Strong Motion (45 page)

The next morning she returned to the Square, had her hair clipped, and shopped some more. She was standing in front of a clothing-store mirror, seeing if she could manage a lime-green skirt with a less than straight cut, when her reflection’s eyes suddenly caught her own and she was stricken by the thought that all she was doing was trying to look like Lauren Bowles.

She decided she’d bought enough for now.

The Mustang turned heads as she drove north with the top down through Cambridge and Somerville. She took the inside lane on I-93. The only disheartening thing was that she couldn’t stand any of the music on the radio.

The air in Peabody smelled like seaweed. On Main Street, a block east of the Warren Five Cents Savings Bank, she knocked twice on the window of

The Peabody Times

before she saw the sign saying

CLOSED THIS FRIDAY

. She leaned against a fender, pressing the thin fabric of her skirt against the sun-heated metal, and chewed down three fingernails as far as seemed advisable.

On Andover Street she located the middle-aged bank building that she’d seen pictured as a newborn in the

Globe

from 1970. Rust now stained the panels it was faced with; the sidewalk was cracked and tanned and weedy. Across the street stood a laundromat, a video rental place, and a “spa” selling beer and groceries. The man behind the spa counter was a Portuguese who said he’d owned the business for six years. She tossed the bottle of Pepsi she’d bought into the back seat of the Mustang.

She cruised the working people’s neighborhood behind the bank building, past white bungalows nearing condemnation, through varying concentrations of acetone fumes, up and down all the streets that dead-ended against the high corporate fence with its signs saying

ABSOLUTELY

NO TRESPASSING. She stopped by a house with a white-haired man on the porch. He staggered across his lawn, favoring a bad hip, and stared at her as if she were the Angel of Death who had come along in her red Mustang sooner than he’d expected. She said her name was Renée Seitchek and she was a seismologist from Harvard University and could she ask him a few questions? Then he was sure she was the Angel and he hobbled back to his porch and from this position of relative safety shouted, “Mind your own business!”

She tried other streets and accosted other old men. She wondered if there was something in the water that made them all so bizarre.

A stumpy woman turning the soil around some apparently dead roses saw her drive by for a third time and asked what she was looking for. Renée said she was looking for people who’d been in the neighborhood since at least 1970. The woman set down her hand spade. “Do I get some kind of prize if I say yes?”

Renée parked the car. “Can I ask you some questions?”

“Well, if it’s for science.”

“Do you remember sometime about twenty years ago a particularly tall . . . structure on the property over there, that looked like an oil well?”

“Sure,” the woman said immediately.

“Do you remember what years?”

“What’s this got to do with earthquakes?”

“Well, I think Sweeting-Aldren may be responsible for them.”

“I’ll be damned. Maybe they want to fix my kitchen ceiling.” The woman laughed. She was built like a mailbox and had a wide mouth, painted orange. “Jesus Christ, I can’t believe this.”

“My other question is whether you might have any old pictures that would show the, uh, structure.”

“Pictures? Come on inside.”

The woman’s name was Jurene Caddulo. She pointed at the gray crater in her kitchen ceiling and wouldn’t budge until Renée had found the right combination of phrases to express her sympathy and outrage. Jurene said she was a secretary at the high school and had been widowed for eight years. She had five thousand unsorted snapshots in a kitchen drawer.

“Can I offer you a cordial?”

“No thanks,” Renée said as bottles of apricot liqueur, Amaretto, and Cherry Heering were set down on the table. Jurene came back from another room with a pair of exceptionally ugly cut-glass tulips.

“If you can believe I’ve only got two of these left. I had eight until the earthquakes. You think I can sue? They’re antiques, they’re not available. You like Amaretto? Here. That’s good, isn’t it.”

