Storms of My Grandchildren

Read Storms of My Grandchildren Online

Authors: James Hansen

Storms of My Grandchildren

STORMS

OF MY

GRANDCHILDREN

The Truth About the Coming Climate Catastrophe

and Our Last Chance to Save Humanity

JAMES HANSEN

Illustrations by Makiko Sato

New York • Berlin • London

Copyright © 2009 by James Hansen

Illustrations copyright © 2009 by Makiko Sato

All rights reserved. No part of this

book may be used or reproduced in

any manner whatsoever without

written permission from the publisher

except

in the case of brief quotations

embodied in critical articles or

reviews. For information address

Bloomsbury USA, 175 Fifth

Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Published by Bloomsbury USA,

New York

All papers used by Bloomsbury USA are

natural, recyclable products made from

wood grown in well-managed forests. The

manufacturing processes conform to

the environmental regulations of the country

of origin.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

HAS BEEN APPLIED FOR.

eISBN: 978-1-60819-257-1

First U.S. Edition 2009

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Designed by Rachel Reiss

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Worldcolor Fairfield

To Sophie, Connor, Jake,

and all the world’s grandchildren

Contents

APPENDIX 1:

Key Differences with Contrarians

APPENDIX 2:

Global Climate Forcings and Radiative Feedbacks

Planet Earth, creation, the world in which civilization developed, the world with climate patterns that we know and stable shorelines, is in imminent peril. The urgency of the situation crystallized only in the past few years. We now have clear evidence of the crisis, provided by increasingly detailed information about how Earth responded to perturbing forces during its history (very sensitively, with some lag caused by the inertia of massive oceans) and by observations of changes that are beginning to occur around the globe in response to ongoing climate change. The startling conclusion is that continued exploitation of all fossil fuels on Earth threatens not only the other millions of species on the planet but also the survival of humanity itself—and the timetable is shorter than we thought.

How can we be on the precipice of such consequences while local climate change remains small compared with day-to-day weather fluctuations? The urgency derives from the nearness of climate tipping points, beyond which climate dynamics can cause rapid changes out of humanity’s control. Tipping points occur because of amplifying feedbacks—as when a microphone is placed too close to a speaker, which amplifies any little sound picked up by the microphone, which then picks up the amplification, which is again picked up by the speaker, until very quickly the noise becomes unbearable. Climate-related feedbacks include loss of Arctic sea ice, melting ice sheets and glaciers, and release of frozen methane as tundra melts. These and other science matters will be clarified in due course.

There is a social matter that contributes equally to the crisis: government greenwash. I was startled, while plotting data, to see the vast disparity between government words and reality. Greenwashing, expressing concern about global warming and the environment while taking no actions to actually stabilize climate or preserve the environment, is prevalent in the United States and other countries, even those presumed to be the “greenest.”

The tragedy is that the actions needed to stabilize climate, which I will describe, are not only feasible but provide additional benefits as well. How can it be that necessary actions are not taken? It is easy to suggest explanations—the power of special interests on our governments, the short election cycles that diminish concern about long-term consequences—but I will leave that for the reader to assess, based on the facts that I will present.

My role is that of a witness, not a preacher. Writer Robert Pool came to that conclusion when he used those religious metaphors in an article about Steve Schneider (a preacher) and me in the May 11, 1990, issue of

Science

. Pool defined a witness as “someone who believes he has information so important that he cannot keep silent.”

I am aware of claims that I have become a preacher in recent years. That is not correct. Something did change, though. I realized that I am a witness not only to what is happening in our climate system, but also to greenwash. Politicians are happy if scientists provide information and then go away and shut up. But science and policy cannot be divorced. What I’ve seen is that politicians often adopt policies that are merely convenient—but that, using readily available scientific data and empirical information, can be shown to be inconsistent with long-term success.

I believe the biggest obstacle to solving global warming is the role of money in politics, the undue sway of special interests. “But the influence of special interests is impossible to stop,” you say. It had better not be. But the public, and young people in particular, will need to get involved in a major way.

