The Child Bride

Authors: Cathy Glass

Certain details in this story, including names, places and dates, have been changed to protect the children.

HarperElement

An imprint of HarperCollins

Publishers

77–85 Fulham Palace Road,

Hammersmith, London W6 8JB

and HarperElement are trademarks of

HarperCollins

Publishers

Ltd

First published by HarperElement 2014

FIRST EDITION

© Cathy Glass 2014

A catalogue record of this book

is available from the British Library

Cover layout design © HarperCollins

Publishers

Ltd 2014

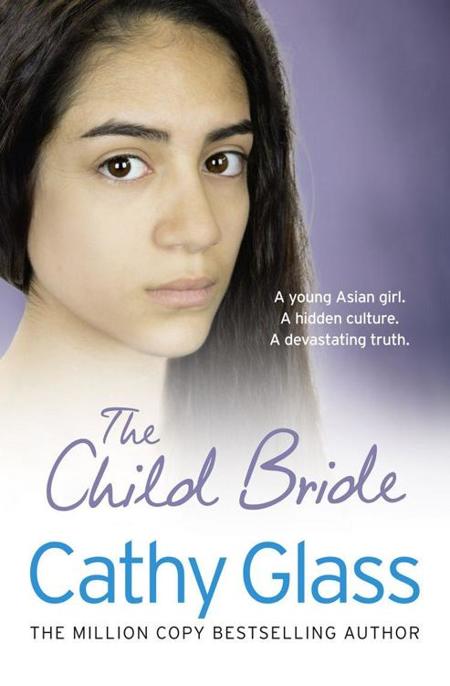

Cover photography by Nicky Rojas (posed by model)

Cathy Glass asserts the moral right to

be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at

Source ISBN: 9780007590001

Ebook Edition © September 2014 ISBN: 9780007590018

Version 2014-08-14

Chapter Five: Scared into Silence

Chapter Eleven: Worries and Worrying

Chapter Thirteen: Consequences

Chapter Fifteen: Vicious Threats

Chapter Sixteen: Zeena’s Story

Chapter Seventeen: A Special Holiday

Chapter Twenty-One: Police Business

Chapter Twenty-Two: The Suitcase

Chapter Twenty-Three: Other Victims

Chapter Twenty-Four: The Silence Was Deafening

Chapter Twenty-Five: Heartbreaking

Chapter Twenty-Six: Turn of Events

Chapter Twenty-Seven: More than I Deserve

Damaged

Hidden

Cut

The Saddest Girl in the World

Happy Kids

The Girl in the Mirror

I Miss Mummy

Mummy Told Me Not to Tell

My Dad’s a Policeman (a Quick Reads novel)

Run, Mummy, Run

The Night the Angels Came

Happy Adults

A Baby’s Cry

Happy Mealtimes for Kids

Another Forgotten Child

Please Don’t Take My Baby

Will You Love Me?

About Writing and How to Publish

Daddy’s Little Princess

A big thank-you to my editor, Holly; my literary agent, Andrew; Carole, Vicky, Laura, Hannah, Virginia and all the team at HarperCollins.

A small child walks along a dusty path. She has been on an errand for her aunt and is now returning to her village in rural Bangladesh. The sun is burning high in the sky and she is hot and thirsty. Only another 300 steps, she tells herself, and she will be home.

The dry air shimmers in the scorching heat and she keeps her eyes down, away from its glare. Suddenly she hears her name being called close by and looks over. One of her teenage cousins is playing hide and seek behind the bushes.

‘Go away. I’m hot and tired,’ she returns, with childish irritability. ‘I don’t want to play with you now.’

‘I have water,’ he says. ‘Wouldn’t you like a drink?’

She has no hesitation in going over. She is very thirsty. Behind the bush, but still visible from the path if anyone looked, he forces her to the ground and rapes her.

She is nine years old.

Petrified

‘And she wouldn’t feel more comfortable with an Asian foster carer?’ I queried.

‘No, Zeena has specifically asked for a white carer,’ Tara, the social worker, continued. ‘I know it’s unusual, but she is adamant. She’s also asked for a white social worker.’

‘Why?’

‘She says she’ll feel safer, but won’t say why. I want to accommodate her wishes if I can.’

‘Yes, of course,’ I said, puzzled. ‘How old is she?’

‘Fourteen. Although she looks much younger. She’s a sweet child, but very traumatized. She’s admitted she’s been abused, but is too frightened to give any details.’

‘The poor kid,’ I said.

‘I know. The child protection police office will see her as soon as we’ve moved her. She’s obviously suffered, but for how long and who abused her, she’s not saying. I’ve no background information. Sorry. All we know is that Zeena has younger siblings and her family is originally from Bangladesh, but that’s it I’m afraid. I’ll visit the family as soon as I’ve got Zeena settled. I want to collect her from school this afternoon and bring her straight to you. The school is working with us. In fact, they were the ones who raised the alarm and contacted the social services. I should be with you in about two hours.’

‘Yes, that’s fine,’ I said. ‘I’ll be here.’