Expired coupons punctuated the disordered photographic history of Caddulo family life. Jurene’s daughter in Revere and daughter in Lynn had hatched children in a variety of shapes and sizes; she puzzled over group shots, trying to get the names and ages right. Renée found herself saying, “This must be Michael Junior,” which made Jurene look again at the other pictures because she knew that this was

not

Michael Junior and therefore the child she had just called Michael Junior must be Petey, and then everything made sense again. Jurene’s younger son played guitar. There were dozens of prints of a picture of his band playing the heavy-metal mass that he had written at the age of seventeen and that the priest had said no to performing in the church, so it was performed right here in the basement without the sacraments. The son now had a different band and drove a customized 4x4 pickup. The older son showed up as an adult in San Francisco sporting a mustache and a leather vest, and as a distant, gowned blur in blue-toned shots of a high-school graduation on a dreary day. Jurene said he was a hair stylist. Renée nodded. Jurene said both her sons were still looking for the right girl. Renée nodded. In high school and junior high the daughters had worn their no-color hair in fantastic bouffants. Their bodies were deformed like pool toys by the affectionately squeezing tentacles of their father, now dead of cancer. All the sadness of the seventies was in Jurene’s drawer, all of the years in which Renée had not been happy and had not had what she wanted but instead had had pimples and friends who embarrassed her, years whose huge tab collars and platform soles and elephant flares and overgrown hair (Don’t the mentally ill neglect to cut their hair?) now seemed to her both the symbols and literal accoutrements of unhappiness.

Jurene still went to the same cottage she’d been renting for twenty years in Barnstable, on the Cape. She was going there Sunday. “After I’ve been at the Cape I can smell the smell here for about two days before I’m used to it again. You want to know something really peculiar, though, sometimes on the Cape I can smell it at the beach.”

“It’s like a ringing in your ear, except in your nose.”

“No, I’m talking about the smell. Here.” Jurene produced a handful of low-resolution pictures of a snowman and a snow fort and a snowball fight in the little front lawn. In the background of every one of them, well behind the houses across the street, was Sweeting-Aldren’s drilling derrick. There was nothing else it could be; no chemical process that Renée knew of required a structure like that. The date was stamped on the back: February 1970. “Can I have one of these?”

“Borrow ’em, sure. Why don’t I see if can find the negatives.” She opened a drawer in which negatives were under such pressure that some of them sprang out and fluttered to the floor. She left them there while, on second thought, she opened a tin of butter cookies and arranged them on a painted plate. Renée held her glass of Amaretto to the graying light in the window. A label on the bottle said

According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects

.

“I have to go,” she said.

♦

The sky was deepening as if the land were on a slope and sliding towards a precipice. In the parking lot of an office complex affording a good view of Sweeting-Aldren, she sat on the hood of the Mustang with the Caddulo pictures and a 7

1

/

2

-minute USGS topo map, comparing perspectives on a cooling tower, trying to triangulate a location for the derrick. Thousands of pig-sized and cow-sized boulders, some of them possibly glacial and native, shored up the hillside on which the complex stood.

A voice spoke from right behind her: “What ugly children.”

She turned and weathered a spasm of fright. Rod Logan was standing by the car, holding a picture that had been lying on the hood.

“Give me that,” she said.

Behind her in the parking lot, junior executives were walking to their shiny cars. Rather than risk a scene, Logan handed her the picture. He strolled to the brink of the asphalt and peered down at the yellow pond below the boulders.

“You know,” he said, “in the old days, people like you, they’d come around, they’d get warned, and if they kept coming around they’d have the shit beaten out of them, and nobody would really complain or litigate, it was just part of the way the game was played. But everybody’s gotten so gosh-damed kind and gentle lately. It’s reached a point where all I can really do is ask you politely to clear out, and if you choose not to, we’re no longer on terra firma, if you know what I mean. We don’t know what kind of procedures are required. There’s no literature on it.”

Renée got in the car.

“This is quite the stylish car, incidentally. Nice duds, too. Looks like you’ve found a wealthy patron.”

She started the engine. Logan leaned over her, looking straight down on her lap.

“Goodbye, Renée.”

