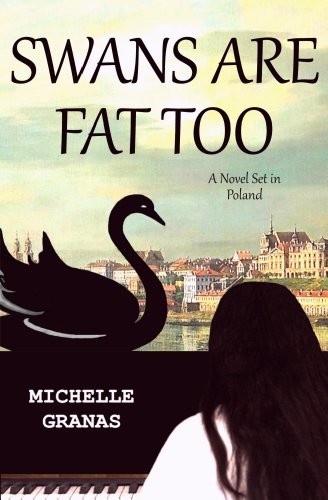

Swans Are Fat Too

Authors: Michelle Granas

Tags: #Eastern European, #Literature & Fiction, #Contemporary Women, #World Literature, #literary, #Contemporary Fiction, #women's fiction

SWANS ARE FAT TOO

Michelle Granas

Table of Contents

Acknowledgement:

I am grateful to Louise Burns at Andrew Mann Ltd. for her kind support and assistance.

Notes and Disclaimers:

All the characters are figments of my imagination. All their actions––including those of the gondola-keeper––are made up. There are no Radzimoyskis (or at least that's not what they're called).

I have simplified the usual Polish spelling of some characters' names.

I have simplified many other matters as well. This is a novel and its references to past events are intended primarily to suggest the outline of a history being compiled by the characters. Sources are noted at the end of the book.

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Warsaw Uprising are different events.

This story was written in 2006.

LCCN: 2014902894

Copyright © 2014 Michelle Granas

ISBN: 9780988859289

1

Heartless, soulless, a human skeleton;

Youth! Lend me wings!

–

Adam

Mickiewicz

,

'Ode to Youth,' 1820

"What do you think she'll be like?" Kalina turned to her brother.

Maksymilian shrugged, hiking his glasses up on his nose, and speaking in his squeaky voice. "Some

babsztyl

, I suppose. We'll get rid of her. We got rid of the last one and we can take care of this one too." He spoke with quiet determination. There had been blood and a knife and a lot of screaming. It hadn't affected him. He was ready to carry on.

"But this one's our cousin," said Kalina. "It could be dangerous..." Maksymilian shrugged again.

*

Hania Lanska, descending from the airplane at Okęcie in Warsaw, knew nothing of what was awaiting her. She had missed the funeral, she thought, as she lugged her bag along the corridor and tried to avoid being buffeted by the hurrying passengers. She was hurrying too––not that it mattered now, after the fourteen-hour delay at take-off in New York. It was so stupid to have come all this way, just too late.

"No excuses!" The image of her grandmother rose before her. A large––a vast––woman, with thin hair slicked back in a bun and piercing eyes, standing erect and ferocious beside a grand piano. "There are no excuses!" she would snap as she rapped on the piano lid with…with what? She had always been rapping with something. A ruler? A stick to beat time? To beat her pupils? "There is no excuse for making a mistake. Concentrate!" Rap, rap, rap.

And then the music would begin again, the beautiful music emerging somewhere between the student's red and concentrating face and frantically working fingers.

She would certainly not consider Hania had an excuse for missing her funeral. And yet truly, there had been no help for it: they had been kept "for security reasons" locked in the JFK gate area for all those hours.

Only once had the airline brought round food. She'd thought she would starve. The portions on the flight over hadn't been very large either. Quick marching with her flight companions, her eyes searched the airport for a vending machine. Please let there be a candy bar somewhere, she thought, as she hurried along. She was weary, rumpled-feeling, distressed, and really, a little chocolate would have been welcome.

Customs was coming up. She felt in her bag for her passports as she walked, pushing the American one down and pulling the Polish one out. Here she was. Would she fit past the booth? Always she had this fear, but it was ridiculous really. Of course she would fit. The uniformed guard gave her a cursory glance and stamp-stamped her passport. She was through; she only bumped the sides a little because she was tired and it made her clumsy.

She came up panting to the conveyor belt. All the suitcases were black or dark green and nearly identical. All were being snatched off in great hurry. She wondered if hers had departed with a stranger. She didn't like to push through the crowd, though, as other people were doing. If she lost her luggage, so be it, she wasn't going to join the melee.

It was so stupid to have come too late. Her arrival at this hour would no doubt cause her aunt and uncle difficulties. She had telephoned this morning, just before the plane left. She wondered if they would be here to meet her. Her aunt hadn't said, but she'd asked for the arrival time. It was dark out and late. She hadn't been in Poland since she was a teenager––seven-eight years ago, and then only briefly.

What did the streets look like now, and her cousins, and what music had they played at the funeral?

She watched as a dark green canvas bag was tipped over the end of the belt by a woman struggling with two small children and an oversized frame-case. She waited a moment till the spot cleared and then stepped quietly forward and claimed her bag. Now to see if anyone was waiting.

She walked through the doors into the gauntlet of people, the line of searching faces behind the barrier, the hugs and kisses as passengers were claimed. There was no one she knew. She wasn't sure she'd recognize her relatives anyway and they probably wouldn't recognize her. She flinched from the occasional glance that slid over her, curiosity dying. No, no one came toward her. She stopped and looked around. Already the crowd was thinning. No one had come to meet her. She had thought it very likely and yet she was disappointed. She was jet-lagged and flat-feeling and alone. Perhaps they were too busy. No doubt there had been many things to do in connection with the funeral.

