about. Jimmy Foxx was another Hall of Fame name I recognized. He was a really big guy, with huge arms. No wonder Ted was doing pushups in the hotel room the night before.

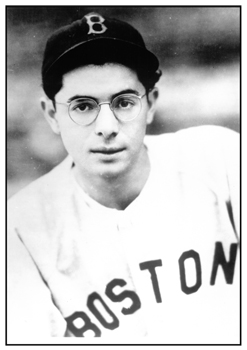

Dom DiMaggio

The guy Ted called Dommie had the word DiMaggio taped above his locker, and I remembered that Joe DiMaggio's brothers Dom and Vince were also major-league players. Dom DiMaggio wore number seven and had black, wavy hair parted in the middle. With those thick glasses, he didn't look like a ballplayer.

Ted pulled on his number nine jersey and hopped up on a table so the trainer could wrap tape around his right ankle. He had told me that he'd chipped a bone back in spring training, so he had to get his ankle taped every day.

I wandered around the locker room trying to pretend I belonged. The batboy, a skinny kid who was chewing gum, didn't seem to mind me being there. He spent most of the time reading comics:

Superman, Tarzan, Mutt & Jeff.

There was a bulletin board on the wall with the baseball standings tacked up on it. I saw that the Red Sox were in second place at 83-69, 17 games behind the Yankees. The Philadelphia Athletics were far behind in last place with a record of 63-89. They must be pretty bad, I figured.