“What?” you say. You already did get involved by working your tail off to help elect President Barack Obama. Sure, I (a registered Independent who has voted for both Republicans and Democrats over the years) voted for change too, and I had moist eyes during his Election Day speech in Chicago. That was and always will be a great day for America. But let me tell you: President Obama does not get it. He and his key advisers are subject to heavy pressures, and so far the approach has been, “Let’s compromise.” So you still have a hell of a lot of work ahead of you. You do not have any choice. Your attitude must be “Yes, we can.”

I am sorry to say that most of what politicians are doing on the climate front is greenwashing—their proposals sound good, but they are deceiving you and themselves at the same time. Politicians think that if matters look difficult, compromise is a good approach. Unfortunately, nature and the laws of physics cannot compromise—they are what they are.

Policy decisions on climate change are being deliberated every day by those without full knowledge of the science, and often with intentional misinformation spawned by special interests. This book was written to help rectify this situation. Citizens with a special interest—in their loved ones—need to become familiar with the science, exercise their democratic rights, and pay attention to politicians’ decisions. Otherwise, it seems, short-term special interests will hold sway in capitals around the world—and we are running out of time.

My approach in this book is to describe my experiences as a scientist interacting with policy makers over the past eight years, beginning on my sixtieth birthday in 2001, the day I spoke to Vice President Dick Cheney and the cabinet-level Climate Task Force. Each chapter discusses a facet of climate science that I hope a nonscientist will find easy to understand. Chapter 1 may be the most challenging. It discusses climate forcing agents—or simply, climate forcings—the subject of my presentation to the Task Force.

The official definition of a climate forcing may seem formidable: “an imposed perturbation of the planet’s energy balance that tends to alter global temperature.” Examples make it easier: If the sun becomes brighter, it is a climate forcing that would tend to make Earth warmer. A human-made change of atmospheric composition is also a climate forcing.

In 2001 I was more sanguine about the climate situation. It seemed that the climate impacts might be tolerable if the atmospheric carbon dioxide amount was kept at a level not exceeding 450 parts per million (ppm; thus 450 ppm is 0.045 percent of the molecules in the air). So far, humans have caused carbon dioxide to increase from 280 ppm in 1750 to 387 ppm in 2009.

During the past few years, however, it has become clear that 387 ppm is already in the dangerous range. It’s crucial that we immediately recognize the need to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide to at most 350 ppm in order to avoid disasters for coming generations. Such a reduction is still practical, but just barely. It requires a prompt phaseout of coal emissions, plus improved forestry and agricultural practices. That part of the story will unfold in later chapters, but we need to acknowledge now that a change of direction is urgent. This is our last chance.

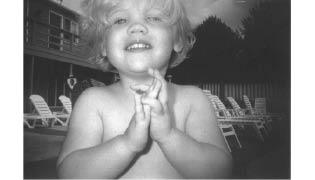

My first grandchild, at almost two years old—changing my perception.

I myself changed over the past eight years, especially after my wife, Anniek, and I had our first grandchildren. At the beginning of this period, I sometimes showed a viewgraph of the photo of our first grandchild on this page during my talks on global warming. At first it was partly a joke, as newspapers were referring to me as the “grandfather of global warming,” and partly pride in a young lady who had become an angel in our lives. But gradually, my perception of being a “witness” changed, leading to a hard decision: I did not want my grandchildren, someday in the future, to look back and say, “Opa understood what was happening, but he did not make it clear.”

That resolve was needed. If it hadn’t been for my grandchildren and my knowledge of what they would face, I would have stayed focused on the pure science, and not persisted in pointing out its relevance to policy. When policy is brought into the discussion, it seems that a lot of forces begin to react. I prefer to just do science. It’s more pleasant, especially when you are having some success in your investigations. If I must serve as a witness, I intend to testify and then get back to the laboratory, where I am comfortable. That is what I intend to do when this book is finished.

BECAUSE THE BOOK opens on my sixtieth birthday, I should mention here a bit about where I came from. I was lucky to be born in a time and place—in Iowa, where I was in high school when Sputnik was launched—that I could be introduced to science in a way that seemed to be normal, yet was very special.