'Though they would certainly not be prostrated with grief. Natalia Lanska, concert pianist, had been much admired, had been adored––by people outside her own family. If any one of her nearest kin had felt for her, it was only she herself, Hania thought––and more out of compassion than anything else. Yet she had missed her funeral.

She would just have something to eat at the little café there. She turned towards it, and as she did so she saw the closed sign go up on the cash register and someone turned out the light.

Two men in mustaches were approaching her, asking simultaneously in broken English if she needed a taxi, ignoring one another, talking over each other. No, she wanted to say, I want something to eat! Still, it was getting on for nine-thirty and Wiktor and Anna would no doubt be waiting for her.

She liked the looks of the second taxi driver better, but nodded okay, in Polish, to the first to speak, and followed him through the glass doors into the night. The warm air wrapped around her, and the smell of diesel and pavement. Then she was in the taxi and they were speeding along the avenue––a smooth, spruced-up, anywhere-in-the-world sort of avenue between trees. The potholes would begin later. She tried to look out at the city. Here it was still the outskirts. Trees and garden plots and billboards. So many billboards. What was that Ogden Nash bit?

I think that I shall never see

A billboard lovely as a tree…

Such an inconsequential thought but she smiled a little to herself and turned her gaze ahead as they came up too fast on the tail of another car and swerved at the last moment away to the right. Did the taxi driver really have to slalom so? In and out among the traffic, and wasn't that a red light they just went through? It was! She sank down in her seat. Thank goodness they were getting now into the city proper and he had to slow down some. There were streets of old buildings, stuccoed buildings with wrought-iron balconies and pilasters, and crowding behind and between, great modern constructions of glass and steel had sprung up everywhere. And here they were coming to downtown. Amazing how full the streets still were of people at this hour. Smart young men and women, with fashionable haircuts, laughing at café tables, leaning towards one another intently to tell a secret, make a point, leaning back in their seats to enjoy the joke. She almost wished she could tell the taxi driver to stop, could get out and join them, sit at a café and have a nice time with friends, have something to eat. They went on though, and soon they were passing embassies and parks, turning down tree-lined streets, and the taxi was pulling up too abruptly before a pre-war building of rather dilapidated mien.

"Here?" the driver asked, twisting in his seat to look at her in disapproval. "Are you sure?"

"Yes," she said, looking out uncertainly. Of course it was the building. She'd spent the first six years of her childhood here. It just looked unfamiliar, somehow. Perhaps it was the surroundings that had changed, been cleaned up, new buildings added, leaving No.17 looking shabby and out of place. She paid the driver and got out and as she faced the tall carriage entrance ahead of her, with its forbidding doors, she rather wished the taxi hadn't left so quickly, with a squeal of the tires. She was alone in the street. Not that she was afraid of the Warsaw night, only she felt suddenly reluctant at the thought of meeting her aunt and uncle. She was not shy, but she was very sensitive to other people's feelings––including their feelings toward her. Perhaps they wouldn't be very glad to see her. Her heart contracted a little. Deep within, a little voice prompted that she was always unwanted. It was true, she knew, but she hushed it at once. Still, she couldn't linger in the street for ever.

She approached the dark entrance. A panel of the heavy iron grillwork guarding the passage stood open. Hidden now by the night, the passage's vaulted roof held a pattern of criss-cross lozenges and large swathes of chipping paint, she recalled. Beyond was a lightless courtyard surrounded by walls of windows; the door she wanted was here though. There was an intercom, but it was dangling by its wires; obviously it didn't work. She tried the door and it swung open, letting her into a cool, black, high-ceilinged entry-way. It smelled of mold and cleaning detergent. Her grandmother's apartment––her uncle's now, that is––was on the third floor, she remembered, fumbling for the light switch––which had been here, along the wall. The light sprang on and lit her halfway to the first landing and then went out again, plunging the staircase in darkness. A small amount of light came in from the tall windows and she chugged on up with her heavy suitcases. Maybe, she thought, she would ring at the door and her aunt and uncle would fling it open with cries of delight. They would crowd around her with hugs and apologies for missing her at the airport and offers of refreshment. They would say how glad they were to see her again. They would make her feel welcome and at home…Maybe––but probably not.

Something was different here but she couldn't think what. She remembered the black art nouveau balustrade and the patched marble steps. It was probably just the late hour, and how long she'd been away. Still, it felt a little eerie.

It had been her father who had decided she should come. "Someone from the family should attend," he had said, "I can't possibly get away, but you're free. Why don't you go? It would be good for you."

When something was inconvenient for him to do himself, he always thought it would be good for her. Still, this time she hadn't minded. She did want to attend the funeral, and she wasn't busy. She had just finished a year as a music teacher at a private school. The year was over, she was out of work and the next months were empty unless she found a summer job.

There weren't a lot of positions available for failed concert pianists. She was––had been––one of the best pianists in America, and that meant one of the best in the world, give or take a few ten thousand. She knew it, and her teachers knew it, and one of them had finally said to her, "It's no use, you don't have the stage presence, you'll never make it as a performer, I don't care how good you get. You're wasting my time and yours."

"But I could learn presence, couldn't I?" she had asked pitifully. She hated to remember it.

The reply had been brutal. "You're not eccentric; you're not good looking. You're obese. You haven't a chance."