♦

She made another trip to the Square, stopping at the clinic in the Holyoke Center and then dropping off the Caddulo negatives for enlargements. The rest of the weekend, late into both nights, she worked at a console in the lab. Not a single person disturbed her until Sunday afternoon, when a few students drifted through, said hello, executed Diane, etc. No one looked at what she was writing.

Her abstract read:

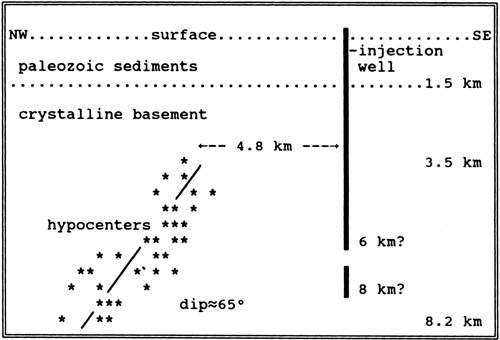

Recent seismicity in Peabody, Mass., and the prolonged sequence in 1987 have displayed the swarm-like character of known instances of induced seismicity. Until now the resemblance has been disregarded because of the relatively great focal depths of the earthquakes (3-8km) and the absence of reservoirs and injection wells in the focal area. However, photographic and archival evidence strongly indicates that in 1969-70 Sweeting-Aldren Industries of Peabody drilled an exploratory well to a depth in excess of 6 km, and that the well has subsequently been used for waste disposal. Current research locates observed activity on a steeply dipping basement fault striking SW-NE. Models of fluid migration and fault activation are proposed, the temporal distribution of observed seismicity is explained, and the legal implications of Sweeting-Aldren’s role are briefly discussed.

She described the tectonic environment of the Peabody earthquakes. She marked likely well-sites on the best of her aerial photographs. In footnotes she mentioned Peter Stoorhuys and David Stoorhuys by name. She made pictures:

She wrote that the absence of earthquakes between 1971 and 1987 indicated that there were no stressed faults in the immediate vicinity of the injection well. It had taken as long as sixteen years for fluid to be forced far enough into the surrounding rock for it to reach the fault(s) on which the earthquakes were taking place. This indicated that very significant volumes of waste had been injected, and that the rock formation at a depth of 4 km was loose enough to accept this volume at pumping pressures low enough to be commercially attractive. The conventions of scientific prose served to clarify and heighten the passion with which she wrote. She was so absorbed in her arguments that it shocked her, at the mirror in the women’s bathroom on the second floor, to see the expensive, tarty clothes she was wearing.

♦

Monday afternoon, after sleeping late, she picked up the Caddulo enlargements, bought some red nail polish, and stopped by the Holyoke Center again. Back in Hoffman she saw a flabby, sunburnt woman standing in the hall outside her office, looking very lost. Brown daisy-shaped pieces of felt were sewn onto the chest of her yellow sweat suit and the thighs of her yellow sweatpants; a button pinned to her shoulder said

ADOPTION NOT ABORTION

. Renée had heard that people like this were still dropping in from time to time, but she hadn’t seen one personally since the week her phone and mail harassment started.

The woman sidled up to her and spoke confidentially. She had a twang. “I’m looking for a Dr. Seitchek?”

“Oh,” Renée said indifferently. “She’s dead.”

“She’s dead!” The woman drew her head back like an affronted hen. “I’m very sorry to hear that.”

“No, I’m joking. She’s not dead. She’s standing right in front of you.”

“She is? Oh, you. What’d you say you’re dead for?”

“Just a joke. Let me guess what you’re here for. You came to my abortion clinic to complain to me personally.”

“That’s right.”

“Clairvoyant,” Renée said, touching her temple. She saw that Terry Snall had stopped at the bottom of the staircase. He had his hands on his hips and was exuding tremendous discombobulation over the way she was dressed. She turned her back to him. “Let me ask you,” she said to the visitor. “Does this building look to you like an abortion clinic?”

“You know, I was just wondering that myself.”

“Well, you see, it’s not. And I’m not a medical doctor. I’m a geologist.” On an impulse, she spun and pointed. “Terry, though. Terry performs abortions. As a sideline, don’t you, Terry?”