I grew up in western Iowa, one of seven children. My father was a tenant farmer, educated only through the eighth grade, and my parents divorced when I was young. But in those days a public college was not expensive, so it was pretty easy for me to save enough money to go to the University of Iowa.

My career in science, my first step into science research, was born one evening in December 1963. The day before, fellow student Andy Lacis and I had swept leaves, cobwebs, and mice out of a little domed building on a hill in a cornfield just outside Iowa City. The next night, within that dome, an older graduate student, John Zink, helped us use a small telescope to observe a lunar eclipse. When the moon went into eclipse, passing into Earth’s shadow, we were surprised that we saw nothing—just a black area in the sky, without stars, in the spot where we had just seen a full moon; the moon had become invisible to the naked eye. This is not usually the case with an eclipse. Normally, the moon is dimmed but still obvious, because sunlight is refracted by Earth’s atmosphere into the shadow region. However, nine months earlier, in March 1963, there had been a large volcanic eruption, of Mount Agung on the island of Bali, which injected sulfur dioxide gas and dust into Earth’s stratosphere. The sulfur dioxide gas combined with oxygen and water to form a sulfuric acid haze, and the resulting particles in the stratosphere blocked most of the sunlight that normally is refracted into Earth’s shadow.

We measured the brightness of the moon with a photometer attached to the telescope, and in the next year I was able to figure out how much material there must have been in Earth’s stratosphere to make the moon as dark as it was. Mainly that required reading some papers (in German) written by the Czechoslovakian astronomer František Link, who had worked out the equations for the eclipse geometry, and writing a computer program for the calculations. The result was my first scientific paper, published in the

Journal of Geophysical Research

—my first experience as a witness, at least a witness of science, if not in the biblical sense.

Our good fortune was that we had found our way into the Physics and Astronomy Department of a remarkable man, James Van Allen. An astronomy professor in Van Allen’s department, noticing that Andy and I were capable students, convinced us to take the physics graduate school qualifying examinations in our senior year. We were the first undergraduates to pass that exam, and, perhaps as a result, we both were offered NASA graduate traineeships, which fully covered our costs to attend graduate school.

I was so shy and uncertain of my abilities that I had avoided taking any of Professor Van Allen’s classes, not wanting to reveal my ignorance. But Van Allen noticed me anyhow—probably because I had not only passed the graduate exam but also received one of the higher scores. He told me about recent observational data concerning the planet Venus, which suggested that either the surface of Venus must be very hot or the planet had a highly charged ionosphere emitting microwave radiation. When I started to work on the Venus data for a Ph.D. thesis, Van Allen appointed himself as chairman of my thesis committee. If it had not been for the attentiveness and generosity of this soft-spoken, gentle man, whom no student ever should have been intimidated by, I probably would not have gotten involved in planetary studies.

More than a decade later, in 1978, I was still studying Venus. And by then I was responsible for an experiment that was on its way to that planet, aboard the Pioneer Venus mission. In the five years since I had proposed that experiment to measure the properties of the Venus clouds, I had been working about eighty hours per week. Anniek, whom I had met while I was on a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands, continued to believe me, each year, when I said that the next year I would have more time. Then I had to tell her that, after all that effort, I was going to resign from the Pioneer mission before it arrived at Venus, turning the experiment over to Larry Travis, another friend and colleague from Iowa.

The reason: The composition of the atmosphere of our home planet was changing before our eyes, and it was changing more and more rapidly. Surely that would affect Earth’s climate. The most important change was the level of carbon dioxide, which was being added to the air by the burning of fossil fuels. We knew that carbon dioxide determined the climate on Mars and Venus. I decided it would be more useful and interesting to try to help understand how the climate on our own planet would change, rather than study the veil of clouds shrouding Venus. Building a computer model for Earth’s climate was also going to be a lot more work. As always, Anniek accepted, and tried to believe, my promise that it would be a temporary obsession.