‘I’ll phone you when we’re on our way,’ Tara clarified. ‘I hope Zeena will come with me this time. She asked to go into care on Monday but then changed her mind. Her teacher said she was petrified.’

‘Of what?’

‘Or of whom? Zeena wouldn’t say. Anyway, thanks for agreeing to take her,’ Tara said, clearly anxious to be on her way and to get things moving. ‘I’ll phone as soon as I’ve collected her from school.’

We said a quick goodbye and I replaced the handset. It was only then I realized I’d forgotten to ask if Zeena had any special dietary requirements or other special considerations, but my guess was that as Tara had so little information on Zeena, she wouldn’t have known. I’d find out more when they arrived. With an emergency placement – as this one was – the background information on the child or children is often scarce to begin with, and I have little notice of the child’s arrival; sometimes just a phone call in the middle of the night from the duty social worker to say the police are on their way with a child. If a move into care is planned, I usually have more time and information.

I’d been fostering for twenty years and had recently left Homefinders, the independent fostering agency (IFA) I’d been working with, because they’d closed their local branch and Jill, my trusted support social worker, had taken early retirement. I was now fostering for the local authority (LA). While it made no difference to the child which agency I fostered for, I was having to get used to slightly different procedures, and doing without the excellent support of Jill. I did have a supervising social worker (as the LA called them), but I didn’t see her very often, and I knew that, unlike Jill, she wouldn’t be with me when a new child arrived. It wasn’t the LA’s practice.

It was now twelve noon, so if all went to plan Tara and Zeena would be with me at about two o’clock. The secondary school Zeena attended was on the other side of town, about half an hour’s drive away. I went upstairs to check on what would be Zeena’s bedroom for however long she was with me. I always kept the room clean and tidy and with the bed made up, as I never knew when a child would arrive. The room was never empty for long, and Aimee, whose story I told in

Another Forgotten Child

, had left us two weeks previously. The duvet cover, pillow case and cushions were neutral beige, which would be fine for a fourteen-year-old girl. To help her settle and feel more at home I would encourage her to personalize her room by adding posters to the walls and filling the shelves with her favourite books, DVDs and other knick-knacks that litter teenagers’ bedrooms.

Satisfied that the room was ready for Zeena, I returned downstairs. I was nervous. Even after many years of fostering, awaiting the arrival of a new child or children is an anxious time. Will they be able to relate to me and my family? Will they like us? Will I be able to meet their needs, and how upset or angry will they be? Once the child or children arrive I’m so busy there isn’t time to worry. Sometimes teenagers can be more challenging than younger children, but not always.

At 1.30 the landline rang. It was Tara now calling from her mobile.

‘Zeena is in the car with me,’ she said quickly. ‘We’re outside her school but she wants to stop off at home first to collect some of her clothes. We should be with you by three o’clock.’

‘All right,’ I said. ‘How is she?’

There was a pause. ‘I’ll tell you when I see you,’ Tara said pointedly.

I replaced the receiver and my unease grew. From Tara’s response I guessed something was wrong. Perhaps Zeena was very upset. Otherwise Tara would have been able to reassure me that Zeena was all right instead of saying, ‘I’ll tell you when I see you.’

My three children were young adults now. Adrian, twenty-two, had returned from university and was working temporarily in a supermarket until he decided what he wanted to do – he was thinking of accountancy. Lucy, my adopted daughter, was nineteen, and was working in a local nursery school. Paula, just eighteen, was in the sixth form at school and had recently taken her A-level examinations. She was hoping to attend university in September. I was divorced; my husband, John, had run off with a younger woman many years previously, and while it had been very hurtful for us all at the time, it was history now. The children (as I still referred to them) wouldn’t be home until later, and I busied myself in the kitchen.

At 2.15 the telephone rang again. ‘We’re leaving Zeena’s home now,’ Tara said tightly. ‘Her mother had her suitcase packed ready. We’ll be with you in about half an hour.’

I thanked her for letting me know and replaced the receiver. I sensed there was trouble in what Tara had left unsaid, and I was surprised Zeena’s mother had packed her daughter’s case so quickly. She couldn’t have known for long that her daughter was going into care – Tara hadn’t known herself for definite until half an hour ago – yet she had spent that time packing. Usually parents are so angry when their child first goes into care (unless they’ve requested help) that they have to be persuaded to part with some of their child’s clothes and personal possessions to help them settle in at their carer’s. I’d have been less surprised if Tara had said there’d been a big scene at Zeena’s home and she wouldn’t be coming into care after all, for teenagers are seldom forced into care against their wishes, even if it is for their own good.

Now assured that Zeena was definitely on her way, I texted Adrian, Paula and Lucy:

Zeena, 14, arriving soon. C u later. Love Mum xx

.

I was looking out of the front-room window when, about half an hour later, a car drew up. I could see the outlines of two women sitting in the front, and then, as the doors opened and they got out, I went into the hall and to the front door to welcome them. The social worker was carrying a battered suitcase.